Pilgrimage

by Barendina Smedley

“You argue by results, as this world does

To settle if an act be good or bad.”

TS Eliot, Murder in the Cathedral (1935)

For three nights in a row, Agnes dreamed the same dream.

On the morning after that third night, she washed her face, put on her best red damask gown, fresh linen and also a hood in the new fashion, and went to see the parson.

Sir John rarely visited the village, a wealthy little port on the Norfolk coast. His other livings — there were perhaps half a dozen of these now — were all better situated — closer to the places frequented by mighty men and their wives. Nevertheless, he happened to be in residence at the moment, dealing with a lawsuit, an unreliable bailiff and contested tithes. So it was that Agnes found him there in the parsonage, enthroned at the high end of the hall, holding court as members of his flock, more or less welcome, offered up to him and his secretary their complaints, petitions and grievances.

The parson’s eyes lit up when he noticed Agnes at the far end of the room. Somehow the crowd of people — friends, neighbours, relations — parted before her, so that within a few moments she was standing in front of the parson, who looked her up and down, rose, and, almost before she knew it, had shepherded her into the parlour beyond.

“Ah, Mistress Wright, we must speak about that husband of yours, and the roof of this, my poor parsonage house, and why it lets in the rain!” he declaimed, loudly, as he shut the door, for the benefit of those waiting outside.

The two stood alone for a moment, regarding one another. Each thought the other had aged a little. This was, of course, true. All the same, there was a kind of agreement between them, even a sort of familiar warmth, which they enjoyed in silence for a moment.

“Why are you here, Agnes? I trust Valentine keeps well?”

“Oh yes, the fits have passed entirely these last few months. I think Hubert sent you word of him? Valentine is like any other six-year old child now, God be praised.”

“God be praised,” agreed the parson, his dark eyes shining, unable to look away from the woman who stood before him.

“And that is why I must go to St Thomas, the blessed martyr, to give him thanks.”

Here the parson sighed, laughed mirthlessly, shook his head, and started to pace around the room.

“You are a foolish headstrong woman, Agnes. If you want to thank St Thomas, why not thank him here? Your husband is an officer of St Thomas’ own altar gild, here in this parish, for heaven’s sake! Also, why are you so certain it’s St Thomas you should thank? Why not Withburga or Walstan? Or Felix? Or Our Lady of Walsingham, as far as that goes — although if you wish to bother her yet again, I’d advise you, in all confidence, to do so sooner rather than later?

“No, Agnes, you’ve troubled every saint between here and the German Ocean and some besides with Valentine and his business. I have no time for a theology lecture this morning, my sweetheart, my darling, but you also know very well that the grace that healed Valentine — assuming that it was Becket that healed him, which seems debatable to me — flows ultimately from our Lord. You really needn’t travel all the way down to Canterbury — unless you simply want a holiday from Master Wright, which I could well imagine.

“Speaking of which, send him to me, won’t you? I wasn’t entirely in jest when I spoke at the door. The roof over the curate’s room is letting in water every time it rains here. He complains of it endlessly. They are very wearisome to me, the curate’s eloquent, unanswerable complaints. And the floor in the buttery is always wet.”

Agnes simply looked at the parson, who eventually stopped pacing about.

“Agnes, my dearest, my heart, don’t go to Canterbury. Not now.”

“I must go.” Calmly, she told the parson about the dream.

“Oh, very well then. I suppose you want some money for the journey?”

“No, I need no money, thank you,” she replied. “My husband has enough. We’ve done well these past few years. God has been merciful to us. I am only here to seek your blessing.”

“And what will you do about Valentine while you are away?” the parson asked. “Will you leave him with your sister?”

“No, I will take him with me,” Agnes replied. “He must thank St Thomas too! He’s well enough now. Valentine and I will go together.”

So the parson, formally and in Latin — although they were already in a season when Latin prayers had fallen out of favour — offered Agnes his blessing. Then, as she had known he would, rather gently at first — later rather less so — he folded her into his arms and began to kiss her.

Sir John smelled of oranges and cloves, civet and vetiver. The marten fur of his robe was very soft.

* * *

It was near the end of August, on a late summer day so hot that the air shimmered like water, when Agnes finally set off on her pilgrimage. Her husband had insisted that she travel with three servants — her maid, her husband’s foreman Hubert and his boy — and so, with Valentine, they made up a little party of five.

Hubert was one of life’s pessimists, predicting with bleak relish that they would all be set upon, robbed and left for dead before they got as far as Swaffham, let alone Saffron Walden. Jane, Agnes’ maid, had never been further away than Holt in her entire fifteen years — and Holt was only an hour’s walk from Blakeney haven. As for Hubert’s boy, he was one of those country boys who rarely say anything. Valentine, though, who in some ways resembled his father, sat confidently on his mule, rode very well, and positively beamed with pleasure. He was glad to be going to Canterbury.

It took them five days, all told, to reach London. Still, the weather remained baking hot. Agnes rode covered, and tried to make Valentine do the same, but most of the others were soon burned red from the sun.

Once the had arrived at London, Hubert had some business to transact on behalf of Mr Wright. After he had issued them with an apparently endless series of warnings and dire prognostications, Agnes and the rest of the party were able to explore the city.

Although young Jane, the maid, would gladly have spent the whole day pondering the riches of Cheapside, where it was possible to purchase everything she had ever imagined and quite a lot more besides, and Valentine was happy enough staring bright-eyed at the passing crowds, Agnes had her own, more demanding scheme. As was usual, it was Agnes’ way that prevailed.

So it was, then, that instead of shopping for ribbons or gazing at strangers, the party first visited the Mercers’ Hall, which for reasons no one could quite explain, occupied the site of St Thomas’ birthplace. Then they moved on to the place where St Thomas’ parents were buried, and his chapel on London Bridge, before making their way back, somewhat circuitously, towards the vast bulk of St Paul’s cathedral. Here, Agnes had hoped to find a famous image of St Thomas before one of the many altars. In the event, though, the image had gone, so she made her prayers to St Thomas without it.

A few passers-by saw what she was doing, and crossed themselves. If others shook their heads, or worse, Agnes took no notice.

To anyone who would listen, Agnes insisted on recounting, politely but insistently, the basic components of Valentine’s story. She also purchased a very large candle, to be offered to St Thomas when they finally arrived at his shrine, and entrusted this to Hubert’s rather reluctant care.

When Hubert’s boy saw how much money Agnes dispensed at each of these places, and how devoutly she prayed, he was even more markedly silent than usual. Truly, in his whole young life he had never seen anything so remarkable.

At Southwark, which was on the other side of the very wide river, the party soon found themselves in the company of a small group of other pilgrims. Jane and Hubert’s boy were fascinated, never having met so many strange and various people all at one time. Valentine, who despite his youth was rather more worldly, regarded them all with cheerful curiosity.

Hubert, for his part, said something, only just sotto voce and to no one in particular, along the lines that “there must be a fair few villages missing their idiot today”.

