Some thoughts on the chancel at St Nicholas, Blakeney

by Barendina Smedley

The enshrining of historical ‘facts’ is a curious business.

It is generally believed these days — by all sorts of people, which is to say, those who know very little about the Norfolk village of Blakeney and those who know quite a lot — that the chancel of the church of St Nicholas was built and used by the Carmelite friars who were at that time established in our village. This explains why the chancel and nave appear unrelated, why the standard of work in the chancel is so good, even why the priests’ door faces northward. But when pressed for additional details, silence descends. In truth, the case for Carmelite involvement with the chancel makes very little sense, isn’t supported by the evidence, and is almost certainly wrong.

My purpose here is to spell out why the Carmelite explanation doesn’t really work, and also to provide what seems to me a far more likely alternative backstory for the chancel at St Nicholas, Blakeney.

The origins of the Carmelite theory

Let’s look first, though, at how the Carmelite story got started.

The first evidence I have seen for this line of argument appears in the Blakeney church guide prepared in 1954 by the Rev. C. L. S. Linnell, incumbent of the nearby parish of Lethringsett. In this he acknowledges help from, inter alia, John Page ARIBA, architect of Blakeney’s newer rectory, built in 1924 and demolished in 2019, all which tells us something about Blakeney’s unsentimental attitude towards its own ecclesiastical heritage.

The Rev. Charles Laurence Scruton Linnell, for his part, was no casual clerical scribbler.

As well as writing several guides to north Norfolk parish churches, he was the author, along with the redoubtable Wilhemine Harrod, of the Shell Guide to Norfolk (1958). He also wrote Gresham’s School: History and Register, 1555-1954 (1955 — he seems to have served for a time as chaplain there, giving ‘lively’ divinity lessons), English Cathedrals in Colour (1960), Some East Anglian Clergy (1961), Norfolk Church Dedications (1962), The Diaries of Thomas Wilson (1964), and edited a number of Arthur Mee’s volumes in “The King’s England” series. In the 1930s Linnell had worked with the Norfolk Archaeological Society, including leading a dig in Salthouse churchyard. He seems to have held the living of Wiveton (1956-59) and was certainly rector of Letheringsett (1952-62). But despite the full bibliography and the short span of time separating his age from our own, he remains a remarkably elusive figure. I have not been able to find even a basic newspaper obituary for him, let alone a proper biographical notice. Linnell was, in any event, manifestly a capable historian, someone who knew his local churches very well indeed, and who, as a working clergyman, was generally alert to the practicalities of parish worship.

Yet he seems to have been responsible for introducing the theory that the Carmelites were responsible for the rebuilding of the chancel here. In his guide to Blakeney, he observes, correctly, that “the chancel has the appearance of being almost a separate church building in itself”.

He continues

This can be accounted for if the chancel was used as the conventual church for the Carmelite Friary, the conventual buildings of which stood on the site of “Friary Farm” near the old windmill due north of the church. Similar arrangements are known elsewhere, for example at Bungay a nunnery used the chancel as the nuns’ church. In support of this theory there is a thirteenth century doorway, contemporary with the rest of the main fabric of the chancel, facing in that direction.

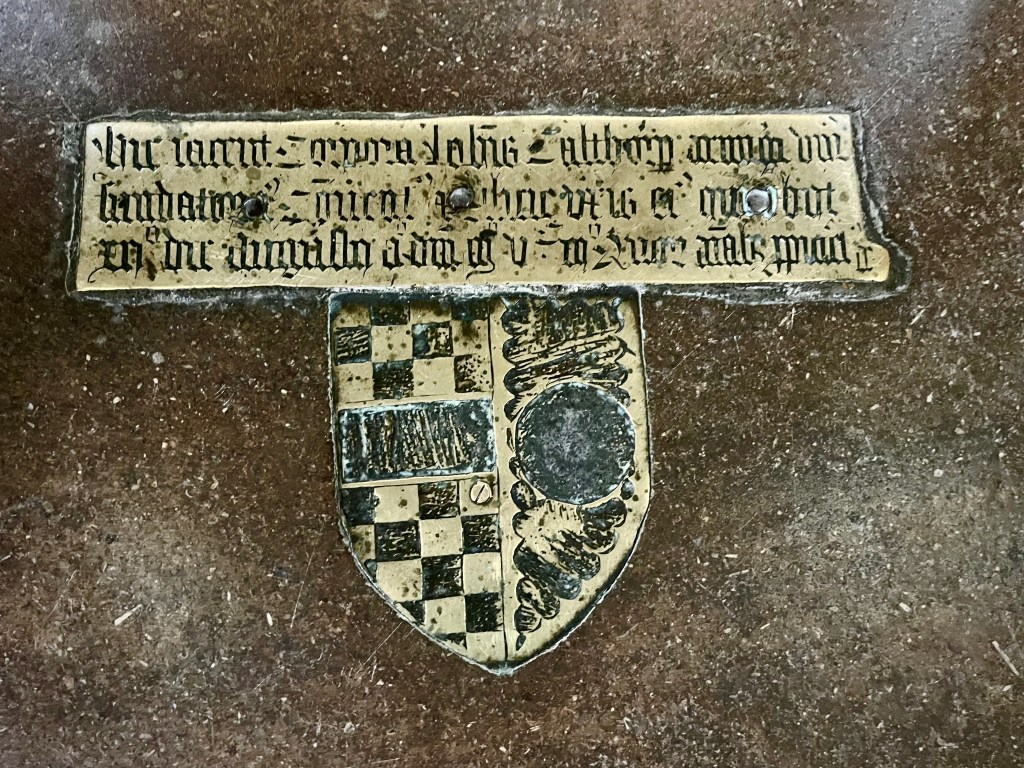

The thirteenth century tomb recess on the north side of the chancel, to the east of this doorway, is in a place where one would expect the founder’s tomb to be. Most convincing of all, though, is the will of John Calthorp (1503), in which he directed that his “Synfull body” was “to be beryed in the White ffryes of Sniterlie, that is to say in the myddys of the chancell”. John Calthorp was one of the benefactors of the Friary. His grave can be seen in front of the rood screen where there is a brass to his memory.

Linnell then gives the inscription on Calthorp’s memorial brass before adding

The Carmelite Friary was founded in 1926 [sic — an obvious typo for 1296] and the chancel at Blakeney, if not already erected, was certainly being built about this time. In other parts of the country the latter part of the thirteenth century might be a little late for such a splendid example of “Early English”, but in East Anglia it is as well to allow for a time-lag of fifty years or more in the development of the gothic style.

There’s a lot to unpack there.

Before going any further, though, it’s worth emphasising that Linnell nowhere says that the Carmelite Friary definitely built or used the chancel — indeed later on in the guidebook, when writing about the rebuilding of the nave circa 1435, he refers to the Carmelite connection as ‘possible’. In other words, as someone who was genuinely fascinated by and knowledgable about the history of the church and parish, he was pitching a case — not stating a fact. And yet later writers, perhaps swayed by Linnell’s obvious erudition, have somehow elevated the chancel’s Carmelite origins to the status of self-evident truth.

One admirable exception to this is local historian John Wright. In an extremely worthwhile article titled ‘The Origins of Blakeney Church’ published by the Blakeney Area Historical Society (available online here) Wright takes apart Linnell’s contentions, such as they are, effectively detaching the Carmelites from the story of the chancel and its origins. For anyone interested in the history of Blakeney, his article is essential reading. Happily, the current fold-out guide to St Nicholas, Blakeney takes Wright’s objections on board, dismissing the Carmelite connection as implausible. So perhaps the tide is turning, and it’s simply taking the popular understanding of this point a while to catch up.

And yet I think there is still a little more to be said on the subject — not only when it comes to countering Linnell’s arguments, either, but also in positing some sort of plausible alternative.

The puzzle of John Calthorpe’s (re)burial

Let us consider, first, the strange case of John Calthorpe (I am going to depart from Linnell in using the more conventional spelling of that particular surname) and how he ended up being buried in the nave of St Nicholas, Blakeney.

Although Linnell glosses his point about the burial of John Calthorpe as “most convincing of all”, it is not, in truth, a very good argument.

The main flaw in the argument is that, while Linnell’s theory is effectively that the Friary chapel and the parish church were identical — the same physical place — this is patently not correct. As Wright points out, sixteenth century testators sometimes made reference both to the parish church and to the Friary’s chapel in a way that shows that they were two different buildings — a point to which we shall return later. Further, a 1586 map of the port of Blakeney (see here), while more schematic than literally accurate in some respects, quite clearly shows both the parish church and the friary chapel as distinct, church-type buildings, and as the whole purpose of the map seems to be to record navigation-related features of the coastline, it would be odd if this feature weren’t correct. In short, at least by the sixteenth century, the friary chapel and the parish church were two entirely different buildings.

