The Excavation

by Barendina Smedley

“’Tis the solitude of the Country that creates these Whimsies; there was never such a thing as a Ghost heard of at London, except in the Play-house.” Joseph Addison, The Drummer (1716)

“I hope you will consider it no impertinence, my dear sir, that I should ask such a thing, but in truth I can no longer restrain myself. Sir, have you never felt an inclination to investigate what lies beneath that raised bank of yours, over there on the lawn?”

The Rev Mr Calthorpe paused, regarded his cousin briefly, then with infinite care and exactitude placed a slip of paper to mark the passage that he’d been reading, closed the book so gently that the gesture elicited no sound, and laid the little volume on the table next to him, where it joined the familiar company of candle, pipe, jug of claret and half-empty glass.

Mr Calthorpe did these things slowly and deliberately, not because he was old or infirm — for he was, in fact, a good decade or two younger than you would probably think him to be, were you to meet him in the high street, and in excellent health, too, thanks be to God — but because doing so gave him time to reflect, not for the first time, on why it was that the young were so full of zeal to do things.

Why not leave the raised bank behind the parsonage just as it was, and had presumably always been? Why innovate?

But because Mr Calthorpe was a very kind man, and sometimes even a politic one, he sighed, gently, and said none of this to his cousin.

The young Rev Mr Chambers, meanwhile, wondered whether he had gone too far. For all his apparent self-assurance — coaxed into being at Wykham’s two great foundations, successively if not definitively — he nevertheless remained sensible, when visiting Mr Calthorpe at his Norfolk parsonage house, that he was very much the poor relation.

For while Mr Calthorpe might appear, dozing quietly before the fire in his ancient Norfolk rectory, the simple sort of country parson whose quotidian predicaments and catastrophes might bulk out a Covent Garden farce, he was indeed, as all the world knew, younger brother and heir to Lord Calthorpe of Calthorpe Hall, Calthorpe, in the county of Suffolk — this latter personage recently promoted from Gentleman Usher Quarterly Waiter in Ordinary, to the infinitely preferable role of Yeoman of the Removing Wardrobe, no less, to His Majesty King George II.

Indeed, to a degree, the burdens consequent on this high office occasioned the scene before us. For while in most years the Rev Mr Calthorpe, his young cousin and indeed many other sprigs of the venerable Calthorpe family tree would keep keep their Christmases at Calthorpe Hall, in this year 1741, Lord Calthorpe was quite positively wanted at Court — less, it must be said, for the purposes of the Removing Wardrobe (whatever these might be) than for some internecine bloodletting within the circles of the higher Whiggery (similarly obscure, if perhaps more consequential).

Or to put it more simply — for you are already restless, and wish me to get on with this winter’s tale — on the one hand, Mr Chambers was interrupting Mr Calthorpe’s peace because he lacked any other place in which to spend the season of goodwill, and on the other hand, Mr Calthorpe accepted this imposition out of his own native benevolence, coupled with a sense, vague yet nagging, of the need to find his cousin a living suitable not only to his obvious wit but also his august connections, however attenuated these latter might be.

Such, then, was the situation.

Mr Calthorpe regarded his cousin with equanimity.

“No impertinence at all, sir — your query is, as ever, a reasonable one! — but I must say that I have felt no such inclination. Oh, I know ‘tis the fashion these days to poke at every old dung-heap and midden in the hope of discovering Julius Caesar’s chamber pot or Boadicea’s long-discarded thimble, and to convey these precious relics down to Piccadilly where learned men can argue over them and write them up in learned treatises, but I rather doubt my sorry old raised bank will reward anyone’s poking. ‘Tis is my conviction, sir, that rather than being thrown up by Claudius or Prasutagus, or some other ancient, that bank was constructed by a predecessor of mine here, less as a tomb or reliquary than for the worthy purpose of catching a glimpse of the sea, or perhaps keeping old Ezekiel Rudd’s grandsire’s cattle away from the parlour windows.”

“Your predecessor, sir? Do you mean the non-juror?”

“No, sir, I mean the proto-Arminian, if such he was —”

“Sir Nathaniel Bacon’s enemy, sir? I thought him a hot gospeller and roaring protestant, sir?”

“He was surely no such thing, sir — more likely he were a wizard and necromancer! — but leave off this, for this dead man’s failings are by-the-bye, and long since buried there. What I mean, sir, is that the bank is a mere century and half old, or so I have been led to suppose, hence not worth the effort of asking my sexton to assault it with his spade, either. For what will you find therein, other than gravel, disappointment or indeed worse?”

The younger man smiled gracefully, inclined his head as if by way of conciliation, and drained his own glass of claret. But although Mr Chambers was far too well-bred to contradict his patron, and indeed promptly sought to change the subject, as he did so, in the privacy of his thoughts he continued to wrestle with the mystery of the raised bank, its origins and what might lie beneath it. Mr Chambers, after all, had read Camden and Dugdale, Nicolson and Hearne, was a subscribing member of the local Gentleman’s Society, and had more than once attended a lecture at the Society of Antiquaries in Piccadilly. He believed devoutly that the past was a wholly intelligible place, if only the bright lights of enquiry, reason and logical argument could be made to shine persistently enough upon it.