For indeed, alongside a few of the better sort — a learned and sad-faced friar, a lawyer troubled in his mind, an old lady from the West Country who had been cured of dropsy, although not, it appeared, of a tremor, deafness or confusion — there were the other sort of pilgrims, too. These were sexless creatures, brown from the sun and the road and gratuitous hardship, some lacking limbs, their ragged clothes and broad-brimmed hats studded with the medals of every shrine imaginable, in England but also beyond the seas — people who begged for alms but only laughed a toothless laugh if you turned them away, whose feet were like animals’ thick pads, people who went from pilgrimage on to pilgrimage without ever going home in between.

Of course Agnes gave these other pilgrims money, too, until Hubert stopped her — at which point she simply gave them money secretly, when she thought, often incorrectly, that Hubert wasn’t looking.

* * *

The journey from Southwark down to Canterbury took another six days. It would have been far less, as Hubert noted repeatedly, if it hadn’t been for the strict penance involved in travelling alongside those other “blessed” (Hubert might have used a different word) pilgrims.

The old lady from the West Country who had been cured of dropsy rode badly — amongst her other troubles, she was possibly slightly blind. In the end, the only solution was for her to take Valentine’s donkey. This, in turn, meant that Valentine presided happily over Hubert’s boy’s gelding, leaving Hubert’s boy, mutely uncomplaining as ever, to walk alongside them.

The friar, meanwhile, was convulsed with a hollow cough. He shivered in the hot sunshine, sweated at night, and fainted at inconvenient moments. The lawyer was distracted in his wits. He kept leaving things behind and then having to go back for them while the rest of the party waited somewhere in the shade, tired yet also restless. Sometimes it turned out that the things for which the lawyer sought hadn’t really existed in the first place.

As for the professional pilgrims, none of this surprised them. They sat on the ground, warming their faces in the sun, begging alms from passers-by, play-fighting with their palmers’ staves, passing the time by making coarse jokes with one another, picking absently at their various sores.

While Hubert had quite a lot to say about these developments — not all of it couched in particularly pious language — and Valentine, who like his father took an easy, uncomplicated joy in things — as they made their way along the edge of the Downs, eking out the last days of that summer’s hot sun, Agnes seemed increasingly to withdraw into a world of her own.

Of course she was still more than ready to loan the old lady her second-best linen veil, cloak, to offer the friar fruit comfits from the little silk bag she always carried with her, or to comfort the lawyer by pretending that she, too, remembered the beautifully-illustrated printed primer he believed he had left behind at Southwark.

She didn’t seem to mind, however, when Valentine somehow wandered off on his own when they were all at Wrotham — he had, as he told the professional pilgrim who eventually reclaimed him, simply been speaking with some fairies he had met on the way — or when another group of pilgrims, returning from Canterbury, reported discouragingly that the city was full of the King’s men, “so that St Thomas is not thought likely to tarry there much longer”.

Nothing troubled Agnes. She would turn her lovely, imperious face to the sun as she rode, her eyes closed, a sort of dreamy ecstasy playing about her fine features, as if in her heart she were at Canterbury already.

“Watch where you go, Mistress Wright!” Hubert warned her, one afternoon as they were riding along the well-worn old road that passes near Rochester.

“St Thomas knows where I’m going, Hubert” she replied equitably, opening her eyes again, turning and looking squarely at him. “Can you really not feel him here with us?”

“If you don’t mind, I’ll leave the apprehending of saints to you, Mistress Wright,” said Hubert. “I’ve got my hands full with this lot, who — and I’m only guessing here — might not all be saints.” He indicated, with a toss of his head, the disreputable little band of professional pilgrims drifting along in their wake. “And, while we’re at it, I’ve got my hands full with the robbers, thieves, footpads, sundry assorted villains — and the thunderstorms! There are sure to be thunderstorms soon. And the stones and ruts and suchlike on this road. And serpents and vipers. And mad dogs, too.

“Also, I ain’t exactly enamoured of what those nere-do-wells said last night about the King’s men, neither. You heard the news from Walsingham, same as I did —”

“Yes, Master Wright told me. He had a big contract lined up with the prior there, but in the end they had to cancel it. He was most disappointed.”

“You know what I mean, and it ain’t that. Well, what if, when we finally reach this Canterbury of yours — assuming, of course, that no one slits our throats on the way, which is more than I’d assume — and this St Thomas of your has long departed? What if the King and his commissioners have turfed Becket out of his fancy box and thrown him onto a bonfire? You know what happened at Walsingham — how they tore the whole lot down, in only a matter of days. If they’re playing the same tune at Canterbury, we’d have come all this long way, wasted so much time, spent so much money for — well, for what?”

“St Thomas won’t let that happen, Hubert,” replied Agnes evenly, re-adjusting her veil slightly, the dreamy half-smile still playing across her face. “As I’m sure I told you just a moment ago, he’s with us, God be praised! With St Thomas’ help, there is nothing we cannot do. Think of all the miracles that St Thomas had managed over so many years, Hubert — so many centuries. With St Thomas on our side, who can hinder us?”

Hubert grimaced. “Some do say — and don’t you go getting angry with me, Mistress Wright, because your old Hubert here is only repeating what other folk tell him — some do say that the things you call the miracles of St Thomas, are only made-up miracles.”

“How ridiculous!” exclaimed Agnes. “What a remarkably silly thing to say, Hubert! St Thomas’ miracles are written down in history, by exactly the same learned men who wrote saints’ lives and chronicles and evidences, just like anything else. Or are you to tell me that all of history is made up, too?”

“I’m telling you no such thing, as well you know. I’m only telling you what some do say, including plenty of solid, sensible folk — the more so, these last few years. That’s what worries me. Plenty of folk say that all the things you call ‘miracles’ are just tricks, old Popish baggage, cheap foolish mummery to dazzle silly women — all just to make money for those that keep the shrines! Why, even that parson of yours said as much before we set off, in that long sermon of his, with all the village listening to him, too —”

Agnes coloured suddenly, although whether that was due to the heat of the afternoon, or some other cause entirely, we may all form our own judgement. Certainly, though, whatever it was, her voice, when she finally replied, had an edge to it.

“In the first place, Hubert, Sir John Clayton, our parson, for the respect we all bear him — considerable though that must necessarily be, under the circumstances — is a man. Which means that, as all men do, he sometimes speaks nonsense.

“Secondly, though, and more to the point — Hubert, surely you know that our Saviour healed the lame and the blind, caused Lazarus to rise from the dead, made water into wine —”

“Now that’s a miracle I wouldn’t mind seeing done,” opined Hubert.

“ — Our Saviour fed multitudes, walked on the surface of the water, overfilled the fishermen’s nets and suchlike, about all of which we have ample, certain and undoubted testimony in the Gospels?”

“That,” replied Hubert, “is for others to say.”

“And when our blessed Saviour was hung on the tree, laid in the tomb, then after three days he rose from the dead, and many who had known him recognised him, and testified to the truth of it afterwards — well, surely that was a miracle?”