But the argument relating to Linnell is bad for another reason, which is that the alternative explanation for the disjunction between what John Calthorpe requests in his will, and what seems finally to have happened to his grave, is such an obvious one.

Wright dismisses Linnell’s claim by pointing out that Calthorpe’s family probably removed him from the Friary chapel and reburied him in the parish church. This is, I think, true. Yet it might be amplified. For one thing, the inscription on Calthorpe’s still-extant brass refers to him as uni fundatorum fratrum convent’ which would make sense if he were buried in the conventual chapel of a friary, but makes absolutely no sense if it had originally been intended for what was manifestly, whoever might sometimes have used it, the chancel of a parish church.

No, what must surely have happened is that John Calthorpe was buried in the chapel of the Carmelite friary, then at some point afterwards, reburied at St Nicholas, Blakeney.

We can conjure up the circumstances. John Calthorpe died in 1503, at the age of about 65 years. He was a local landowner, the senior member of a gentry family who had presided over the tiny hamlet of Cockthorpe for generations but who also held a manor in Blakeney. In marrying Alice Astley of Melton Constable, he had managed to reconnect the Calthorpes with a rather more prominent family who were also Blakeney landowners.

Indeed, I suspect this is why John Calthorpe was so particular about wanted to be buried in the chancel of the Carmelite friary. Various senior members of the Astley family were already laid to rest there — eg his father-in-law Thomas Astley (d. 1475) and his brother-in-law Thomas Astley (died 1500). The brass that marked his burial displays his own Calthorpe arms impaling the Astley arms, although the cinquefoil was apparently enamelled onto the brass (the weird-looking black hatched bits would all have been enamelled) and has now come away, making the Astley arms less obvious. The point, though, is this: John Calthorpe’s memorial would have advertised not only his own role as benefactor of the Carmelites, but also his dynastic union with the Astleys. At a time when the friary chapel was well-used not only by the friars themselves, but by the lay people of the village — and we know, from their testamentary bequests, that this was the case — this would have been a very good way for him to be remembered.

Or so it must have seemed in 1503. At the time of John Calthorpe’s death, his son and heir, Christopher Calthorpe, was about 41 years old. Christopher himself would die more than four decades later, in 1547, at the advanced age of about 85 years. Although he had normally styled himself ‘of Blakeney’, he chose to be buried in the parish church of Cockthorpe, where the Calthorpes had their longstanding family seat.

Thus we can see that in 1538, when it became clear that the Carmelite friary in Blakeney was to be dissolved — hence when the question presumably arose as to what should be done with his parents’ grave, which by then had then been in place for about 35 years — Christopher would have been 76 years old. Christopher, though, had a son and heir of his own. In 1538, James Calthorpe was about 31 year old. On his father’s death, he would become not only lord and master of tiny Cockthorpe, but would also inherit one of the three manors of which Blakeney had long consisted. The second of these manors would come to the Calthorpe family via their Astleys relations in 1589.

James Calthorpe had married Elizabeth, daughter of Robert Garnish (sometimes spelled ‘Garneys’) of Kenton in Suffolk. Elizabeth’s mother was the last of one of the various lines of Bacons, so rather as with his grandparents’ marriage, the effect was to reconnect the Calthorpes with another significant and influential north Norfolk family. The Bacons, too, had strong ancestral links with Blakeney — the parish church, as well as the Carmelite friary.

In 1552, towards the end of the reign of Edward VI, James Calthorpe would go out of his way to acquire the advowson of St Nicholas, Blakeney.

I think, although I cannot prove, that James Calthorpe was also responsible, soon before his death early in 1559 — at the young age of 50, possibly killed off by the outbreak of influenza that took such a heavy toll that year — for building the big tithe barn associated with Blakeney’s rectory. A five-bay, brick-buttressed, flint-built structure, the barn was rendered and also probably limewashed. Set upon a hill, it would have been visible for quite some distance around, projecting a very clear statement about where power and authority lay within what was, at the time, still a thriving, lively, lucrative commercial port. It would have been quite showy, but then that was probably the point.

These questions of status mattered. James Calthorpe and his elderly father would have been well aware that their distant cousins, Sir Philip (d. 1535) and Lady Jane Calthorpe of Burnham, were, through their Boleyn connections, even then caught up in the perilous game of snakes and ladders that constituted Tudor court patronage, and must have been watching their progress with interest.

We are also fortunate in being able to discover a little more about James Calthorpe from the contents of his will, which he prepared in August 1558, only a few months before the end of Queen Mary’s reign. The wording of this document is, perhaps unsurprisingly, cautious — James’s generation had learned how changeable the world could be — but still included a series of devout bequests. In a world where it was no longer possible to request intercessory prayers for his soul, James was clearly determined not to be forgotten amongst those who knew him best, or indeed amongst generations to come.

In his will, then, James Calthorpe ordered a new roof for Cockthorpe church, including the re-casting of the lead of the south aisle, which is where he wished to be buried. The chancel was to be tiled (i.e. given roof tiles), and a new window made there, depicting himself, his wife, their children and the arms of both families. He further requested that ‘a scripture of latten’ (a kind of brass) be placed over the grave of his mother Alianore, daughter of Richard Bernard and widow of William Brewes, who was already buried on the north side of the chancel. As we have seen, James’s father was Christopher also buried at Cockthorpe.

Unfortunately — and here he was even more unlucky than his own grandfather — James Calthorpe’s plan was not entirely successful. The brass he requested has gone, and the tomb that I think is probably his — a really handsome, rather unusual tomb chest — has lost its painted heraldry, so is now attributed by most sources to someone called ‘Sir James Calthorpe +1589’, who never existed. Sic transit gloria mundi.

This may sound like a digression, because it relates to Cockthorpe church, not Blakeney. If so, though, it is a digression with a purpose. I think James Calthorpe’s choices regarding his own burial and commemoration tell us something about his attitudes towards his family, his lineage, the status of his family and how they should be remembered. Was this a man who would have been content with the idea that his grandparents’ memorial brass was lying disregarded on the mud-caked floor of what was effectively a reclamation site, agricultural building or otherwise deconsecrated, decontextualised space?

In short, it seems obvious to me that, faced with the surely rather shocking dissolution of the Carmelite friary and its eventual sale to the Gresham family, James Calthorpe would have arranged for his grandparents’ remains, and also their brass, to be moved to where they have been ever since — which is to say, at the east end of the nave of Blakeney’s parish church. And here, it must be said, the Calthorpes had better luck, for although the heraldry on the brass may have lost its colourful enamel, and the brass itself may be worn down and increasingly hard to read, his grandfather’s monument could hardly be in a more prominent location — a fitting reflection of the Calthorpe family’s importance to Blakeney.

So if all that is true, then that 1503 memorial in the nave of St Nicholas, Blakeney proves nothing at all about the thirteenth century involvement of the Carmelites with the (re)building of the chancel there. Who, then, built that chancel?

An alternative explanation for that chancel

Spoiler: beautiful, elegant and functional though it is, we probably have to accept that we will never be certain who we have to thank for the existence of the chancel of St Nicholas, Blakeney. The evidence to prove this one way or the other may simply no longer exist. But if the Rev. C L S Linnell was allowed his speculation on this point, then perhaps I might be allowed to air my own best guess.

My prime suspect here is a man known variously as Peter de Melton (Meulton, Meuton) or de Constable, who died around 1236. He was the son another Peter, who served as sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk from 1201 to 1203. These men were both patrons of the living at Blakeney, and landholders here.

In 1222 this younger Peter petitioned — successfully — for Blakeney, where he was a major landowner, to be allowed to hold a weekly market and annual fair — this latter to be held on the feast of St Nicholas, ie the 6th of December — until such time as King Henry III came of age. As the market continued into the early eighteenth century, it is generally assumed that this permission was subsequently extended. In any event, the creation of this market and fair marked a major milestone in Blakeney’s development.

People who only know Blakeney in the present day may be surprised to learn that from the thirteenth century well into the seventeeth century, the ports at the mouth of the river Glaven — Blakeney, Wiveton and Cley-next-the-Sea — added up to a commercial centre of some importance. Salted cod and ling, sometimes caught as far away as Iceland, were particularly important, but the market in Blakeney would also have handled salt, wheat, barley, malt, flax, timber, bricks, tiles — as well as wine and other luxury goods. In the sixteenth century, coal began to be shipped in from Newcastle. So while some careless embanking and the silting up of the mouth of the Glaven put a stop to this in the early seventeenth century, for a good five hundred years or thereabouts, on a busy day the quay at Blakeney would have been crowded with visitors speaking not only Anglo-Norman but also Dutch, Low German, languages of the Baltic or of southern Europe — heaven knows what else — presumably discussing the price of salt cod, the latest news from somewhere else, tax, piracy, the likely turn of the weather.