In short, while the dissimulation was nicely done, the older man was a shrewd enough judge of human nature to know that dissimulation it was.

“Here, sir, fill my glass again, and fill your own, too. This projecting of yours is thirsty work. Well, the early days of December are a dull time, I admit of that, and the obscurity of my little parsonage a far cry from Oxford, let alone London, or indeed Calthorpe Hall in all its pomp and finery. I know that there is little enough to entertain you, save only the tithe audit frolick, and whatever we assay for Christmas. The weather is clement this year, and the ground not yet frozen. Shall we arrange” — and Mr Calthorpe pronounced the word as if it were some great curiosity in its own right — “an excavation?”

“I shall order it. Only when you decide to publish your record of it, and look around for subscribers, I shall be most affronted if you expect me to offer you a guinea, too.”

So the thing was decided, vastly to Mr Chamber’s satisfaction.

* * *

They made quite a handsome little party, gathered around the far end of the raised bank — the end that stood furthest from the parsonage, that is, for the other end of it, after it had run all along the back of the ancient building, had been buttressed with a strong flint wall at some time in the past century, if not before.

There was the sexton with his spade, his efforts reinforced by those of two young fellows from the village, none of them unaware of Mr Calthorpe’s notoriously generous tips. Mr Calthorpe’s curate was present, although he did little besides looking short-sighted and vaguely anxious.

There was also, of course, the Rev Mr Calthorpe himself, a portly and deliberate figure in his well-cut black clerical dress and old-fashioned wig, and the young Rev Mr Chambers, active and vital, who had brought with him paper and pencils for taking notes and making sketches.

At a distance, pretending they were engaged in useful activity, were several servants from the parsonage, clucking like hens with foreboding and disapproval, all of which they relished enormously. Even the redoutable Mrs Fulcher, who had kept house for the bachelor Mr Calthorpe for decades, repeatedly found excuses — not least, reproaching the other servants for their idleness — for standing out on the lawn to the south of the rectory, from which was afforded a particularly clear view of the end of the bank.

Next to the site of the excavation stood the Rev Mr Barnstable, incumbent rector of the adjoining parish, alongside Mrs Barnstable, and the couple’s only child and heiress, the clever and handsome Miss Honoria Barnstable.

I regret to report to you, but must in all honesty do so, that Mr Calthorpe did not notably relish the company of Mr Barnstable, whom he thought dull and censorious, any more than Mr Barnstable relished the company of his neighbour, whom he regarded as conceited, whimsical and profligate. Yet what avails a drama with no audience? Also, it must be said that Mr Calthorpe knew very well that Mr Barnstable, for all his defects, held, for reasons related to his own familial connections, a degree of sway in the disposition of several local livings, hence might be of some use in the practical business of Mr Chambers’ future advancement.

Finally — for how should we ignore the principal character in this drama before us? — there was the raised bank itself.

Mr Calthorpe’s living was set hard by the sea, in the country of Norfolk, on a spit of land facing out into the German Ocean. The bulk of the little town huddled around the quay or lined a single narrow avenue, quaintly titled “The Street”, that ran up from the industrious and squalid quayside to the top of the hill, at the crest of which stood the town’s ancient church. Mr Calthorpe’s parsonage, a largely unreformed warren of dark, unfashionably low-ceilinged rooms, lay on the lea side of the hill. So now you know how all that lies, which will save you the effort of consulting a gazetteer.

The raised bank, which ran directly behind the parsonage, the two of them aligned north-south, was perhaps fifty feet long and fifteen feet high. Further to the south and the west ran Mr Calthorpe’s glebe — up to the point where it ran up against Mr Barnstable’s glebe. Mr Calthorpe’s living was, by some distance, the more valuable of the two.

The party had dined early, at 1 pm. A couple of capons, a bit of brisket in a butter sauce of Mrs Fulcher’s own devising, a dish of grape tarts and a bottle of madeira worked their predictable magic in soothing Mr Calthorpe’s temper, casting a gentle glow of amiability over the arrangements. Under such circumstances he found the injunction to love his neighbour less onerous than was usually the case.

Mr Chambers, in contrast, felt himself almost too excited to eat. In his mind — wherein, during those salad days of his youth, he seemed to spend no small moiety of his existence — he was already draughting the lecture that he would deliver before a party of the most learned and august antiquaries extant, who would immediately welcome him into their number as the kindred soul he so obviously was, were they but sensible of his perspicacity, wit and sundry other signal qualities, with which I do not propose to tax you here.

So it was, at any rate, that soon after the clock in the hall struck 2 pm, the party gathered round in a bank, assaying conversation amid the sharp report of steel on flint, of stony earth flung to one side or the other, all illuminated by the weak wintery light of the low December sun.

At first there was only, as Mr Calthorpe had predicted, a great deal of gravel. The piles of spoil increased. By 2.30 pm, the gravel stood as high as the sexton’s waist, although it might be objected in this regard that the sexton, in common with many on this part of the coast, was not in the way of being a mighty man.