“You know I’m no doctor of the church, nor a scholar neither!” protested Hubert, increasingly sulky. “I’m a master builder’s foreman. Ask me about timber instead. I know a lot about timber.”

“Hubert, after our Saviour rose from the dead, is it not similarly a well-attested thing that his Apostles were able to heal, too, just as our Saviour had done before? Were those not miracles? And, if so, why should the miracles stop there? Why shouldn’t they carry on? Or do you” — and here Agnes assumed a slightly mocking tone — “do you imagine that our Lord required an end to miracles at such a day and time, as if set out in some sort of lease or builders’ contract? Or that the Holy Ghost can’t work perfectly well through a man or a piece of timber if that’s what God ordains?”

“I can tell you all about timber, Mistress Wright,” Hubert replied, sharply. “Any kind of timber you like. Oak, elm, walnut, even Baltic pine. Just timber, not miracles alongside timber. Will that not do? Please, lady, save the disputations for someone else! I’m a master builder’s foreman. I’m here because Master Wright made me promise in the name of all that’s holy to see you safely to Canterbury and back again — you and Valentine both. It’s Master Wright I’m here to serve — no one else, saint nor otherwise. I don’t need to know no more than that.” He paused for a few seconds. His face, too, was flushed now. “The sun is devilish hot this afternoon, ain’t it?”

Agnes sat back a little in her saddle, her mouth fixed into a hard smile. She was not a woman who gave up easily, though, so she tried one more time.

“St Thomas healed Valentine, Hubert! That’s all there is to say about it. I don’t know why you’re making such heavy weather of this. Valentine’s cure was a miracle, and that miracle was worked through St Thomas of Canterbury. I know it’s the fashion of the moment to scorn the old ways — everything our parents taught us, and their parents before them, too — but it’s a fashion that will pass, just like all the others. And in the meantime, St Thomas will look after us, God be praised! Trust him, as I do.”

Ahead of them, the path dipped down, sharply, into a pleasant little valley. Its charms were set out neatly and honestly before them, as if trying to persuade generations of doubtful passers-by of its merit — the silver brook, fringed with willows, snaking through a green meadow; a few little houses dotted here and there with the neat yards and gardens around them; woodsmoke hanging in the air; a little copse of trees, gilded in the late afternoon sunshine by the very first hint of autumn. In the village that lay beyond they would, probably, find an inn for the night.

Behind them, they could hear Jane, Agnes’ maid, laughing with the best-looking and cleanest of the professional pilgrims. Hubert’s boy, who loved Jane, was storming ahead, seething with silent fury. Little Valentine, meanwhile, was regaling the sad friar, confidently if with a degree of poetic license, with everything he knew about Norfolk. His clear, high, trilling voice rang out across the curves and folds of the countryside.

These things had, in recent days, all become familiar. It was odd to think that there would come a point when the journey was done, that it wouldn’t simply go on forever.

Hubert considered, in those endless moments, whether to hold his peace. Almost certainly, that would have been the better course. In the end, though, because in truth he was no better than anyone else in this tale, he couldn’t quite manage it.

He spoke hesitantly. “Don’t think I don’t understand what you say. Most likely you’re right. You generally are. And it makes me uneasy, too, seeing so much change in such a very little time. Still, might it not be the case, Mistress Wright” — and here his tone turned surprisingly gentle, almost as if he were speaking with Valentine — “that once there was a season for miracles, such as are written down in books or told in stories, but now that season has passed? Don’t it happen, sometimes, that one season ends and another begins? Isn’t that a true thing, too, that we know from our own lives?”

Agnes and Hubert rode alongside each other, entirely silent, for what seemed to them both an awkwardly long time.

* * *

Canterbury, when they reached it, was all that the party had dreamed it would be.

Glimpsed at first from afar, its tall towers and spires had all the strange potency of a vision, pulling them along with a kind of inevitability. As they drew nearer, jostling with increasing amounts of other traffic along the dusty and rutted road, even Hubert had to admit to being impressed. “It ain’t such a bad place, Canterbury,” he conceded. “It’s not Norfolk, mind you, but all the same, I’ve seen worse.”

The air in Canterbury was soft — much more so than in Norfolk — and the streets were very wide. There was a great stone wall around the city, as in Norwich, and handsome proud gates.

“You’re a lucky lad,” one of the watchmen said to Valentine as he and Agnes passed them. “If you’re quick about it, you might see His Majesty the King. He’s here at the moment.”

“We have come to see St Thomas,” replied Agnes briskly, and rode on.

It turned out that the King was indeed in Canterbury, possibly accompanied by the Lord Chancellor. He was installed at St Augustine’s Abbey, in the abbot’s lodgings.

They heard the whole story later that afternoon. It was only about a month, apparently, since the abbot had surrendered the whole establishment to the crown — since he had left it, along with all the monks from that foundation. St Augustine’s Abbey had been a monastic house for nearly a thousand years. Now, although the monks of Christ Church were still — for the moment — unaffected, everywhere one looked, there were tonsured men, a few of them now in ordinary laymen’s clothing, standing in the shadows, looking aimless and unhappy.

“Funny old times, these,” said Hubert, to which there was no very obvious reply.

“You’re cuttin’ it a bit fine, aren’t you?” asked the innkeeper. “King’s commissioners are in town again, and that don’t never mean nothin’ good.”

“Should we go to Christ Church now?” asked Agnes. For the first time and perhaps the only time during that whole long journey, she felt a twinge of doubt. What a pity it would be to have come so far, only for everything to fall apart at the last moment!

But Hubert wanted his dinner, Jane was out of sorts from the sun and the journey, Valentine looked tired after riding for much of the day — and Hubert’s boy had something wrong with his foot, and was limping, which one of the professional pilgrim found funny. Also, Agnes remembered her faith once again.

She suggested, in her usual forcefuly way, that Hubert’s boy should seek St Thomas’ help.

“I reckon St Thomas has enough problems of his own to deal with,” said Hubert. “And I also reckon that St Thomas can manage without us until tomorrow morning. Here, Master Valentine, let’s get you something to drink.”

* * *

Over the course of the journey, the professional pilgrims, many of whom had been to Canterbury at least once before, had told Agnes what to expect.

In the summer, they had told her, the shrine opened soon after 5 in the morning. The moment was marked by the tolling of Great Thomas, the oldest and loudest of the Christ Church bells. Then, before anything else happened, there was a solemn Mass of St Thomas said at the altar of the Trinity Chapel. This, deep in the heart of the cathedral, was where St Thomas himself rested. The martyr’s bones were enshrined in a stupendously costly casket, wrought from purest gold and studded with all sorts of precious stones, including a ruby called the Regale, once given by the king of France, as large as a duck’s egg.

At this point, the pilgrim who was telling the story invariably mimed with his hands how big a duck’s egg actually was, in case Agnes and anyone else who was listening might not fully grasp the significance of this claim.