In this context, Peter de Melton (for the sake of simplicity I am going to standardise his name thus here) is sometimes described, rather bizarrely, as a ‘fish merchant’. This really could hardly be more wide of the mark. He and his family were, in fact, hereditary constables of the bishop of Norwich. While they were really only fairly minor landowners — members of the local gentry, to use a mild anachronism, certainly not territorial magnates at the levels of, say, the Bigods or de Warennes, — they were figures who, at times, were capable of making an impact at county level. We shall consider them in more detail in due course.

First, though, let’s look at a few of the implications of this alternative origin story.

The chancel at Blakeney is Early English in style, with quadripartite stone vaulting and a particularly remarkable seven-light lancet window at the east end. I realise that holding the younger Peter de Melton responsible for the chancel at Blakeney effectively dates it not only much earlier than the 1296 proposed by Linnell, but also earlier than the ‘mid to late thirteenth century’ proposed by Wright.

But I’m actually quite relaxed about that. For all his erudition, Linnell’s assertion that “in East Anglia it is as well to allow for a time-lag of fifty years or more in the development of the gothic style” is simply nonsense. As we have seen, Blakeney was a community that made its living, in large part, from selling salt cod as far afield as Germany, the Baltic ports and the Low Countries, as well as London and other towns and cities along the east coast of England and Scotland. The creation of a market and fair in Blakeney only enhanced these links with a wider world. If Blakeney sometime seems remote in our present day — delightfully so, or otherwise — then we must guard against projecting this back on a very different time, when the North Sea in particular was more of a highway than a barrier.

Further, there is also no reason to assume that someone whose father had served as sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk, and who himself was constable to the bishop of Norwich, had unsophisticated or stubbornly provincial architectural tastes. It’s more likely than not that Peter de Melton had been to London and to Canterbury, perhaps even to continental Europe. He might have seen for himself the splendour and technical daring of Henry III’s new building programme at Westminster, perhaps even Saint-Denis or Notre Dame de Paris. His parish church at Blakeney was, necessarily, a rather more modest affair, but that is no reason why he, his friends and relatives, and indeed his builders shouldn’t have been influenced by contemporary building trends.

It also has to be said that 1230 is not, in itself, a ridiculous date either for the quadripartite vaulting at Blakeney, or for the lancet windows — even in Norfolk. St Mary, West Walton, for instance, is dated 1225-1240, with its detached tower in particular dated 1240. This seems to me to include elements not unlike those at Blakeney. At St Margaret, King’s Lynn, the arcade dates from about 1230. And Binham, as far as that goes, apparently displays the earliest example of bar tracery still extant in England — datable to before 1244, hence earlier even than that at Westminster Abbey. So again, Linnell was simply wrong in his patronising attitude towards Norfolk architecture.

What’s certain, though, is that the new chancel — which is even now quite tall and graceful by parish church standards — would have been shockingly different from the Romanesque or possibly even Anglo-Saxon structure that preceded it. It would also probably have been longer than the previous chancel. Indeed, it’s been suggested (see eg Warwick Rodwell, The Archaeology of Churches (2012), pp 72-73) that the need for a longer chancel, to take account of changes in ritual practice and the equipment and clergy necessary to carry these out, might often have been at least part of the motivation behind the decision to rebuild chancels in the late twelfth century. Other typical features reflecting changing liturgical practice might include a priests’ door, sedilia, Easter sepuchre and aumbry cupboards — all of which are present in the chancel at Blakeney. As for the stone screen separating the altar from the sacristy, I think it’s a reproduction of a fifteenth century introduction. The fifteenth century also saw the insertion of large new windows to the north and south of the chancel, with the exception of one small surviving lancet window to the south-east. Despite this, though — and despite later restoration campaigns — we can still get a pretty fair impression of what the builder of this chancel was trying to accomplish. And that fact that it’s still standing today surely argues that it was a good piece of work.

1222 and all that

The early decades of the thirteenth century may now seem, in all sorts of ways, dauntingly distant. Let’s consider them for a moment, if only to put into context the world in which this chancel may have been created.

In 1220, the body of St Thomas of Canterbury, who had been martyred fifty years before, was translated from the crypt of his cathedral to a specially-created golden shrine in the Trinity Chapel there, in what was possibly the most magnificent and high-profile religious events that has ever taken place in these islands. It’s not impossible that Peter de Melton, or members of his family, were present. At Blakeney, the altar in the north aisle of the parish church was dedicated to St Thomas of Canterbury (the one to the south honoured the Blessed Virgin Mary) and the period around 1220 was surely the most likely date for that dedication. The chapel of St Thomas there would necessarily have featured relics of the saint — and although we don’t know precisely what these were, because Blakeney was becoming a rich and well-connected place, we can guess that they were enviable ones. The existence locally of some form of access to this superstar saint would have been highly desirable, not only for Blakeney itself but throughout the Glaven area. The altar dedication would have made Blakeney into a suitable focus for micro-pilgrimages, with people from the nearby area seeking intercession in cases particularly relevant to St Thomas. He was and remains the patron saint of English merchants, including those operating overseas, and was also seen as the patron saint of London. In addition, though, he was also the protector of the secular clergy.

(We know, by the way, that there was an altar dedicated to St Thomas of Canterbury at this date, not least because the antiquary Charles Parkin (d. 1765) refers to it thus in his contributions to Blomefield’s Norfolk: “In this church were the gilds of St. Nicholas, St. Mary, and St. Thomas the martyr, and a manor is said to belong to the rectory.” His source was presumably gild certificates, although the altar is also mentioned in pre-reformation testamentary bequests.)

Meanwhile six years later, in 1226, the 19-year old Henry III made the first of many pilgrimages to Walsingham, effectively giving the Holy House and venerated image there a royal seal of approval that would remain in place right up to the Dissolution. While Henry III, a famously pious monarch, particularly admired his saintly ancestor Edward the Confessor, he was also devoted to the Virgin Mary and to St Thomas of Canterbury, with the latter of whom his family had enjoyed a complicated relationship. The north Norfolk village of Walsingham, for its part, soon became one of the most important pilgrimage sites in England, arguably second only to Canterbury, attracting all sorts of pious visitors. And while some pilgrims would have approached by road, others arrived by sea, including by way of the Glaven ports. This, too, would have put Blakeney in the spotlight.

Finally, it’s worth thinking for a moment about the political context. The reign of King John had ended with his death from a bad dose of dysentery in the autumn of 1216. He was not much lamented. Not only had he managed to lose most of his French territory, been excommunicated and forced to accept Magna Carta, but his power struggles with major landowners had resulted in a short but brutal civil war. The accession of his son Henry at the age of only nine years cannot have created a huge sense of stability. Very much against expectation, of course, Henry III proved to be one of England’s longest-reigning monarchs, lasting until 1272. In the short term, though, the real power lay in the hands of the barons, as well as a few men from modest backgrounds who, through their intelligence and hard work, managed to make themselves indispensable to the operation of royal authority.

The chancel at Blakeney was built in a time when going off to the Crusades was still a real option, when the rise of the mendicant orders was starting to transform the devotional landscape, perhaps even when the distinction between an Anglo-Norman ruling class and an Anglo-Saxon peasantry still felt very real. It’s a time that’s hard to recover now. And yet, even now, that chancel still exists, and may still have things to tell us about what went on, back in the early decades of the thirteenth century.

In search of evidence

Blakeney was certainly not Peter de Constable’s only base. I think his family seat was at what is now Melton Constable, just to the south-east of the hall there where a moated enclosure survived into the seventeenth century. (Although many sensible people hold that the name of the now-vanished village of Burgh Parva, just to the north of the railway-inspired present-day centre of Melton Constable, comes not from the Anglo-Saxon word for fortified settlement, but rather from the river Bure, I am not so sure.) Still, by the 1220s, he may have become convinced that Blakeney was a place in which he could suitably advertise his ambitions, for instance by rebuilding and rededicating his church there. Might he even have intended that chancel as his own place of burial?