Mr Calthorpe called for a flagon of beer to encourage the diggers, and brandy for the gentlemen. Miss Barnstable and her mother sufficed with punch of unknown merit, supplemented periodically by the curate’s shy attempts at wit, more well-intentioned than well-received.

The digging resumed. A fabulously-inclined observer might have assumed from the scene confronting him that some vast monster had suddenly reared up, opened its jaws, and torn a bite from the side of the bank. The structure of the bank was becoming clearer — gravel and sea-flints at the centre, earth and turf nearer the surface. The sexton wondered, aloud, whether it had been dug in some part before. At any rate, it was man-made, clearly — but by whom?

The minutes ticked past. Brandy notwithstanding, as the shadows lengthened, Mr Calthorpe’s earlier bonhomie began to cool. He disagreed with Mr Barnstable about a minor point of liturgical propriety, and said so. Mrs Barnstable sent a boy inside to fetch a warmer shawl. Miss Barnstable’s pretty face, cheeks reddened by the fresh air, was unreadable.

The clock in the hall struck 4 pm.

It was then that Mr Chambers’ voice rent the mild air: “Stop! Pray, stop at once!”

The party ran to look, as Mr Chambers fell to the earth and began scratching at it himself, first with a spade and then with his own bare, long-fingered hands.

“’Tis a coin!” he said, extracting from a strangely fox-red patch of soil a small disc of metal, rubbing it with his sleeve so that its surface, otherwise dull and leaden, returned just a little of the fast-dying light.

Unfortunately, a close inspection of the area around the coin — because the whole party was scrabbling about in the hole now, trampling the dirt, picking up bits of stone and throwing then down again — revealed little of moment, save a few fragments of what might have been cloth that fell away to nothing as soon as Mrs Barnstable tried to retrieve them, and some rotten splinters of wood — or at least he assumed they were of wood — extracted by the curate who, when he could interest no one in them, decided they were of no merit, shrugged, and threw them away again.

Mr Chambers, of course, would have liked to have examined the site more thoroughly and systematically himself — to have drawn it, to have made notes — but try though he might, within the boundaries of good manners and taking account of his own very junior standing, it proved impossibly to halt the melee.

After that, it was far too dark to remain outdoors any longer.

There followed a general retreat into the parsonage, and a simple repast of pies, nuts, some cheeses, a cold fowl, russets and jelly before the great fire in the parson’s parlour. If the excavation was not exactly deemed a triumph — or so reflected Mr Chambers, preoccupied, stooping to retrieve Miss Barnstable’s fallen glove for her — neither had it been an absolute failure. On the morrow he would resume his excavation and discover what lay in the greater bulk of that bank, and thus claim his rightful place amongst the immortals of the investigative and antiquarian sciences.

* * *

It was a signal misfortune, then, that the weather, which had up to that point held almost unnaturally clear and mild for early December, took a sudden turn for the worse. The blue skies and gentle southerlies of recent days were changed in the night for an icy, insistent rain bearing in from the northwest, which looked set to last — or so Mr Calthorpe’s gardener, who had a cousin who knew these things in his bones, opined to anyone who would listen — until the New Year at the very least.

It was clearly impossible, while the rain fell, to continue the excavation.

There was a day when the rain lessened somewhat, on which Mr Chambers had high hopes that, come the morrow, with Mr Calthorpe’s permission, the digging might resume. This scheme, however, was thwarted by the news that the sexton had taken ill overnight, so much so that could not rise from his bed.

Mr Calthorpe sent the sexton a bit of boiled mutton, a flagon of Rhenish wine, a small phial of Venice treacle, sea coal, and warm wishes for a prompt recovery.

“We must all pray that no one dies this fortnight next,” Mr Calthorpe opined to his cousin, “for surely that unseasonably warm weather has played havoc with everyone’s humours! Did the curate tell you that those two boys whom you set to work on your excavating are abed with some pretended malady or other? At this rate, if the Devil decides to come for that old Ezekiel Rudd between now and Twelfth Night, you and I shall be out with our spades, finding him his long home.”

At this, Mr Chambers smiled weakly, and agreed that the previous warm weather had indeed been quite unseasonable, hence perhaps even more upsetting to the humours than this incessant, unwelcome rain, and expressed other similarly relevant and becoming sentiments, and returned to his reading.

In truth, though, Mr Chambers could think of nothing else besides what might repose underneath the rest of that raised bank. Since the day of the excavation, he had dreamed of that bank, slept restlessly, and awakened unrefreshed.

Increasingly, although he was not at first sensible of this, his trouble was more than one of mere thwarted ambition. No, it was a trouble buried far deeper than that.

The bank preoccupied Mr Chambers at table, sport and — I regret to report — at his prayers, too. No book, be it ever so droll or rich in pathos, so enlightening in its wisdom nor curious in its novelties, could divert him so completely that within a few pages, his mind had not wandered back to that hole, the gravel, whatever lay under and beneath.

Indeed, in his sleep Mr Chambers more than once apprehended that the bank, which lay directly beneath his bedroom window, was somehow alive, pulsing with a sort of unwholesome excitement, writhing silently yet forcefully in the velvety depths of the midwinter dark. These thoughts troubled him. He sought but failed to discern any rational explanation for them.