After Mass one could, if one wished, visit the many other sites within the cathedral associated with Thomas of Canterbury’s life, grisly martyrdom and glorious sainthood, led on this potentially long and labyrinthine journey by one of the designated shrine guardians — monks from the priory — two of who were on duty each day.

Here, one might be shown the altar at which St Thomas had been hacked to death by King Henry’s men, the tomb in the crypt where he had first been buried, or a large cabinet full of miscellaneous yet spectacular relics, more or less numinous, associated with a great variety of other saints. At the Corona Chapel one might — especially if one brought along a generous offering with which to thank the guardians of the Shrine — be allowed to kiss the round, biscuit-brown, wafer-like portion of the saint’s own skull lopped off by the King’s men, later rescued from the blood-smeared floor and encased in its own silver reliquary.

The high point of the visit, though, was the encounter with the saint’s own shrine — although this, again, was generally reserved for what the professional pilgrim telling the story unselfconsciously titled “folk like you, lady”. Ordinary pilgrims had to make do with glimpses through various iron screens or across the surface of ancient tombs. It was blessing enough, though, to be able to draw so near to St Thomas, England’s greatest saint, whose name was known across Christendom and beyond.

Later, perhaps, one could acquire, in return for appropriate alms, a pilgrimage badge, or a lead phial of water in which was dissolved some vanishingly tiny yet miraculously efficacious measure of the martyr’s own wonder-working blood. Proudly, the pilgrims showed off examples they themselves carried. Agnes had listened, patiently handled and admired each item, all with genuine devotion. Cynical though they were, as a group, the pilgrims rather loved her for this.

But as they all waited outside the main gates of Christ Church very early on that pale September morning — although the day had dawned fair, the air was surprisingly cool, almost as if autumn had arrived overnight — no bell tolled. Agnes noticed that only a handful of pilgrims were there, almost all of them from their own party.

Eventually a tired-looking monk appeared, hauling the great gates open. He looked surprised to see them.

“Did no one tell you? The commissioners are here today,” he said. “I can’t imagine they’ll be letting anyone in, today of all days.”

“Sir, we have come all the way from Norfolk,” said Agnes. “St Thomas healed my son Valentine. Valentine used to have fits, and now he doesn’t. You must let me thank St Thomas. Look, we have brought the saint a candle.”

Agnes indicated the large wax candle that Hubert was carrying. It was fully as tall as Valentine himself — and Valentine was quite tall for his age.

The tired-looking monk regarded the candle with a sort of weary despair. “Yes, it’s a very admirable candle,” he said, “and under normal circumstances St Thomas would be thrilled, I am sure, to have it. We all would. But the saint really isn’t welcoming any pilgrims today. I’m so sorry.” And he made as if the shut the gate again.

Agnes, before Hubert could stop her, flung herself into the narrowing gap so that the monk was forced to pause, while the other pilgrims looked on with various degrees of fascination.

“Really, sir, with the greatest respect, you don’t understand,” she said. “St Thomas appeared to me in a dream. He appeared for three nights in a row. And he told me that I must come here, to Canterbury, with Valentine, and thank him for what he has done. Surely you must let me in?”

The tired monk regarded them all — this strange little party — Mistress Agnes who even now still clung on to the remnants of her largely unselfconscious beauty, glaring stout Hubert, bright-eyed Valentine — and of course the lawyer, the lady from the West Country, the tonsured friar and all the rest, a few of whom he was almost sure he knew by sight.

“Oh, all right then — but if anyone asks you, it wasn’t I that let you in, yes?”

Agnes rewarded him with a glowing smile and a stealthily-managed tip. The monk, despite being a genuinely conscientious and pious soul, simply pocketed the coin. What was the point, after all, today of all days, in consigning it to the priory’s coffers?

* * *

Once inside the huge precinct gates, Valentine paused to admire the scene before him. For indeed, Christ Church itself — Canterbury cathedral — was spectacular.

Valentine, despite his tender years, was no innocent country boy. In her efforts to cure him, his mother had taken him to every shrine within easy striking distance of his north Norfolk home. Thus it was that he had seen the priory at Walsingham many times before, that he had travelled to Norwich, that he knew Bromholm and Crowland and Bury St Edmunds and many other famous places besides. But never before had he seen a church that struck him quite as this one did. Vast, sand-coloured, rambling and complicated, its form and majesty reminded him of some huge ship’s hull studded with barnacles, of his father’s best mastiff bitch surrounded by her lively, questing pups, or indeed those visions of the Holy City itself that, even now, sometimes still came to him when he least expected them.

Once he was inside, however, the building seemed to him more like a forest, although a forest seen in a dream — or perhaps a forest not of this world.

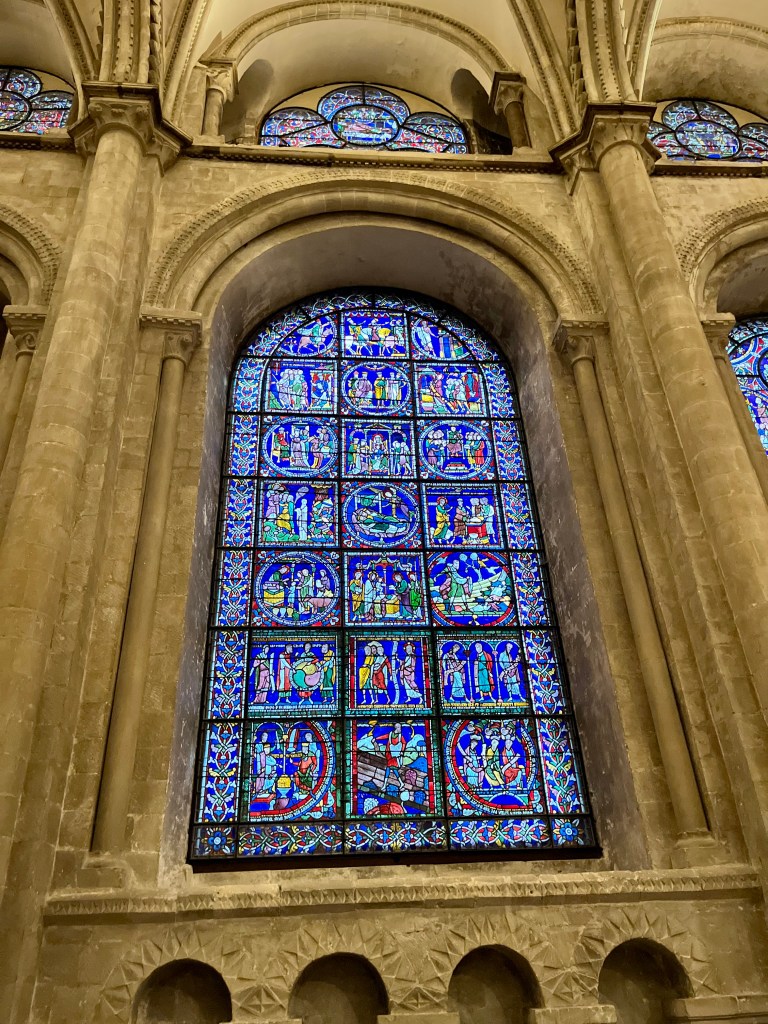

The light that shone through the windows was like nothing Valentine had experienced before. While the adults argued, he occupied himself in trying to fix it in his mind — not just the stories set out in the glass, their profusion and splendour, but that unfathomable azure blue in particular. Decades later, remembering that day, it was the luminous, coruscating, almost supernaturally brilliant blue that stayed with him more than anything else — except, perhaps, the grip of his mother’s hand on his own, which somehow became intertwined with the memory of the high whitewashed walls and sharp-toothed vaults, the incense-tinged air of those cold stony spaces — together, a little later, with the sharp, almost painful pang of proximate sanctity.