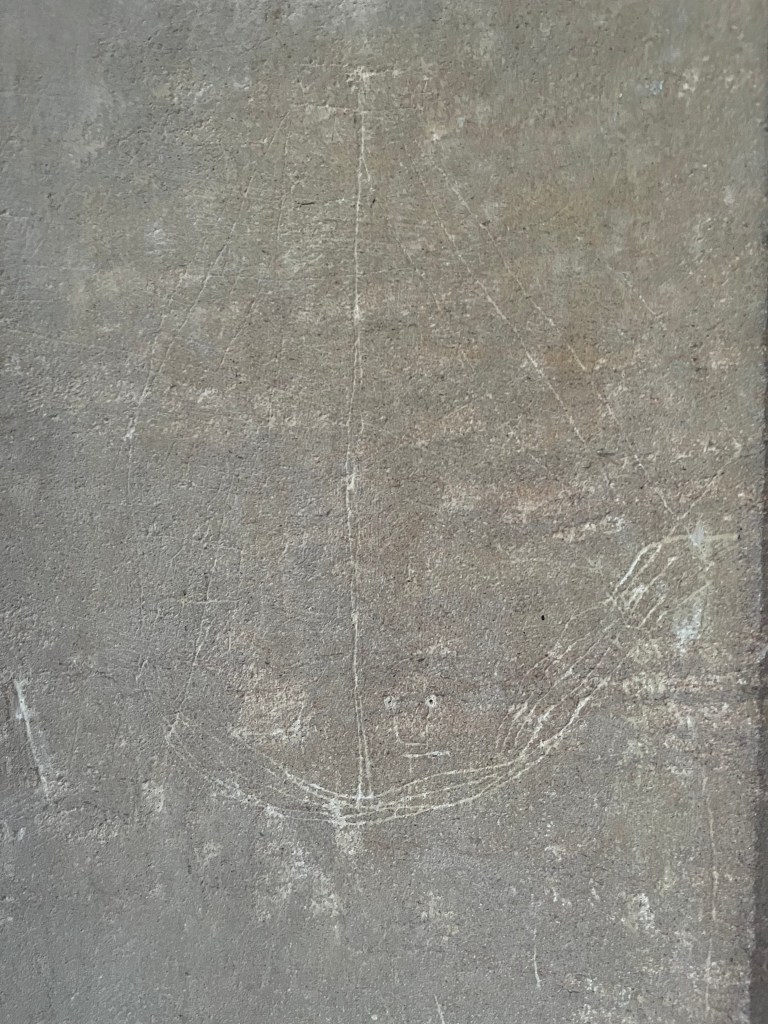

As with so many medieval churches in East Anglia, St Nicholas, Blakeney has an Easter sepulchre set into the north wall of the chancel. These structures — whether executed in freestanding timber form or built of stone, and indeed in the latter case, with or without an actual tomb — were often very elaborate and beautiful, and had been used since at least the 10th century as a part of the Passiontide liturgy.

The Easter sepulchre at Blakeney is apparently contemporary with the other Early English work in the chancel, except that the canopy over it was reconstructed during the general renovation of the chancel that took place in 1911, at the instigation of the Rev David Lee-Elliott. Had it ever been a tomb? It seems unlikely that it was obviously one in, say, the mid eighteenth century, as the Rev Charles Parkin would surely have mentioned this if so. But then a lot of destruction, ideologically motivated or otherwise, took place between the Reformation and the 1750s, and a great deal has simply been lost. And if this space has ever been investigated archaeologically — particularly prior to that 1911 renovation — then I’ve seen no sign of a report.

Meanwhile the most famous oddity of St Nicholas Blakeney is its distinctive second tower. Which is to say, in addition to the huge, indeed manifestly out-of-scale, 104 foot high west tower, the church also has a smaller, more gracile tower just to the north of the east end of the chancel. This smaller tower was rebuilt in the fifteenth century, at around the same time as the nave was rebuilt.

There has been a great deal of speculation over the years as to why this little tower exists. Was it meant as a beacon for ships, some have wondered, or as some other sort of navigational aid?

Yet the obvious answer is that, at least in the first instance, it was simply a stair turret connecting the chancel with the chamber that sits above the vaulted space below, lit by an east-facing window. The stair turret may have culminated in a little tower for a sanctus bell above that.

The tower is entered from what is now the sacristy — the stone screen separating the sacristy from the rest of the chancel dates from 1911, but apparently scars on the earlier floor showed the similar position of an earlier screen, and would explain the single lancet window lighting the space. Parenthetically, as well as two double aumbries set in the east wall, there is also an arched area immediately below the great seven-lancet window that might be simply a straining arch — but would also have fit another tomb. Was someone once buried there?

As for the rebuilding of the east tower in the fifteenth century, I am not so sure that the rather primitive windows lighting the tower date from this later period, as opposed to being reused from the earlier structure. In any event, access to this upper chamber appears to have been controlled very carefully — it was a very secure, if not particularly user-friendly space.

The upper room

The room over the chancel at St Nicholas, Blakeney really hasn’t received the attention it arguably deserves.

Having now seen it, I can exclusively reveal that — well, it’s quite a puzzle.

The approach from the stair turret takes one up a very narrow-treaded spiral staircase — it cannot have been meant for very regular, convenient or indeed dignified access.

Once in the chamber, the impression is one of considerable scale, but not much height. The walls are done in very neatly coursed flint, up to a certain level — and then after that, there are empty stone-faced mortices in a flint wall-surface that is suddenly full of quite a lot of good worked stone, which I’d guess had been reused from some other structure. Below, one can see the slightly unnerving ‘wrong’ side of the two quadripartite vaults below. Above is a newish roof (1911?) sitting on six massive oak joists.

The mortices are interesting. Was the pitch of the roof altered during the 1435 building campaign, to make it fit more agreeably with that of the new nave? This is my best guess. The mortices surely cannot have carried a floor, because this would have made both the door to the west and also the door approaching from the stair turret unusable. There is still some render covering the west-facing wall, implying that the space was intended to be used, and although it was hard to make this out in bad light, the render may show the pitch of an earlier roof. There is also a little bit of render low on the south wall, and patches near the stair turret.

At the moment, the structure of the two vaults is largely exposed. The exceptions are the west end of the room, where a timber stage is laid on top of them, and the east end near the door to the stair turret, where again, there is a little platform. There don’t seem to be any emphatic signs of the presence of an earlier floor spanning the space, except perhaps in the level from which the patches of render rise. If there was once a floor, it may have been a fairly sketchy timber one.

The space is currently mostly open, I assume to expose any structural issues that might arise, although in the way of all churches, there is also some miscellaneous lumber stored there. Most intriguing is a piece of stone that is either a pastiche Romanesque corbel depicting a lion’s head — or, just maybe, an actual Romanesque stone corbel. If it’s the latter, though, I’d love to know whether it came from the church. If it did, surely it tells us something about what was here before the thirteenth century chancel and the fifteenth century nave.

Clearly, then, it would be helpful if someone who actually knew about these things would not only look at this upper room, but also put something in print about it. Until that happens, though, I might as well hazard a few more guesses of my own.

While the room was apparently meant for some sort of use — otherwise it’s hard to explain the pretty prominent stair turret leading to it, the west-facing door out into the nave, even the render on the walls — it seems unlikely that it was ever a particularly large, accessible, well-finished space. I think the pitch of the roof was once quite a bit higher, but also springing from those mortices, so that the chamber was higher in the centre, but lower at the edges, than it is today — rather like a sort of long attic room. I see no sign that it ever housed an altar or that it was intended as a chantry chapel or other ceremonial space.

What, then, was this chamber intended for? No one seems certain.

In his thoughtful and detailed 1903 survey of the church in Norfolk Archaeology — one of the better accounts of our church — John Oldrid Scott commented on the chamber, although I’m by no means sure he actually visited it. He noted the existence of the east-facing window lighting the chamber, and also the blocked-up door opening into the nave.

Scott suggested that, in the days before the rood-loft was erected, at relevant moments in the liturgy the Gospel might have been read from this door. And here, of course, he may have been right. Certainly the rood-loft wouldn’t have been in place before the fourteenth century, and there may well have been a little gallery that could be entered from that door that would command a view out over the nave. This would agree with my intuition that while the upper chamber was meant to be accessible, it wasn’t intended for any sort of general, everyday use.

There’s another possibility, though, that seems even stronger to me, not least because it would make sense of the secure if not particularly user-friendly stairway, the west-facing door opening out into the nave at a very high level, but also the rather utilitarian character of the room. I wonder whether the room above the chancel might have been used for storing valuable relics. This would have kept them safe, but also allowed them to be displayed from the door on relevant occasions, such as feast days, and venerated by those in the nave below.