But he told Mr Calthorpe none of this — and in his great curtained bed in the larger and warmer chamber adjoining, Mr Calthorpe himself slept, as he generally did, the sleep of the righteous and well-fed.

Soon, however, the rain returned. It hammered down on the many variously-tiled roof-slopes of the rectory more furiously than ever.

When we next meet our protagonists — the two clergymen, older and younger — night had once again fallen. Mr Calthorpe and Mr Chambers were again in the old parlour, where a great fire had been made up for them, and the claret jug was once in frequent deployment.

It being that time of the year, Mr Calthorpe was interrogating his tithe accounts, which he kept in a massive bound ledger, where his own spidery, old-fashioned hand was interspersed, to rather displeasing effect, with the tidier, copybook efforts of his curate. Mr Calthorpe, unlike some, had no particular joy in the keeping accounts. He was, however, a conscientious man who sought to order the affairs of his own little kingdom to the best of his abilities, which were considerable.

Mr Chambers, meanwhile, turned the pages of a recently-published treatise on electricity, while at the same time his thoughts turned the gravels and damp earth of the bank, both these occupations to equally little purpose.

Outside, the wind was roaring and wailing, pulling at the roof tiles and the window casements. Once or twice, or so it seemed to Mr Calthorpe, there was sort of crashing sound, so loud as to startle even Mr Chambers from his reverie — no doubt, the consequence of the storm that raged so violently without.

In due course, Mr Calthorpe, having scrutinised the tithe ledger for some considerable time, making little notes on a scrap of paper and crossing then out again, had cause to want the curate, so he rang the little brass bell that sat on his desk for use in those occasions where he would summon someone to do his bidding.

Mr Calthorpe, being a clergyman of the old-fashioned sort, kept an almost excessively large household. Never was there any shortage of his people who might be expected to answer the call of the bell. Yet on this night, at least, it seemed that the parson rang in vain. He repeated his action, with a similar lack of effect. By this point, the novelty of the situation had occurred even to Mr Chambers, who had put down his book and his glass.

“Would you have me go, sir, and run your errand for you? Who is it that you would call?”

“I want that deuce of a curate, or at any rate someone to fetch him for me. His sums are all wrong! Also he has conflated Old Tibby Bishop with Old Toddy Bishop, would you credit it? Where is he, anyways? Was he at dinner?”

Mr Chambers evinced surprise. “I thought he was away with you, sir, in Holt?”

“Oh no, why should I want that fool in Holt? No, he was here, was he not?”

“Let me go to the kitchen and find Mrs Fulcher, sir, for if anyone holds the key to this mystery and indeed all other mysteries, it is she.”

But in that very instant, as Mr Chambers was rising to leave the room, there was another crash, strong enough to rattle the glasses and agitate the claret in the jug. The two clergymen regarded each other with alarm. So it was that Mrs Fulcher, clutching her apron, found the two of them when, uncharacteristically breathless and flushed, she rushed into the room.

“Oh Mr Calthorpe, sir, do forgive me, but there is such a state of affairs in the kitchen, I hardly know where to start, sir” — these were her ominous words of introduction.

“Where’s my curate, Bess? And what is that infernal crashing sound?”

“Beggin’ your pardon, sir, you don’t understand, sir! We were in the kitchen, me and the girl” — here, she was alluding to the maid who helped her with the cooking — “scourin’ the plates from dinner, and makin’ a start on your supper, when there was ever such a howlin’ at the kitchen door, and at first we made out it were the wind, but the wind weren’t out of the north, it were out of the north west, which is a clean different thing, so how could it have been the wind, sir? And then it was as if there was someone a-knockin’, a-hammerin’ on the door. So I took a fright, in case it was that Jeremy Leake who don’t agree with you over that tithe for Old Woman’s Meadow, and him in his cups and all, perhaps he come a-mischief making, this being the time of year that it is, and all? But up went the girl, right to the door — and she a little thing too, nor with any strength about her, which comes of her bein’ a Dines, them all bein’ small folk, you know, Sir?”

Mr Calthorpe and Mr Chambers nodded, transfixed, for Mrs Fulcher was in normal circumstances a stolid widow of notable dignity, phlegm and very few words. It struck them both that this change in her boded nothing to the good.

“So the girl, that little thing, she went right to the kitchen door, and she opened it. And the wind came in, and the rain came in, and the night was a-howlin’ like a demon all around us.

“At the door there was a tall man, Sir, with a long, dark cloak, and something pulled up over his head, but it weren’t ever Jeremy Leake, I knew that at once —”

Mr Calthorpe felt called to impose some sort of order on these proceedings.

“Ah, he was no doubt a beggar, Mrs Fulcher! For in these days before Christmas, why should a poor man not come to the door of any house and seek a bit of charity? Is that not a good and godly thing, Mrs Fulcher? I hope you gave our poor brother in Christ a penny?”

“Well, Sir, such is indeed a good and godly thing, and at the start I thought as you did, Sir — not least when he held out a hand, or what looked like a hand — for I reached in my pocket and fetched out a penny and gave it to the girl, and she reached out, for to offer it to him —”

Mrs Fulcher seemed overwhelmed. Wordlessly, Mr Calthorpe filled a glass with claret and offered it to her. She took it, blindly, and, after draining it, wiping her lips on her apron with shaking hands, she resumed her narrative.