If, when he was very old, anyone had thought to ask Valentine what exists beyond this world — although, as far as I know, the question was never posed to him in just such a way — the answer would have contained all these things, experienced once, long ago, over a few minutes only — unrecoverable, by then, but never entirely forgotten.

* * *

Well, that is as it may be. Once inside the precinct gates, the next challenge was to gain entry to the actual cathedral.

While Mistress Wright plunged ahead towards the great southwest porch, almost dragging Valentine along with her — with Hubert, cradling the child-sized candle in his arms, struggling to keep up — Jane, Mistress Wright’s girl, allowed herself to fall back a little.

Where was Leo? In a moment, though, he appeared by her side, flashing in her direction a quick, secret, slightly antic smile that made her blush, and turn away again, nervously pushing a stray lock of hair back under the edge of her coif.

Leo was tall, handsome, mercurial — impossible. Life on the road had burned his skin brown as a hazelnut, but his hair was so blond as to be almost white, and his eyes were blue as the cornflowers that were still, even long after the harvest, blooming in the field margins. He spoke not the decent, godly language that was spoken in north Norfolk, but rather some other thing, also learned on the road — a salmagundi of German, Dutch and Romany, spiced here and there with French, Spanish, only finally garnished with the tiniest twist of English.

Jane and Leo, though, did not speak much when they were together.

Leo’s leather jerkin, as brown as he was, had attached to it with ribands a good two dozen pilgrimage badges. Although he was young, he had been on the road for years. No one knew how long he had been on the road. Leo was good at begging for alms, but also good at stealing — and other things besides. Jane blushed again. That was the main point, though — Leo was impossible.

Hubert’s boy, meanwhile, had found them again. He, too, now, stood next to Jane. Sandy-haired, shy, decent, tender-hearted, implacable, he hated Leo more than he had ever hated anyone or anything in his life. Conversely, his love for Jane was so vast, so insistent and all-consuming, that it seemed to block out everything else in the universe. He would have done anything for her. He would gladly, in that moment, have died for her, if he could.

As that particular circumstance, however, didn’t immediately arise, he simply stood next to her, half-apologetic, half-insistent, simultaneously understanding the contempt that she felt for him — which, incidentally, he regarded as perfectly reasonable — yet also doggedly certain that the two of them were, somehow, destined to be linked together for all eternity.

Mistress Wright, they could see, was remonstrating, politely but firmly, with yet another group of important-looking, stubborn, angry men. She was dressed, that day, in her very best damask gown. Jane had helped her dress that morning. The gown was blood red — the colour of martyrdom. With her hood in the new fashion, her gold necklace and brooch, she cut an elegant figure — every inch the wife of one of the richest master carpenters in one of the richest villages of the faraway north Norfolk coast. They all felt obscurely proud, in their various ways, of their association with her.

Jane was wearing her usual gown of tawny worsted — her only gown. Inside her bodice, though, where no one could see it, hung on a bit of a string, was the thin silver ring that Leo had given her. The ring was, she knew, probably stolen. She didn’t care.

She was also, that day, by the way, carrying with her another secret, although she hardly liked to admit it even to herself, at least in that company, or in such a holy place. Unthinkingly, she crossed herself. Leo didn’t notice.

“Sir John Clayton gave me his blessing” … “I dreamed it three times” … “really, how ridiculous you are!”

The three young people could hear the familiar phrases and imagine the rest, even as they watched from a distance, seeing Hubert shifting the heavy candle from one shoulder to the other, Valentine fidgeting slightly and turning his face up to look at the sky, Agnes gesturing towards the great door in front of them. Quite a few large wagons were drawn up near the porch, empty, as if waiting to be filled with something, but it didn’t occur to Jane to wonder about this.

Jane had never been out of Norfolk before. Rather shamefully, she had never been further than Holt, the nearest market town, and she hadn’t been there very often either.

Jane had known Hubert’s boy since they were both children — their mothers were cousins of some sort, possibly their fathers too. As children they had played and argued and fought with each other. Hubert’s boy was as familiar to her as any familiar thing — the worn straw mattress in Mistress Wright’s little chamber where she and the other girl slept, the smell of wood-smoke and dogs and human bodies, the wind from the north in winter, the brackish tang of the saltmarsh, the creaking sound that the masted ships in the harbour made when they rode at anchor. When she tried to think of him, he was so familiar that she could, in fact, form no image of him whatsoever in her mind.

Unconsciously, she turned to look at him and, by accident, met his mild eyes. She looked away again. He continued to stare at her, not caring that Leo, offensive as ever, was laughing at him for doing so.

Something was happening now just inside the great southwest porch of the cathedral. Mistress Wright pushed forward, shoving Valentine in through the door ahead of her. Hubert, too, barged his way in, his broad shoulders braced for a moment in the door, obviously much to the annoyance of the great personages who were trying to prevent him from entering. Then, however, with a sharp report, the door banged shut again.

“Bar the doors! Bar the doors!”

A commotion followed, with much shouting and rushing about on the part of the laymen in particular.

“None of you lot are setting foot in this church today,” barked the man who was standing by the door where Agnes and her party had just entered, seeing the pilgrims. “I don’t care how far you’ve come, what you dream about at night, nor how famous your parson is. Go away! Go home! There aren’t to be any more pilgrims here. None. Did you hear that? Not a single pilgrim more. Go away! Go home! Read your Bibles in English like decent Christian folk do! Mind the Ten Commandments! Stop gadding about the countryside whoring after false idols!” He paused a moment, seeking an appropriate summation. Then, very loudly indeed, “God save the King!”

An unhappy, wordless yet somehow resigned sort of sound rose from the multitude outside. Jane, unsure what to do, glanced around her.

The sad friar had fallen to the ground and was weeping inconsolably. The lawyer, looking confused, had taken the arm of the old lady from the West Country and was supporting her, explaining as much to himself as to anyone else that the man at the door could not possibly do what he had just done.