Later, of course — perhaps even by the fourteenth century — devotional fashions changed. At that point the relics, if they existed, might have been stored and exhibited in different ways, and the door eventually blocked by the newly fashionable rood screen, rendering the mysterious chamber behind it increasingly redundant.

How old is the parish church at Blakeney?

This discussion, such as it is, has concentrated on the chancel of St Nicholas, Blakeney. What of the nave? The answer is that while it’s entirely possible that a new nave was built at the same time as the new chancel — perhaps, as I’m arguing here, in the 1220s — it is also possible that an older nave was allowed to stand until it was rebuilt circa 1435. What is manifestly true, however, is that some version of the church very much pre-dates any thirteenth century rebuilding.

Our evidence here comes from the Domesday book of 1086. We know that, prior to the Conquest, ownership of Blakeney — or, rather, Snitterley, as it was known at the time — was fragmented into three holdings. One part belonged directly to the crown. The second part was held directly by Harold Godwinson, and under him, by Edric the Steersman, who may or may not be identical with the individual of that name who was steersman for King Edward the Confessor and who left for Denmark immediately after the Conquest. The third portion was also held by Harold, but under him was someone called Toki of Winterton, who, like Edric, also owned other land in Norfolk.

We know that the ownership of the church lay with the second of these portions — that of Harold Godwinson and his tenant Edric the Steersman — and that after the Conquest, this portion passed first to the Crown, who granted it to the bishop of Thetford personally, who in turn endowed his successors with it — successors who, when the see was once again moved to a new location, became the bishops of Norwich. And they, in turn, passed it on to a layman who will be discussed further in a moment. First, though, let us think about the church at Blakeney as it stood at the time of the Conquest, perhaps 160 or so years before the rebuilding of the chancel.

The Domesday book of 1086 not only mentions that Blakeney was furnished with a church, and indeed had possessed this church prior to 1066, but also sets out its value: the church was endowed with 30 acres of land, and worth 16d.

What does ‘worth’ mean in this context? Almost certainly, this was the value in tithes or other payments to the patron, hence the amount of tax it would bear — which was the reason why the enumerator bothered to list it in the first place, as the Domesday Book was a survey of property value, not some sort of census or exercise in topographical recording. While 16d. may not sound like very much, Blakeney was, in fact, by some distance, the most valuable church in Holt hundred. It may well, even then, have been a formidable church by local standards. Any church on the north Norfolk coast, particularly one so close to the mouth of a river, would probably have been hit quite hard by the successive waves of Norse invasions over the preceding centuries, sailing their longboats up the Glaven, perhaps sheltering in the haven before sailing off to wreak destruction somewhere else — and yet, even after all this, there was clearly a church at Blakeney that needed to be taken seriously.

As for who founded the church in the first instance, and when — we can only guess. It may have started life in the tenth or eleventh centuries as the private, timber-built chapel of a local landowner — although a flint-built structure is also possible — then gradually developed into a church for a community that increasingly found meaning and value in the sacraments of the Christian faith. The fact that the chapel of the neighbouring hamlet of Glandford seems always to have been attached to it perhaps hints at some sort of broader pastoral role. But again, we cannot know whether the clergy were monastic or secular, whether they were entitled to some sort of tithe-type support from their little flock, or where the balance of control stood between them and their patron. We can simply marvel at the fact that whatever was happening, it was happening here, in this very place, on this same hill with a view out over the marshes in one direction, back towards some low-rolling hills on the other. Isn’t it extraordinary to think that there might have been a moment when someone here saw a particular type of ship approaching and realised that the Vikings were coming, or when the news arrived that their own manorial lord, King Harold, had been defeated in battle and that their land was now subject to the Normans’ rule?

Let us return, at any rate, to a point of absolute certainty: the idea that, as the author of the relevant Wikipedia article fondly imagines, St Nicholas, Blakeney was ‘founded’ in the thirteenth century is absolute nonsense. By the time the present chancel was constructed, perhaps as much as 800 years ago, the church had already been in place for at least two centuries, probably longer.

Who was Peter de Melton?

I have already suggested that the person responsible for the rebuilding of the chancel at St Nicholas, Blakeney, was the younger Peter de Melton. One of the reasons I think this likely is that he was the patron of the living at the time. Indeed, one of the few things that we know about the early history of the parish church at Blakeney is that a family variously known as de Meulton, de Melton or le Constable had been patrons of the living of Blakeney, as well as major landowners in the parish, since a few decades after the Norman Conquest.

How did this happen? According to Blomefield and Parkin, one ‘Anschetel’, a forebear the de Melton family, was appointed constable (provost) to the bishop of Thetford (after 1094, the bishop of Norwich) soon after 1066.

To quote Blomefield:

The office of constable related as well to affairs of peace, as to military affairs. The Conqueror seems first to have appointed this office: his grand constable, or marshal, was styled Princeps Militiae Domus Regis, and was hereditary, of whose dignity and authority our statutes and histories afford many proofs, and many lordships were held under the King by virtue of it; and the same was in this family, the office appearing to be hereditary, and by virtue of it, held the lordships of Burgh, Langham, Bruningham, Briston, Sniterle, West Tofts, East Tudenham, Melton, etc.

‘Sniterle’ is, of course, Snitterley, i.e. Blakeney. ‘Bruningham’ is Briningham. ‘Langha’” here means Langham Parva / St Mary Langham. ‘Melton’ is now better known as Melton Constable, which of course differences the Melton in question from Melton Mowbray: one Melton belongs to the constable, the other to the Mowbray family. ’Burgh’ was the long-abandoned settlement of Burgh Parva located next to Melton. West Tofts was first converted into a Pugin-tastic extravaganza, then marooned inside the Norfolk Battle Training Area. East Tudenham is the odd one out here, lying quite far to the south of all these other places. I wish I knew what the ‘etc’ signified.

‘Anschetel’ may, by the way, be a Normanised spelling of a Danish name, which perhaps tells us something about the family’s origins. They may not themselves have been Norman occupiers, but rather may have been pre-existing local people co-opted by the Norman regime to enforce their policies at the regional level. See here for more details on the name itself.

Anglo-Danish or not, during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries then, the Constable / Melton family were figures of some importance within their own corner of north Norfolk. Yet it is very hard to learn much about them. Part of the problem is that the main line of the family died out before 1262, meaning that the surname didn’t receive the genealogical attention devoted to some other, more successful lineages. Still, there’s enough material out there to allow us to reconstruct at least part of their story — and plenty of scope to discover more in the future.

We can, I think, be certain that from soon after the Conquest until the mid thirteenth century, the de Meltons were people of some consequence — minor gentry occasionally rising to county-wide significance. Their holdings in the vills listed above would have given them a meaningful Norfolk base, with one concentration of holdings around what would become Melton Constable, and another in Langham and Blakeney. They presumably also benefited from their association with the bishop of Norwich, as well as the administrative and law-enforcement responsibilities connected with their hereditary role as the bishop’s constables. The bishop of Norwich had some sort of ‘palace’ in Langham, just to the west of the road that runs between Langham and Field Dalling. Its half-flooded moat still exists. Perhaps the de Melton’s property in Langham made it easy for them to attend the bishop, or his administrative staff, whenever he was resident there.

The de Melton’s rise to more than purely local importance seems to have culminated between 1201-1204 when Peter de Melton, son of Jeffrey de Melton, served as sheriff for Norfolk and Suffolk. This office was assigned by the monarch himself — in this case, King John, probably after lobbying by one of his advisors or other courtiers — and conferred considerable power on the recipient, who was expected to keep the king’s peace, to hold county court sessions, and to collect the annual shire payment to the king — with all the possibility for personal advancement this entailed. Whoever served as sheriff had to command respect in his own country, but might also expect to benefit, both in terms of patronage opportunities and financial advantage. And at a time of more or less nonstop threat of civil war, it was also a sensitive position.

This Peter must have died before 1214, because a document of that year describes his wife as a widow. His heir, Peter the younger, appears to have died by 1236/7, and left a son, Jeffrey, who was not yet an adult. Jeffrey, in turn, had died by 1256/57, without issue.

Jeffrey’s property descended to his three sisters. One of these, Isabel de Constable, married Adam de Cockfeld, and seems to be the one who ended up with the advowson of Blakeney. Another third of the estate, bequeathed to Jeffrey’s sister Edith, ended up with the Astleys, both in Blakeney and elsewhere. By 1287, Sir John de Cockfeld, nephew of Isabel, and son of Robert and Alice de Cockfield, had purchased Isabel’s portion. He was probably the justice of the king’s bench of that name, possibly based in Suffolk, and the son of someone whom we shall encounter later — someone who in 1232 was made sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk due to his strong ties with Hubert de Burgh, whom we shall meet in a moment. If so, in 1271 Sir John was receiving an annuity of £40 per year for his work as a justice. Like Peter de Melton, Sir John de Cockfield was a well-connected and ambitious Norfolk landowner. And if Peter de Melton turns out not to have been responsible for rebuilding the chancel in Blakeney, then Sir John de Cockfield might well be the next most likely suspect.