“The girl reached out, Sir, and the man reached out too, but when he saw what it was, sir, he raised his head, and there was such a terrible sound —”

Mrs Fulcher looked meaningfully at the claret jug, but by this point, both men were unable to stir from the spot, so amazed were they aty her narrative.

“Well, I don’t know what happened, then, because I covered my face, and the door slammed shut again, so that the whole house shook with it — you gentlemen must have heard it even here in the parlour, did you not? — and the poor girl was a-lyin’ on the floor, she was, white as were a corse, and everything in the kitchen was knocked about and spoilt, and what am I to do now, sir? I laid the girl on the bench and tried to make her take some of your brandy, sir, and at that she perked up just a modicum, sir, and now she’s a-sittin’ by the fire, sir, but I can get no more sense out of her than I could out of the kitchen cat, sir, so what am I to do now? All the kitchen is knocked about and spoilt, and there’s a terrible smell, sir, like a rotting thing, like a dead thing, sir, what was blown in from the night. So I should like to know, how am I supposed to fetch your supper with all of that?”

Mr Calthorpe had seen a great deal of the world in his many decades of life. Like Mr Chambers, he had been at Oxford. What is more, with his brother, in his youth he had assayed the Grand Tour. Before he chose to retire to a rural living, albeit a very rich rural living, he was no stranger to Court, to lofty and learned circles, nor indeed (or so I have been told, although it may be mere hearsay) to those who enquire after things which they perhaps should not.

The cumulative effect of these experiences had impressed upon Mr Calthorpe the absolute primacy of some very simple things: manners, tradition, degree — order. Even in this, admittedly, Mr Calthorpe remained more latitudinarian than doctrinaire, such being his innately generous and kindly nature. Yet he was not prepared to countenance an irruption of chaos into his domestic sphere, and it was the consciousness of this, rather than anything more base, that framed his reply.

“That is all very well, Mrs Fulcher, and I am sure you will manage admirably. I rang, however, for another purpose. Might I trouble you for news of my curate? I have it in mind now that I have not seen him since we supped here last night.”

‘Did you not know, sir? Gracious, what a day this has been! That curate of yours had been lying abed in his chamber, sir, since before you left for Holt market, and me and the girl have been bringin’ him his victuals, not that he can keep naught down, either, he’s that disordered, sir. Fever? No, I think not, sir — his forehead is cold and clammy, though he sweats a fair bit — a foul sweat, rank, with some savour of earth about it — not at all a good sweat. No, what taxes me is that he’s disordered in his reason, sir. When ere he speaks, it’s only to say that ‘I don’t have it, I don’t have it’ — nor do I know what the ‘it’ is, either, sir — or as if he was a-fightin’ something off, flailin’ at it with his hands.

“Might you come and say a prayer over him, sir, if you have a moment? And the girl too, sir? Surely a prayer would do them both no harm?”

* * *

For a certain sort of farmer in Mr Calthorpe’s parish, the tithe audit frolick was, beyond all question, the chief ornament of the social year.

Already, many rectors — not least those who, like Mr Calthorpe, were men of consequence — had, after much effort, discovered excuses for jettisoning that ancient custom, buying off their tenants instead with gifts of choice comestibles or drink, all of these to be enjoyed, it was most devoutly hoped, at a safe distance from the rectory itself.

The anxiety therein was not simply one of cost. Not every rector, now, welcomed these hours of familiar proximity, not only with the greater farmers of the parish, but with the lesser ones, too — their conversation, manners and jests being still more rustic than genteel, and not invariably fit for polite society. Yet it was typical of Mr Calthorpe that, having inherited from his predecessors this custom, carried on since the memory of man knoweth not to the contrary, the parson should wish to retain the custom, burnish it, and indeed seek to pass it on in good order to his own eventual successor.

There were, however, you will perhaps not be surprised to learn, limits to Mr Calthorpe’s condescension.

On the occasion of the tithe audit frolick, Mr Calthorpe took his supper in the hall with the greater farmers, accompanied by Mr Chambers. Under normal circumstances, his curate would have presided over the lesser sort, seated on forms around a table in the kitchen.

The curate, however — despite Mr Calthorpe’s prayers, Mrs Fulcher’s remedies and the expensive if ineffectual interventions of a surgeon called out from Holt —remained indisposed. So it was that the parish clerk and Mrs Fulcher’s brother, also one of the rector’s tenants, were assigned the duty of keeping order there in his stead.

Dutch Poynter had, in his youth, served in His Majesty’s forces. Common fame had it that, even now, he being no longer in his first youth, he could lift his smaller contemporaries above his head and whirl them round about. Village competitions of strength had long since presented laurels to two categories of victors — Dutch Poynter, and whoever came second to him. If Dutch Poynter feared any living creature, it was his elder sister, Mrs Fulcher. So it was that Mr Calthorpe rested easy in his choice of lieutenant.

The tithe audit, you will be pleased to learn, passed harmlessly enough. The Rev Mr Calthorpe took it seated at the end of a long table set in the near the fireside in the hall, flanked by his clerk on one side and on the by Mr Chambers, to whom, I am sorry to report, a good night’s sleep still remained a stranger.