The professional pilgrims, on the other hand, treated this reverse of fortune much as they did any other change in the weather. Which is to say, many of them knew that free food was, traditionally, offered to pilgrims by priory brethren, so they went off to discover whether that old custom, at least, still held good. A few prayed aloud, there where they stood, without self-consciousness or doubt, as much from habit as anything else — which is a good way to pray. Others simply sat by the wall, there inside the precinct, and warmed themselves in the sunshine. For the moment, at least, they didn’t have to go anywhere at all.

For Jane, though, the shutting of the door hardly registered. She had never doubted — none of them had, really — that Mistress Wright would, in the end, have her way. Nor did she mind too much about failing to enter the cathedral, as this was an honour of which, without any false modesty, she felt herself unworthy. No, Jane would simply wait for Mistress Wright and her party to emerge, after a more or less lengthy interval, from the great building before them. That was the situation.

Jane refused to think beyond that point, about what might happen afterwards.

Leo, meanwhile —understanding very well what the man at the door had said, but also appreciating the opportunities presented by a crowd increasingly composed of relatively wealthy and well-dressed people — had vanished into the throng that was, for some reason, growing steadily inside the precinct.

Leo, alas, was bereft of conscience. He was a creature of pure appetite. Something was missing in him. Morality did not enter into what passed for his calculations. Still, despite all this, he, too, understood that Jane was impossible.

In his case, however, this was simply a matter of expediency. For the past few days, Jane had proved an entertaining challenge. She was pretty, although unremarkably so. He found her nice, fastidious ways mildly amusing. She would, though, make a poor sort of companion on the road. She was too much like her mistress, Leo thought to himself — demanding, slightly spoilt, blandly convinced that her way of doing things was invariably the correct one. What could one do, on the road, with that?

No, Jane would be a check on his enterprises, his impulses, the sheer variety of experiences that, insofar as he was capable of love, he loved more than anything else. Novelty had the force of religion for him. So as soon as he had lightened a few pockets, he managed to slip away — out of the precinct gates, then later, out of the city itself. There were still pilgrimages to be had in France, Spain, Italy — perhaps even Jerusalem. After that, Jane never troubled Leo’s mind again.

As for Hubert’s boy, when the door to the cathedral slammed shut, he simply stayed where he was, mute, motionless, staring into the middle distance.

This time, though, it was different. In those last few minutes, something had shifted, profoundly, within him. In his silence he was, more urgently than he had ever before done, praying — praying to St Thomas, or anyone who would listen — praying the kind of prayer that is, by reason of its sheer urgency, necessarily wordless.

* * *

“No, there will be no Mass of St Thomas today.”

The man who stood before them, barring their way, was neither monk nor secular priest. He was a layman. He must have been about forty summers old. His clothes were fine — expensive, all of the latest fashion, from his marten collar to his silk doublet — yet his bearing had something thuggish about it. His hat was firmly set on his head. His broad, flushed, stupid face bore the air of belligerence seeking a purpose. He wasn’t yet sneering at Agnes, at least not obviously so. All the same time, there was something about him to which Hubert, in particular, took an instant dislike.

Agnes simply gazed at the man. As with most of the problems that had beset her over the years, the challenge here was a simple one. She knew what she meant to do. She could see that that very well. All that was required, now, was to understand how to do it. She had no doubt in her mind, not the least, that she would achieve her ends.

“Very well, sir,” she said to the man. “There will be no Mass, just as there was a man who barred our way at the door, and prevented our friends from completing their pilgrimage. There will be no Mass, just as there are no guardians of the shrine or other learned folk lingering here, to show us the holy places and relics. There will be no Mass, just as I could find no one to confess me or give me absolution.

“All that is, we suppose, as God wills it. But we have come this far, and we will kneel at St Thomas’ shrine. You will allow us so much, I think.”

At this, the man first looked incredulously at Agnes. Then, when she didn’t respond, he threw back his head and laughed at her — an unpleasantly loud sound that echoed around the nave and transepts before before losing itself, at long last, somewhere in the high vaulted spaces above them.

“I will, will I? And who are you, simple woman, to tell me so?”

At this, Hubert, who had been longing for this moment for some time now, made as if to spring at the man, brandishing like a weapon the great candle he was carrying in his arms. Agnes, though, with surprising speed, interposed herself between the two men and then, gently, put her hand on Hubert’s hand, stilling him.

Almost despite himself, as if held back by some unseen force, Hubert stepped back again, the great candle once again cradled, tenderly, to his chest.

Agnes spoke calmly and without irony.

“My name,” she replied, “is, since you so kindly ask, Agnes. I am the wife of John Wright, master carpenter, from Blakeney Haven in the county of Norfolk. This child is my son, Valentine. St Thomas of Canterbury, of his great mercy, cured my son of the fits that used to trouble him, God be praised.”

The man said nothing, so Agnes continued.

“Our parson, Sir John Clayton, gave us his blessing to travel here in order to give thanks to the blessed martyr St Thomas.

“Sir John, in case you do not know, is a weighty person. You may suppose, perhaps, that he is a simple village parson, some little low clerk of no learning. In truth, though, he was an executor of Sir James Hobart’s will, he is chaplain to my lord the Earl of Sussex — also, he was tutor to the son of my Lord Privy Seal — I mean, for clarity, Thomas Cromwell — and stands still in my lord Cromwell’s high regard.

“In brief, Sir John has the good favour of many proud and mighty men, as shall speedily become apparent to you if you hinder us.

“There is, however, a far greater reason still why you should allow us to do as we require. St Thomas himself told me in a dream that I was to come here. Three times, he told me.”

At this, the man laughed that same unpleasant, loud, mocking laugh.

Agnes, however, persisted.

“St Thomas, invincible knight of Christ, stood before me, as you stand there now, in this very place, dressed — just as he was at the moment of his martyrdom, under his rich robes — as a poor monk. He embraced me. He told me, a poor sinner, one who has sinned before God, that I was his sister and semblance. He told me that just as God gave him the thing that he wished for most, so should God give me the thing that I wanted, too — that being that my only child Valentine should be free from fits — only that I was to come here afterwards, make to all a true relation of my story and give thanks. Those were St Thomas’ words, praise be to God, when he spoke to me. Three times!”

By now a little crowd had gathered around Agnes and the angry man. The crowd was made up mostly of laymen in their smocks. Having spent decades as a master builder’s foreman, Hubert knew instinctively that these were builders’ labourers. He saw, too, a few monks standing by as well.

Briefly, a shadow of a doubt seemed to flicker across the man’s broad face. He stepped back, just slightly. He glanced at the men around him — the young labourers, half excited and half terrified at the task that lay ahead of them, the monks variously angry, half-stunned with grief or moving their lips in near-silent prayer — then regarded the little party before him.

“You will let us kneel at the shrine,” said Agnes, again. “You will let us do that much.”

The man cursed, looked down at the floor and up to the vaults, then turned his flushed face back to them once more, eyes bulging, furious — clearly unable to fathom why it was, exactly, that he was unable to resist Agnes’ confident persistence.