In any event, the advowson of St Nicholas, Blakeney would later be acquired by Bacon relatives of the de Cockfelds, before ending up, in 1362, in the hands of the abbot and convent of Langley Abbey, a Premonstratensian house.

We know one further thing, however, about the elder Peter de Melton — and it tells us rather a lot about the de Meltons and their social status.

Peter de Melton married Alice de Warenne, daughter of Reginald de Warenne, hence granddaughter of William de Warenne, second earl of Surrey (d. 1138). Alice was thus a direct descendent of Henry I of France (d. 1060) — not a particularly effective monarch, admittedly, but incontrovertibly a king. She was also the daughter of an Anglo-Norman magnate of real significance during the reign of King Henry II. Her father was present at the Council of Clarendon, served as sheriff of Sussex from 1168 to 1170, carried out diplomatic business for the crown, and persistently took the king’s side against Thomas of Canterbury. Her mother, in turn, was the heiress to lands centred on Bishop’s Lynn (now King’s Lynn) in Norfolk. Together, her parents were benefactors of religious houses including the Warenne family foundations of Lewes (Sussex) and Castle Acre Priory (Norfolk). In this context, it is interesting that the Taxatio of 1291-2 shows a portion (£0 4s 0d) of the value of the living (total of £33 10s. 8d) appropriated to the prior of Castle Acre. (See here.) The de Warenne family also made further gifts to Clerkenwell Priory, Carrow (where her sister was a nun) and Binham Priory. Her brother William founded a small house of Augustinian canons at Wormegay.

But it gets even better. William de Warenne’s daughter Beatrice (died c. 1214) was the first wife of Hubert de Burgh (d. 1243), variously a military commander, regent and royal advisor during the reigns of King John and Henry III, hence at various points one of the most powerful and influential men in England. English-born, unlike many at court in those days, Hubert seems to have been the son of minor Norfolk landowners — he grew up, I think, at the Burgh near Aylsham, not the one near Melton Constable — but raised himself to national prominence through his intelligence, persuasive speech and conciliatory manner. One of his brothers ended up as bishop of Ely; the other was deeply involved in the Norman conquest of Ireland. Hubert de Burgh’s influential position may have boosted the fortunes of his Norfolk neighbours, or at least given them extra prominence. When the nineteen-year old King Henry III first visited Walsingham, he stayed afterwards with Hubert at Burgh-next-Alysham — as he did at least once later on in his reign. Hubert held the office of chief justiciar between 1215 and 1232. There’s a famous comment about him from one of his contemporaries: “He lacked nothing of royal power save the dignity of a royal diadem”. He was the nearest possible thing in Plantagenet times to a prime minister.

The years immediately following 1222, the point at which Peter de Melton used what influence he had to gain a market charter for Blakeney, and possibly also the years in which he rebuilt the chancel at Blakeney, were precisely the ones in which Hubert was most powerful. (For anyone who wants to read about the political crisis of 1223-24, in which Hubert carried out a sort of coup d’etat at court, possibly advancing the de Melton family’s prospects in the process, this is a very interesting article: David Carpenter, “The Fall of Hubert De Burgh.” Journal of British Studies 19, no. 2 (1980): 1–17.) Then, for reasons not entirely relevant here, Hubert’s career went into a tail-spin and he died in disgrace — but by the time that happened, Peter de Melton had died too, leaving only a young and short-lived heir.

The point, though, is this: although we lack the details of their individual lives, the fact the de Melton family had a connection with the Warenne lineage and with Hubert de Burgh is yet another hint at their status and aspirations during the first few decades of the thirteenth century.

Why Blakeney?

We have seen that the younger Peter de Melton was closely connected with various Norfolk landowners, notably the de Warenne and de Wormegay families, with a strong record of practical support for religious institutions. It doesn’t take a huge leap of the imagination to think that he might have wished to follow their example, demonstrating his own piety and local standing by engaging in acts of devout patronage.

If the younger Peter de Melton were responsible for rebuilding the chancel at Blakeney, though, why did he chose to do this particular thing — to elaborate an existing parish church — rather than, for instance, further enriching an existing monastic house, or indeed founding a college of canons? There are two things to be said about this.

The first is that the early thirteenth century saw a shift in the norms associated with lay patronage of parish livings. While eleventh century patrons in England had apparently seen parish churches very much as their own private property — as implied by the way they are listed in the Domesday book — to which they could appoint their own clergy and manage in their own ways, the pendulum was shifting to a position where the church hierarchy exerted an increasing degree of control at the parish level. From the thirteenth century onward, this was reflected in many lay patrons’ decisions to make a gift of these patronage rights to a religious house, which is precisely what happened at Blakeney in 1362. But in the 1220s, Peter de Melton was still operating at a point where “his” parish church and its grandeur (or otherwise) reflected directly on him. Although the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 had, by clarifying the doctrine of transubstantiation, made the distinction between nave and presbytery more significant and also made the latter far less accessible to the laity, a lay patron like Peter de Melton retained some limited ability to control that sacred space. One way of expressing that control lay in rebuilding, rededicating and otherwise elaborating it, and these might have been options that appealed to Peter de Melton.

The other point, though, although it amounts to stating the obvious, is that of course we can’t ever really know, almost eight centuries after the fact, what the person who rebuilt that chancel intended, particularly by way of commemoration. As history dons of a previous age were fond of intoning, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. With its elegant double cube design — so suitable for choir stalls — that mysterious and much-ignored chamber tucked in above the vaulted ceiling, and the possibility that the Easter sepulchre once housed an actual tomb, it is not impossible that Peter de Melton, or whoever commissioned this building programme, made some sort of arrangement for commemorative prayers that has now been lost from the record.

Such an arrangement cannot have involved the Carmelite order, who only arrived in England in 1242, but it’s not impossible there was some sort of plan regarding, for instance, the Augustinian friars that might or might not have fallen through — perhaps because Peter de Melton died young and unexpectedly, leaving an heir who had not yet come of age. Could this have been the irritant grain of truth around which the myth of the Carmelites’ involvement actually formed?

The Carmelites in Blakeney

It is probably worth saying a little about the Carmelites and their association with Blakeney.

It has long been asserted that the Carmelite friary in Blakeney was founded in 1296 by Sir William de Roos and his wife Maud. (The fact that his copyhold tenants John and Michael Storm and John and Thomas Thobury donated 13½ acres of land for the building site would have been a decision on the part of Sir William, not that of the tenants themselves.) This pious gift, which also included the sum of 100 marks, came with the stipulation that the friars were to build a chapel and other related buildings on the land that had been given to them, where they were to pray for the souls of Sir William Roos and his wife Lady Maud. In addition to their hall and kitchen, the friars were to construct proper chambers in which to lodge Sir William, his family and his heirs whenever they wished to stay in Blakeney.

In making this gift, Sir William de Roos may have been inspired, at least in part, by the foundation of a Carmelite friary at Burnham Norton around 1242-47. The Carmelites had got their start in the Holy Land, and early enthusiasm in England for their rule and way of life can often be linked with those returning from the Crusades. Further Carmelite houses soon appeared around Norfolk, always located near busy ports: Norwich (1256), Lynn (circa 1260) and Great Yarmouth (1276).

And yet it took a while for the White Friars to become established in Blakeney — so much so, indeed, that some (including Wright, in the article mentioned above) have queried whether the 1296 document was entirely reliable, and suggesting that the work began after 1304 at the very earliest. In 1316 and 1331 the Carmelites’ site was further extended, each time by a few acres. Not until 1321 were the chapel and all the other buildings completed — a gap of 25 years from that putative foundation date.

Alas, this would have been too late for Sir William, who died in 1316 at the age of about 61 years.

Sir William de Roos (or, to give him his later title, the first Baron Roos of Helmsley) was yet another territorial magnate with regal connections. His great grandmother had been the illegitimate daughter of William the Lion of Scotland (reigned 1165-1214) and because of this, Sir William was a claimant, albeit an unsuccessful one, to the throne of Scotland. His wife Maud was, for her part, the daughter and co-heiress of John de Vaux (d. 1287), who in turn was a military commander and courtier of Henry III, sometimes sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk, and governor of Norwich Castle. Lady Maud’s ancestor Robert de Vaux had founded Pentney Priory, a house of Augustinian canons, near King’s Lynn circa 1130, endowing it with, among other things, the advowsons of six churches. I think it was this Robert’s son, also named Robert, who was later excommunicated by Thomas, archbishop of Canterbury, for a dubious transaction involving Pentney Priory. Religious houses and their vicissitudes were familiar matters to the de Vaux family.