In front of those three were arrayed a good proportion of his tenants, the greater farmers to the fore, the lesser ones squeezed in behind, supplementing with their rustic savour, redolent of farmyard and patient industry, the air of woodsmoke, great age and solemn purpose that otherwise filled the room, as the hard rain, which had been falling for more than a week now, struck the leaded windows and made free with the chimneys above, howling and crying.

You may well wish to enquire why the parsonage of such a wealthy living — for such it was, and long had been — was set out in such an archaic manner, with low-beamed ceilings and meagre window-glass, the better rooms hung with dark old likenesses of grim-faced predecessors, so many little service rooms all so badly lit and appointed, rather than constructed in the more modern taste.

You are not, I vouch, the first to ask this. For indeed Lord Calthorpe, patron of the living, would often sport with his brother, saying “Fie, fat Harry, shall I not tear down that stinking old dog-kennel of a parsonage of yours, and build you up a new one? We can draw it up together — truly, Vitruvius himself will rub his eyes in wonder at the great stateliness and ingenuity of our design! What about it, brother?”

But although Mr Calthorpe’s parsonage was not of the latest fashion, having been coaxed into being in the time of King Henry VIII, if not before — for I must admit that here, concerning the whole history of the place, no living man knew the truth of it — and in some ways very incommodious, being dark and low and entirely lacking in the qualities normally associated with a gentleman-parson’s seat — Mr Calthorpe would allow his elder brother and patron to do no more than alter one single thing, which was to relocate the front door a few yards to the south, in order to give the place a little more symmetry of the sort prized by the best architectural geniuses of ancient Greece and of Rome — and also, it must be said, to add a better larder, but that only to please Mrs Fulcher.

“I am sparing you an expense, Jemmy!” Mr Calthorpe would reply to his brother. “Not all of us are so profligate as to waste ourselves mending that which requires no amendment.”

So it was that the parsonage remained unchanged, unfashionable and familiar, as Mr Calthorpe preferred all things.

You wax impatient! But this is Christmas, which is not a time for counting each of the minutes of the clock like some busy accountant, but rather a time for rambles, fireside tales and harmless diversions. And so it is that I shall counsel you, friend, to be less busy and more happily subject to the spirit of this, the season of our Saviour’s birth.

Back, then, to the tithe audit, which was soon concluded, since Mr Calthorpe had taken his usual pains to ensure that the men had all paid their tithes beforehand, so that any disputation of equity, or indeed appeals to the parson’s well-rehearsed generosity, might be carried out off stage, as it were, rather than before a critical first-night audience.

The accounts were settled. The clock in the hall struck 3 pm. Mr Calthorpe, with a stately deliberation and great formality, shut up his great ledger, set quill to one side, and pushed back his chair. “Sirs, I think we are done,” he said, in genial tone. “Shall we dine?”

There, to the general relief of all, commenced the frolick. The farmers took their seats along the long, low benches that had been drawn up for them. Before a full minute had passed, the table in the hall was well supplied with wine, brandy and punch, while in the kitchen, jugs of Mrs Fulcher’s own spiced beer were marshalled for the occasion.

As with so much in rustic affairs, the frolick had its own familiar course, well-anticipated and familiar to all those present.

Which is to say, as was usual, the party started cool, with some of younger farmers in particular a little over-awed by the company, studying their plates and napkins as one of the more confident souls opined how the wild weather was causing havoc amongst the livestock these last few days, so that even the calmest nags were wild and ungovernable, while another put it down to the beggars who appeared out of nowhere in this Christmas season, whom still another said must surely be foreigners come up out of Holt or such, or maybe even Norwich — places, admittedly, to which any manner of evil might readily be assigned.

But as the dinner itself began to appear on the two long tables, the one in the hall and the other in the kitchen, and libations were poured to the presiding spirits of hospitality — Mrs Fulcher’s strong spiced beer receiving particular acclaim — the company heated up considerably.

Mr Calthorpe was known to keep a generous table. One by one, the great platters came out — a boiled leg of mutton with capers, salt fish, plum puddings, boiled rabbits with onion, tripe, a great pie, eels, and finally a roasted sirloin of beef, to which the party generally raised a great toast — these, at least, are the dishes I recall, but doubtless Mr Calthorpe’s geniality and Mrs Fulcher’s skill ensured that there were many others beside which perchance escape my recollection.

Old Blind Bob from the quayside, who played upon the fiddle, had been lured up to the parsonage house with the promise of a shiny sixpence fee, so that first the hall, then the kitchen, echoed with his merry tunes, hard though they were to hear above the raised voices, the singing and hilarity, and of course the howling of the wind as it clawed at the doors and tore at the casements, howling and screaming, almost as if were a lost soul seeking entry yet being denied what it sought.

Even Mr Chambers, who in recent days had presented himself — or so it seemed to Mr Calthorpe — increasingly pale and preoccupied — for he was always glancing over his shoulder or sitting up late with a candle burning, and no longer seemed to find anything to please him in his books or learned treatises, sent up from London — at long last seemed to give himself up wholly to the merriment of the season, singing idle songs and downing bumpers with the best of them.