“Oh, very well then, simple woman!” he exclaimed. “What can it matter, now, if one more superstitious fool cries to that low traitor Becket, fraud of Cankerbury, fondly imagining that a few old dry pretended bones will do other than send you straight to hell for idolatry? Mark my words, though — you have only as long as it takes for my boys here to gather their tools together, so that our good and Godly labour can begin. After that, if you’re not out of this church, then it won’t be your sins you’ll be crying about.”

“God bless you, sir” replied Agnes. Taking Valentine by the hand and nodding to Hubert, she started off, very briskly indeed, along the short nave, towards the stairs that lead up in the direction of the choir.

* * *

Hubert, rushing along after Agnes but also looking back over his shoulder, saw that two monks were following them. He sighed and swore a great oath under his breath.

The two guardians of the shrine, though — for such he took them to be — were better than he expected.

“Stay a moment, my dear sister” said the taller of them, whose cowl covered much of his face. The wool of his habit, iron-dark, was coarse and very worn. “You have come far. Let us show you the way.”

“Thank you, sir, but St Thomas will tell me the way.”

“He will indeed. Let’s go up these stairs. We’re on the monks’ side, but I hardly think that matters this morning. There, by the way, is the spot where the martyrdom occurred — by that column, there. And there is where the blood and brains were scattered across the floor.

“Ah, poor Thomas, who for justice and the preservation of the rights of God’s church died under the four swords of four impious knights! Also, happy Thomas, blessed with martyrdom not only once, but now again!

“Those other stairs, by the way, lead down to the crypt, which is where the first burial took place, before the new work was done. If we had more time left to us today I would show you.”

Valentine, who was still quite young, was less interested in the tall monk’s words than he was in those marvellous blue windows. Looking up at them — lost in their stories — he stumbled slightly on the ancient, worn, uneven stairs. The other monk, shorter and less imposing than his brother, reached out in a matter-of-fact way and took the child’s hand to steady him. Surprisingly, Hubert found himself entirely untroubled by this.

There was no need to unlock the iron gates of the chapel, as these were standing open already.

A moment later, they all arrived at the top of the stairs, within sight of the shrine. Here they made proper reverence, first to God and then to the blessed martyr.

The taller monk, who had a commanding air, signalled wordlessly to Hubert that he might, at long last, set down his candle. Hubert did this with some gladness for, his physical strength and his devotion to Master and Mistress Wright notwithstanding, it was a very heavy candle.

The tall monk further signalled him to take his place a little distance from the shrine, near the the south west corner of the chapel, by the outer wall. There, he found that he was able to rest his aching back against the tomb of some great prince of the church, long dead, whose name now escapes me.

The air in the Trinity Chapel was very still. It smelled of old stone and frankincense, spikenard and dust, beeswax and eternity. The effect of this all was to make Hubert feel slightly dizzy — although, of course, thinking back on it afterwards, that might also have been that morning’s fast, the long journey behind him and the prospect of its end in sight.

Agnes, meanwhile, could hardly take her eyes off the shrine.

There had been no Mass of St Thomas at the shrine’s altar that morning. There were no candles lit, either on the altar, the beam above it nor indeed on the triforium. Some of the altar clothes had been roughly pulled aside, as if to expose the frank nakedness of the bare stone beneath — stripped, Hubert thought, like some condemned soul for execution. No singing rang out from the choir. The organ was silent. Still, despite all this, the wooden cover had been hauled up, so that St Thomas’ golden feretory, high up on its marble base, far above their heads, stood fully revealed.

Even in the weirdly crepuscular half-light of that dark September day, where the only illumination reaching the chapel had first to struggle through the strange poetry of those unearthly blue windows, the shrine seemed to glimmer, to glow— even to sparkle merrily amid the funereal near-darkness.

Agnes, looking up, took in the shimmering gold, the bulbous jewels, the bright intricate enamel-work — the vast, inexpressible, vibrant opulence of the thing. No one, surely, could have been wholly immune to the force of its sheer material worth. Agnes was, at the end of the day, a master artisan’s wife, from a long line of skilled artisans. She was not such a fool as to despise anything done skilfully, nor to discount the inspiration bound up in works so wonderfully made.

And yet, staring up at the shrine, she hardly noticed the gold, the jewels, or the richness. In truth, she was looking instead, with the eye of faith, into the glorious golden resting-place, seeking through and beyond it, for whatever was left of the saint and martyr. She was looking for St Thomas.

The taller monk, regarding her briefly, saw all of this, and was glad.

The shorter monk, for his part, while less commanding, was perhaps the more reflective of the two.

“My dear lady, I heard you say that your boy here was cured of the fits through the intercession of our own martyr, St Thomas of Canterbury. How, though, do you know that it was he who cured him, and not some natural or other thing? You are a doughty woman, not easily denied. Physic, efficacious draughts and medicaments, sweet airs, charms, the driving out of demons — you will have tried all of this. Why our St Thomas?”

Agnes did not take her eyes off the shrine.

“Sir, you speak the truth. I tried all those things and more. In faith, I would have tried anything, to undo the fault that I fear my sins engendered in Valentine, even at the moment of his creation.

“But, sir — and here, you are a learned man, and I only a simple woman, as that man in the nave rightly said of me — how do we know anything? I mean not simple things that one can see with the eye or hear with the ear — I mean things we know in our heart.

“How do I know that the sun is kinder than the sharp wind? How do I know that I love my son? How do I know that there is holiness in this place, beyond other places, here with St Thomas so near that one might almost reach out, if one could only stretch up a little further, and touch his sweet dear bones?

“That, sir, is all I can say on the matter — only that I am as sure of it as I am of God, or indeed of anything — although thinking on it, in my foolishness, I cannot tell you why.”

“The lady speaks well,” opined the taller monk, dryly.

“Indeed, the lady speaks very well,” replied the shorter monk, making a deferential little bow in his companion’s direction.

Suddenly there were noises — raucous, harsh, unpleasant noises — from down in the nave. Agnes looked away, then reached down and extracted a small, slightly grubby-looking canvas bag that had hitherto remained hidden, tied onto the strings of one of her petticoats. Carefully, she opened it, and poured the contents thereof onto her fine, long-fingered hand. Even in the bad light and at a distance, Hubert could see what she was holding — a handful of bright gold coins, and not a small handful, either.

“Here, sir, are my poor alms, such as they are. I wish to give them to St Thomas, along with the candle, and a few other little trifles.”

She held out her handful of gold.

The monks regarded one another for a moment. Then the shorter one spoke.

“My dear lady, your gift is very well intended. Please, though — if you would give alms out of your devotion, don’t give them here! Not today, at any rate. Go to the hospital in the town — any of the brothers will tell you where it is — and give your alms there instead. It is a worthy place, the hospital. More to the point, it is well loved of the burgesses. His Majesty will do it no harm — it will stand forever. But don’t leave these pious gifts, welcome though they are, at the shrine.

“Can you truly not see what’s happening, dear lady? If you leave your gifts here, the King’s commissioners will have all of it — the Exchequer will have it! Whatever is the point? You might as well throw your gold into the priory’s latrines, for all the good it will do to St Thomas and his shrine, today of all days.”