In any event, returning to the actual subject here, it was through the efforts of Sir William’s son and heir William, second Baron Roos, that the Carmelite priory at Blakeney was finally completed in 1321. Like his father, however, William had interests in plenty of other parts of England. He was buried, as were his father and his grandfather, at Kirkham Priory, yet another Augustinian priory, this time near Helmsley in Yorkshire.

Sir William and Lady Maud had manorial holdings in Blakeney, although to say — as some sources do — that Sir William was “lord of the manor” is perhaps putting it a bit strongly. The de Vaux family had been granted lands in Blakeney, Cley and Holt immediately after the Conquest; after the death of Lady Maud’s father, some of these came to Lady Maud and some to her sister. Meanwhile, however, as we have seen, other manors in Blakeney belonged to other landowners — as did property in the closely inter-related Glaven ports of Wiveton and Cley — so the idea that the de Vaux / de Roos families were somehow pre-eminent there probably isn’t right. There were certainly other wealthy, well-connected and powerful people on the scene. As is often the way with ports, Blakeney was, and probably has always been, more an scrappy oligarchy than an autocracy.

Still, that provision regarding ‘proper chambers’ for the family to stay in whenever they visited Blakeney is quite striking — and not only for its amusing hint that Blakeney has always had a second homes / holiday lets issue, even in the late 13th century, either. It surely suggests that by the 1290s, figures of national importance, like the barons de Roos and de Vaux, thought the port of Blakeney was worth visiting, presumably for its trading links, although perhaps also for its proximity to Walsingham and Bromholm. And that, in turn, suggests that by the 1290s, Blakeney was already a place of significance — not that the foundation of the priory made it significant per se.

In the late 13th century, the mendicant orders in general and Carmelite friars in particular were an up-to-the-minute trend when it came to lay patronage, with their high levels of education, their popular preaching, their interactions with the local community, and their austere way of life all much admired.

This, I think, is why the de Roos / de Vaux families had turned their attention to founding a Carmelite priory in Blakeney — doing so associated them with an advanced form of spiritual practice in an up-and-coming, thriving part of Norfolk. And indeed, the Carmelites at Blakeney would thrive, continuing to receive gifts and bequests from all sorts of local lay people until, in 1538, the dissolution of the monasteries brought a halt to all of this, and to so much else besides.

Rejecting the Carmelite connection

Having looked at the circumstances of the Carmelites’ arrival in Blakeney, let us return, briefly, to the substance of Linnell’s argument. Is it likely that the Carmelite friars rebuilt the chancel at St Nicholas Blakeney as their own conventual chapel?

No, not really. We know both that in 1296 the friars were enjoined to build their own chapel as a part of the new foundation at Blakeney, and that by 1321 they had finally done so. It is hard to see why they would have concentrated their efforts on rebuilding a rather elaborate if, by that point, architecturally retardaire stone-vaulted chancel instead of creating, as they clearly did within a decade or two, a chapel of their own, conveniently located within their own conventual buildings. And it’s entirely clear, by the way, that their church really was down near the sea, where their other buildings stood. Not least, as late as 1586, an illustrated map of Blakeney haven depicts the friary very distinctly — and while that map is fanciful in many regards, it’s probably accurate as far as landmarks along the shore are concerned.

Is it impossible, though, that, for some reason — perhaps because it was taking them a very long time to build their own chapel — the Carmelites might briefly have been allowed to use the chancel of St Nicholas Blakeney for their own prayers and preaching? This is, at least, conceivable — but it still isn’t very likely.

First, although there are cases where a parish church was shared with a religious order, the order involved was usually the Black Canons, i.e. Augustinians, who included secular (i.e. non-monastic) priests. At Weybourne, for instance, I think it is right to say that the parish church was shared with a tiny priory of Black Canons (ie Augustinian friars), as was also the case at Sheringham and Binham. But what was intended by the Carmelites at Blakeney, and what seems to have been achieved there, wasn’t a pocket-sized college of canons — it was a proper Carmelite priory, adhering to the rule of their order. Also, we tend to know about the situation in these shared churches because there is plenty of documentary evidence confirming it. This is not the case at Blakeney.

Secondly, it’s worth noting that not all secular clergy, let alone monastics, were particularly thrilled by the arrival of a group of mendicants in their midst — mendicants who, through their preaching and their practice, might well divert both the devotion and pious gifts of the local laity. So why encourage them by harbouring them in a parish church?

Thirdly, there are serious practical issues. We know that regular clergy were presented to the living at Blakeney from the late 13th century onward — and it’s not unreasonable to assume that this was the case earlier, too. So how would they have coexisted with a group of Carmelite friars, observing their liturgy, preaching sermons, keeping to their rule? It makes no sense.

Also, while the Carmelite friary at Blakeney was largely destroyed in the centuries that followed the Reformation, enough survives that there is no mystery whatsoever as to where it was located. For instance, a very long section of medieval wall — complete with beautiful, careful flintwork — still separates the the demesne of the former friary from what was once a busy port and coastline. Behind that, the buildings of Friary Farm — a delightful 17th century building with additions from later periods — include not only medieval brick and blocks of dressed stone (an eye-catching rarity in this part of the world) but also sections of wall that surely date from pre-reformation period. From this, we can make an educated guess as to where the main buildings of the Friary were sited. And if this is correct, even today, a walk from the chancel of St Nicholas Blakeney to what might reasonably be supposed to have been the refectory takes at least five minutes, perhaps as much as seven minutes.

Meanwhile that walk would, I think, have taken the friars, on their way to say their nine canonical hours of the day, including their 2 am Vigil), across what was, at the time, the village marketplace. Is it really sensible to think that the Carmelite friars would have done this, day in and day out, in all weathers, for years on end? Or is it not more likely that, like other normal Carmelites throughout the world, they simply built their own conventual church, located next to their dormitory, refectory and other essential buildings, within their own large, walled, designated site?

Finally, if the Carmelites really had any kind of formal rights with respect to the chancel of a parish church — which was, let’s recall, a rectory, with the patronage from 1362 onward in the hands abbot and convent of Langley, a house of Praemonstratensian canons — it’s odd that no evidence of any of this Carmelite takeover appears in the records of any visitation, let alone in the Valor Ecclesiasticus of 1535, or indeed in any legal documents, including testamentary bequests. The case mentioned by Linnell — that of Bungay, where a Benedictine nunnery became a parish church after the Reformation — isn’t really a parallel, as it was clear that the church was Benedictine before the Reformation, secular afterwards — never some sort of hybrid.

Points of intersection

There are, however, two points of connection between the Carmelite friary and St Nicholas, Blakeney that deserve notice.

The first relates to a few of the choir stalls now located in the chancel. Here, we need to return to Scott’s 1903 description of St Nicholas Blakeney, mentioned above:

The stalls are of two designs, and some of them (four on the north side) stood, before the [1880s] restoration of the church, in the nave, forming a part of what was known as the Priory pew. They were supposed to have been brought to the church from Blakeney Priory. There are some coats of arms cut in the misereres that might possibly throw light on this.

Indeed they might.

These four are now, I think, still on the north side of the chancel, nearest the altar. They stand out, if only because the other stalls, although attractive and suitable, either date entirely from the 1911 renovation programme, or are so heavily ‘restored’ that what information they offer is limited.

Of these older misericords, two include arms — four shields in all. These were interpreted by the Rev Edmund Farrer, in his Church Heraldry of Norfolk (1889) — presumably seen by him when the misericords were still part of the ‘Priory pew’ mentioned above — as follows:

On a chevron, three escallops: ?

On a chevron, three cinquefoils or roses: Knowles?

On a chevron, three cross-crosslets fitcheé: Wylton / Wilton?

A cross moline: Owydale / Uvedale / Udale or possibly Beke

Farrer also lists another set of arms, not currently grouped with the choir stalls above:

Two chevrons: Dalling?

Three cinquefoils: Bardolf

Unfortunately, none of these names has any obvious connection either to the known history of St Nicholas Blakeney, or to Blakeney’s Carmelite friary, except that in 1329/30 Thomas de Estley (i.e. Astley) and Sir Edmund Bacon were tenants of Lord Bardolf, who in turn held his Blakeney property from the Bishop of Norwich.