Mr Calthorpe raised a toast to his Majesty the King (and if anyone called out “which king would that be, then?” they did so quietly enough that Mr Calthorpe could feign not to hear them), the greatest of the farmers raised a toast to Mr Calthorpe which was avidly taken up by the company, and then all drank a toast to Mrs Fulcher, the sirloin of beef, and a great many other light and frivolous jests besides, which it would weary you to hear repeated here in this my narrative, so I shall omit them, being less insensible to your impatience than you might imagine.

If, at several points, there were crashing sounds to be heard in the kitchen, no one in the hall paid them much mind, so certain was Mr Calthorpe in particular, glass of port firmly in hand, that whatever was taking place there, it was nothing that Dutch Poynter and his sister could not, betwixt the two of them both, adequately address.

Fights, of course, sometimes broke out at the frolick — plates and jugs were broken — wild words were spoken, the rules of general decorum and felicity jettisoned after the seventh pint or so, tempers inflamed by drink, the warmth of the fires and high spirits of the season.

This, however, rather than being a defect, was indeed the great purpose of the frolick — or so it seemed to Mr Calthorpe, in those moments when he reflected on it — to bring all discord to the surface, so that it could be swept away with the rubbish and broken earthenware next morning, and the New Year could begin on a fresh new footing. That was why the drink flowed so free, the songs were so loud and often so coarse, too, and why no one cared that the dinner which began at 2 pm was often still in full spate at 11 pm.

Neighbourly goodwill is, after all, confected in many different ways. Minister of the Gospel though he was, Mr Calthorpe counted the frolick, at least in this very limited and specific regard, no less necessary and beneficial than the Holy Sacrament he would administer to these very same men on Christmas day, less than a fortnight hence. Each, in its own way, made things right again. The circle of the year would not have gone round in the same way without them both.

But then there was another crash, really too loud this time to be ignored — loud enough to silence the men in the hall, who regarded at each other in astonishment, and then at Mr Calthorpe, who stared in the direction of the kitchen, like the residue of the company, listening for what would happen next.

What happened, after an interval, was that Blind Bob appeared at the door, fiddle hanging sadly from one hand, waving his bow with the other, in some state of agitation. “Parson” said he to the room in general, “Mr Parson, begging your pardon, sir — the kitchen — pray, sir, come quick —”

Mr Calthorpe rose, with something more than his usual deliberation, and the company rose with him. They all filed through, or as many as could, although as the way to the kitchen involved passing through the dark and cluttered buttery, in truth many got no further than this, and had to crane and climb upon casks and crowd next to each other to see what was happening up ahead.

When Mr Calthorpe arrived in the kitchen, the nature of the scene before him was not encouraging.

The door to the courtyard stood plain open, so that the wind and rain were blowing in across the floor, scattering napkins, cloths and much besides across the pamments beneath. Nor was anyone still seated at the long table that ran, with forms lining each side of it, the length of the great long kitchen.

No, the bulk of the kitchen party was huddled together in the corner of the room set farthest from the courtyard door, apparently careless of the tumbled glasses, the spilled spiced beer, the bench that had been knocked down onto the floor (the old clerk was still sprawled across it, unable to rise to his feet) — the terrible smell of cold dank earth that had suddenly filled the room, so affecting in its stench that Mr Calthorpe found himself covering his face with the napkin he still carried in his hand.

To the front of the party cowering in the corner was Dutch Poynter. Yet even the indefatigable Dutch seemed to have fallen into some sort of swoon, and was more supported by the others than protecting them — his face pale as a winding sheet, his wide-open eyes still fixed on that empty, terrible doorway — although there was nothing there now but the wind, the corybantic rain, and that clammy, chthonic, unbearable stench.

Mrs Fulcher, for her part, was nowhere to be seen.

Mr Calthorpe, I must here note, was no more brave than any other man. Unlike some, however, he held fast to the notion that the best way to make others brave, in those moments where such was requisite, was to offer them a little spectacle of courage, as if by way of suggestion. So it was that he stepped cautiously across the wet and filthy kitchen floor, reached the door, and, with some effort, eventually managed to push it shut — although for a while, at least, it seemed as if more than a natural wind opposed him.

The door now closed, Mr Calthorpe composed himself. He turned back towards the company in the corner, some of whom were now rubbing their eyes or even spitting, there on the very floor, as if to purge themselves of a foulness.

Mr Calthorpe, for all his geniality, had a fine temper, and the events of the past minute had done much to enflame it.

“Well? Poynter? What is the meaning of this devilry? Are all of you dumb dogs, now you’ve drunk my beer and eaten my beef, and made a sty of this, my own kitchen? Poynter? Speak up, man!”

But instead of Dutch Poynter, who was still hardly able to stand, let alone speak, it was Blind Bob who replied to the the parson.

“Sir, we thought he were a beggar! This being the frolick and that, half the country knows of it, and knows you keep a generous table too, sir, if you’ll forgive me for saying it. So when we heard that knockin’ on the door, we thought it were some brave soul coming askin’ for some beer and a penny, it being that season, sir. That was what we thought —”

“Well, why didn’t you simply give the poor wretch some beer and a penny then, Bob, and send him off on his way?” interrupted Mr Calthorpe, impatiently. “ Why — why all this?”