Agnes, however, was unmoved by this.

“But I’m not giving them to the Exchequer,” she objected, calmly, still holding out her hand. “I’m giving them to St Thomas, who saved my Valentine. And whatever happens after that — why, surely that is no affair of mine?”

With this, Agnes turned from the monks and set the gold coins down on the ground in a little heap, very gently, next to the shrine.

The shorter of the monks stepped forward as if to stop her but the taller one, silently, made a pre-emptory gesture, effectively ordering him to remain where he stood.

“The lady does well, too,” said the taller monk.

The other monk bowed, again, conceding the point.

Then, as they all watched her, transfixed, Agnes took from her finger her fine gold wedding ring, and the gold chain she always wore around her neck. From the fastening of her mantle she unpinned the brooch she had been given by the parson — this last an antique gem carved with the likeness of Venus, chased about with yet more gold, reputed to have come all the way from Rome itself, back in different times.

Stepping forward, she pushed all of these things, carefully and deliberately, through the quatrefoil openings in the side of the tomb.

There was no time now for Pater Noster, nor Ave Maria, either. Agnes spoke simply, more or less as she would have spoken to anyone else she loved.

“There, my sweet St Thomas, have those. Those are for you. Pray for us, pray for us! Thank you, too, for your charity to me and my Valentine. Also, St Thomas, if you will, please bless the rest of them — Master Wright, of course, and Sir John besides, for all his faults, although those are admittedly indifferent with my own — and bless all those others, too, for whom I am bound to pray. Amen.”

And with that, throwing herself quickly upon her knees — urgently, avidly —Agnes knelt before the base of the shrine. Leaning close to it, so that her hands rested against its smooth silky surface, she covered the strawberries-and-cream, blood-and-brains, pink-and-white stone with fervent, passionate kisses.

The men all marvelled.

Valentine had been standing next to Agnes. Half unwillingly, he left off admiring the zodiac signs laid into the Cosmati pavement. Shyly, he knelt beside his mother. “Thank you, St Thomas” he said, before giving the base of the shrine a single, tentative kiss.

The marble felt cold under his lips. What he felt, though, was not so much the cold of an inanimate thing, let alone a dead one, as a cold that burned like a kind of energy — vast and unknowable, almost frightening, only just under control.

Mother and son were there but for a moment, though, because it was just then that the broad-faced man and his gang of labourers came storming up into the Trinity Chapel, their tools clattering sharply against the stone, rending the sacred space with their shameless, triumphant ordinariness.

“That’s quite enough of that!” said the angry-looking man, red-faced and slightly breathless. Seizing Agnes and Valentine, he dragged them from the shrine and across the Cosmati pavement, all the way to the steps, where he more or less threw them down the giddy ranks of well-worn stone.

“To hell with you both, foolish bitch, foolish bastard boy, and all your superstitious, idol-adoring crew, too!” he shouted after them — and also after Hubert who, slightly stunned, staggered along in their wake.

The angry man’s shout, though, was more than a little muted. He had not forgotten what Agnes had said about Sir John Clayton. Also, there was something in Agnes’ manner that unnerved him. For years afterwards, her calm contempt would haunt him in his dreams.

The two monks, finally, were nowhere to be seen. Hubert assumed, probably correctly, they had slipped away amid all the confusion.

* * *

Agnes, Valentine and Hubert found their way out into the daylight.

What had started as a bright September dawn had matured into a cool grey mid-morning. A wind from the southeast send clouds scudding across a lowering, slate-coloured sky. Rain was on the way. The Kentish air was very soft. It reminded them all how far away they were from Norfolk, and how long it was since they had seen their homes, or known the comfort of familiar hearths. There was some sadness in this, as there always is at the start of autumn, but also a kind of resignation.

They stood in a little group, dazed, like sleepers suddenly roused from a dream.

The cathedral close, in contrast, was full of rude, raucous, prosaic life. They saw about them monks, townspeople, a little party of foreign visitors having something pointed out to them, as well as a larger group that was forming around some very richly-dressed personages off in the distance, having just arrived through the great gate.

Whoever these people were — the stocky, bandy-legged man with his cloth-of-gold doublet, fine fur mantle and gold neck-chain, the slimmer man in black damask, deferential and politic, cleaving close by his side — a crowd began to close round them, so that in a moment they were no longer visible, so entirely enfolded were they by the multitude of people. It was hard to see, from such a distance, but those joining in seemed to include some of Agnes’ companions from the journey down to Canterbury — the old lady, the lawyer, the friar, even the professional pilgrims.

Under other circumstances, I suppose, Agnes, her son and her husband’s foreman might have shown more interest in who these men were, and might indeed have joined ever-increasing crush surrounding them. As it was, though, it seemed quite enough to stand there by the cathedral, in the plain daylight, wondering that the world outside was still as it had been earlier in the day — recovering their breath.

After a little while, from inside the vast stony bulk of the building, from somewhere within its strange agglomeration of accretions and irregularities, chapels and antechapels, buttresses and vaults, the three of them heard first one loud crashing sound, and then another — as if something were being broken that could not easily be put back together again, even by a very good craftsman indeed. But it all felt rather distant, somehow, at least to Agnes and Valentine and Hubert, and no concern of theirs.

* * *

“Well, did you do what you came to do?” asked Hubert.

Hubert was feeling clear-headed again. He had found his boy and, after some searching, Jane as well, slightly red-eyed but otherwise none the worse for having failed, in the end, to reach the much-advertised shrine.

More to the point, at least in Hubert’s reckoning, he had at long last broken his fast with bread, cheese and good strong ale, offered to him by a passing monk who, he supposed, hadn’t realized that hospitality to strangers and pilgrims was no longer the order of the day.

Further, no longer weighed down by that candle, Hubert felt strangely carefree, unburdened — literally, as if a weight had been lifted from his shoulders. This was by no means an unpleasant feeling.

“Was that what you came to do? What happens now?”

“Yes, I have done what I came to do, God be praised,” replied Agnes, absently. She took a moment to stroke Valentine’s hair and straighten his shirt, looking at him lovingly and slightly critically, just as any ordinary mother might do. “Yes, now we can go home again.”

And that, rather to Hubert’s relief, is exactly what they did.

[Author’s note: John Clayton was rector of Blakeney (Norfolk) from at least 1519 until his death in 1541. A pluralist, he started his career as an associate of Sir James Hobart, attorney general to Henry VII. Later, he was chaplain to the first Earl of Sussex, and also for a while tutor to Gregory Cromwell, the son of Thomas Cromwell, sometime Lord Chancellor of England. In 1536 Clayton assisted the Earl of Sussex in restoring order after the Pilgrimage of Grace, where he was present at the dissolution of at least two religious houses. In his will of 1541, made less than three years after the events imagined in this story, Clayton left not only a series of highly traditional religious bequests, but also provision for the care and education of one “Valentine”, undescribed and otherwise unknown.]