So perhaps they didn’t come from the friary after all, or perhaps they reflect the names of benefactors who have faded from the record. Also — as quite a few people have pointed out by now, the designs on these misericords, on which the strictly celibate, all-male Carmelite friars presumably leaned at all hours of the day and night, look remarkably like a schematic renderings of a human uterus and ovaries. All of which demonstrates that there is quite a bit that we do not understand about the medieval world, and still much fruitful work to be done.

For one thing, I’d like to know whether the 1880s campaign of restoration involved stripping out old box pews — which sounds as if it might have been the case. Some of the other extant choir stalls appear to incorporate earlier material. Was that, too, salvaged from box-pews in the nave? And if so, where had it come from in the first place?

As far as that goes, at what point were the choir stalls inserted into the chancel? Were there ever choir stalls there at all, prior to the Victorian era, or even the early twentieth century? In a non-collegiate church, it’s not entirely clear to me what the point of them would have been — those are an awful lot of seats if the intention was simply to seat secular clergy — and yet there is no sign that Blakeney was ever a collegiate foundation.

Certainly, though, most of what we see in the choir stalls dates from the Rev Lee-Elliot’s tenure. C.f. this notice in the Downham Market Gazette, from 13 May 1911:

BLAKENEY. CHURCH RESTORATION – The work of restoration of St Nicholas Church goes on apace. The Rector has decided upon a thorough repair of the chancel. The beautiful wood work is to be reverently repaired, and towards the expenses a lady, who for the present desires to remain anonymous has promised to give the oak screen, the choir stalls, and the wood work, to the value of £1,000.

I think the lady may have been Lee-Elliot’s wife. In August, the Downham Market Gazette, which seemed strangely fixated on this subject, reported more fully:

BLAKENEY. CHURCH RESTORATION. At Norwich Consistory Court on Saturday, before Mr. Chancellor North, Mr. F. R. Eaton, on behalf of the rector and churchwardens of St. Nicholas’ Church, Blakeney, applied for a faculty to make extensive repairs to the church at an estimated cost of £2000. It is proposed to take off and recast the lead on the roof, to make good all timbers, etc, to repair the stone work, to open and restore three windows and one doorway in the north wall and one window in the south wall at present blocked up, to relay the floor with a bed of concrete, to pave with stone and wood certain parts, to refix memorial slabs, to re-arrange, restore, and extend the choir stalls, to provide a new choir oak screen, to erect a carved oak Calvary over the present rood beam, to erect a carved oak case to the organ, to insert a painted glass in the window of the Lady Chapel, and to erect therein a new reredos, altar rail, and furniture, and to pave the floor with marble. Mr. Eaton added that a painted glass had been inserted in the west window without a faculty, and he asked that a faculty confirming this might be granted. Citation issued.

All of which is a reminder of something that can hardly be repeated often enough. For all its deep history, the great majority of what we actually see when we look at the fabric of St Nicholas, Blakeney today — right now, in 2023 — is the work of the 1880s or later. The diocese of Norwich and the PCC were very casual about the decision to flog off Blakeney’s 1924 ‘New Rectory’ — a decision that led almost ineluctably to its demolition — yet in truth, much of their Grade I listed parish church is scarcely any older than that now-vanished building.

There is one further piece of evidence linking the Carmelites with St Nicholas Blakeney, mentioned by Wright in his article. It concerns John Barker, a wealthy and pious inhabitant of Blakeney who made his will in February 1536, i.e. 1537 by our reckoning.

By that date, the writing was on the wall for all sorts of aspects of traditional religion. Barker knew this. When writing about his bequests to the gilds of Our Lady and St Nicholas in his own parish church — giving each of them 6s 8d — he added the stipulation “so they contynewe”, before setting out what should happen if they didn’t, in fact, continue. He also left 5 marks for the repair of the church and asked, rather touchingly, to be buried “in the mydde alie nighest the Stolye ende where that I am most accustomed to sett” — i.e. he wanted to be buried next to his usual seat.

Barker left quite a few other devout bequests, including asking that a secular priest sing for his soul, his friends’ and benefactors’ souls for an entire year in the church of St Nicholas, Blakeney. Yet he also left 20s to the “ffryers of Snytterlye” (ie Blakeney) to sing two trentalls, “the oone within Snytterlye churche, the other at ther place immediatelie after my departyinge owte of this worlde”.

Barker is the only testator I know of who requested this dual commemoration. It’s hard to avoid the suspicion that he had a personal attachment to the idea of being commemorated in death at exactly the same spots where, in life, he had enjoyed the familiar routines of parochial religion — amongst the same people, still part of his own community and their collective memory. He must have admired the Carmelite friars, but at the same time, his language makes it very clear that while he wanted them to sing for his soul in his own parish church, they also had a conventual church of their own. Further, it shows that having the friars sing for his soul in the parish church was something that needed to be done by special request, i.e. it required clear stipulation. The friars’ church and the parish church were not, at least by 1537, the same thing.

Barker’s will was proved on 26 September 1537. Its provisions offer evidence for how, quite literally on the eve of religious reformation, the local laity were able to use their own agency — their spending decisions, their imagination and initiative — to blend support for mendicant orders with corporate parish worship. In doing so, Barker and his neighbours may have been motivated not only by trends in devotional ‘fashion’ — for the mainstream East Anglian faith of the early sixteenth century was very much centred on the parish and on commemoration, just as that of the early thirteenth century had focused much more on the doctrine of transubstantiation, veneration of saints’ relics and support for monastic orders — but also on personal choice.

These early sixteenth century wills open a window on what relatively ordinary people thought about their parish, their faith, how they wanted to be remembered. We know so much more about them than we ever will about their thirteenth century predecessors. Over the decades that followed, however, opportunities for self-expression of this sort were to narrow considerably — as, for that matter, did the relevance of the chancel. Visitation returns for the parishes of the Glaven valley make clear that by 1600, incumbents such as the scandalous, possibly puritan Rev James Poynter saw very little need to maintain the chancel, let alone elaborate it. Indeed, although the decades around the Civil War probably saw some developments there, it’s quite striking that the next major intervention in the chancel at Blakeney of which we have any record occurred either in the 1880s, as mentioned, or perhaps even as late as 1911, when the Rev David Lee-Elliott evidently wanted to convert his existing presbytery into a more suitable setting for Anglo-Catholic liturgical practice.

Finally, let us deal with Linnell’s very worst argument for a connection between the Carmelite friary at Blakeney and the parish church there. This is his claim that because the Carmelite friary lay directly north of the parish church, and because the priests’ door in the chancel faces north, this proves that the Carmelites regularly used this particular door.

In fact, at whatever point in the thirteenth century the chancel of the church was constructed, there would have been only one building in Blakeney of any significance that stood to the south of the church — and that was the rectory, assuming that it stood then, at least in some sort of form, roughly where it does now — which, for what it’s worth, is where I am writing this.

(For clarity, the building in question is now the Old Rectory. Its successor, as we have seen, was the ‘New Rectory’, built in 1924 and demolished in 2019. The current rectory is a recently-constructed house on the other side of the New Road, formerly known as Puddleducks.)

We know from terriers stretching back to the mid eighteenth century that what is now the Old Rectory — a building that dates back to 1518, perhaps earlier — stood within its own glebe, which may well be the same land with which the church was endowed in the Domesday Book of 1086. So while we cannot prove conclusively that the parsonage has always been in the same spot, it seems more likely than not. But if this is right, the parsonage will always have been to the southwest of the church — facing away from the priests’ door in the chancel — on the other side of the ancient road that connected the high street with the first bridge across the Glaven, then Holt, Norwich, London.

To be fair, Linnell’s argument wasn’t entirely ridiculous, because it’s often said that the location of the parsonage is the prime determinant of the position of the priest’s door. But like many things that are often said, this one doesn’t bear much scrutiny. By way of example, several parishes in this area have north-facing priests’ doors, with their parsonage located to the south. Examples include not only Blakeney, but also Wiveton and Morston; at Langham, the parsonage is directly to the east.

In all these cases, the reason for the north-facing door is surely a practical one: that the bulk of the settlement in question was located to the (ecclesiastical) north of the church, not the south.

In Blakeney, the topography explains a lot about the position of the priests’ door. The parish church at Blakeney seems from the earliest times to have been set on the highest spot in the parish, a sharp little hill rising up to more than 100 feet above sea level. The quay lies to the north, with the historic spine of the village formed by the street that connects the two. Traditionally, the market stood immediately north of the church, as mentioned on the Calthorpe map of 1769 — probably occupying the space now filled by the New Road and the large area of lawn just south of the Friary Farm caravan site.