“The gentlemen, they sent me to answer the door, sir. It were for a sport, we all being quite merry and that — they liked it that Blind Bob should have a few sporting words with this beggar, a bit of wit, sir, before the beggar had his dole.

“So I went and I found the door, and I opened it right up. And there were someone there — well, I can’t see with my eyes, sir, as you know to be the case, but like most blind folk, I know full well if there’s a man standing right before me — I can hear it, like, or feel it in the air, or summat. And there was someone there before me — a tall man, I have it in mind, though how I know that, sir, I couldn’t tell you.

“So I had some sport with him, Blind Bob did, how forward he was coming here, this were a party for gentlemen, perhaps we could spare him a ha’penny — I were waving it about before him, this old bent ha’penny — oh, you know the sort of sport I mean, do you not? I am sure you do know, sir. It is a very prevalent kind of mirth, at least here amongst the ordinary folk.

“But after a little time I could hear that the gentlemen at the table had all gone quiet, sir, and the room were cold as ice, the wind was like nothing I’ve ever known in my life, and there were that — that smell, like an open grave,sSir! Well, I didn’t like that smell. You don’t know how bad it were, either, sir — it’s most of it gone away now, believe it or not, but it were ferocious when it started. And what’s more, there were something about the beggar before me that I didn’t quite like, though I cannot tell you how it was that it sat wrong with me, sir — only that it did.

“So I took fright, and I’m sorry for it, sir, and for making sport of — whatever it were, there at the door, because I know you keep a generous table, and we are all bound to love our neighbour as ourselves, sir, as you told us many a time, and I remember well all that you’ve told us, so if I did bring this upon you, sir, I most humbly beg your pardon for it.”

Mr Calthorpe’s anger, being that kind which is far more easily stirred than enduring, had receded now. In its place was a kind of weary curiosity. “Never you mind, Bob,” he replied. “I know your wit well enough, and I do not think it can have been the cause of — this, whatever it is. Poynter, man, can you really supply no elaboration on Blind Bob’s tale?”

But it was impossible to get any sense out of Dutch Poynter, or indeed out of the other men, except the most rudimentary, monosyllabic verifications of Blind Bob’s report. Here is the meat of it: there had been someone at the door, Bob had teased him then offered him a coin — and that was all they could say.

Although it was hardly gone 10.30 in the evening, and there was still wine and beer yet to drink, it was clear that the frolick was done. One by one or two by two, bashful, quiet,stripped clean of all their earlier hilarity, the farmers started to make their way back, through the inky dark, along rain-lashed lanes and wind-blasted byways, to the safety of their own cottages, hearths and families.

Mr Chambers, it should be said, had been near enough the vanguard of the hall party as to hear and see most of Mr Calthorpe’s interrogations. It was curious, then, that the young man seemed, if anything, less shaken by this turn of events than did the rest of those present. It was almost as if he had somehow anticipated it. His mind, in those days ever restless and questing, laboured away on secret suppositions, although he said nothing. Nor was his silence in any way remarked upon, given the general uproar.

Mr Calthorpe, meanwhile, restricted himself to matters of practical import.

“There is one thing I don’t understand, Bob. Where is my Mrs Fulcher? Was she not serving the gentlemen their dinner?”

Bob, who had taken his evening’s wages from Mr Calthorpe — wrapped in a screw of old paper, so that the blind man didn’t yet realise that what he held was no sixpence, but in fact an entire shilling — had been about to leave, too. He turned back towards the parson.

“Indeed she was, sir — and it was a generous and lavish repast that she served up too, sir, and the company were that grateful for it! You do keep a generous table, sir, there is no mistaking that.

“But just before — before that — that knocking at the door — we could all hear the curate upstairs, sir, in his sickbed. He were banging on the floor and making such a racket — wailing, sir, like as if he was a child! — that Mrs Fulcher, she went upstairs to sit with him, and to see how the girl was faring too, that was also sick abed.

“I reckon, sir, that had Mrs Fulcher been down here, that — that thing at the door — well, he’d never have been so bold, would he, sir? I reckon he wouldn’t have dared.”

* * *

The weeks passed, but no matter how Mr Calthorpe’s gardener looked at the sky or how often Mr Chambers tapped his fingers on the barometer, the weather held to the wet and stormy, so that all the folk said, whenever they met, whether at their duties or indeed in the inns and ale-shops of the Quay and the High Street, that there had never in all creation been such a sorry and inclement December, with the roads in such a state now and so many falling ill, and the animals all out of sorts, and those beggars and idle folk up from Norwich causing so much mischief, too, and who ever heard of such a Christmas? All of this pleased them, of course, for country folk are never more gratified than by some catastrophe.

Christmas passed, at least for the Rev Mr Calthorpe and his young cousin the Rev Mr Chambers, much as it always did, on those occasions when Mr Calthorpe was in his parish, rather than at Calthorpe Hall.

Which is to say that Christmas dinner — rather than being taken in a grand dining room lined with mirrors, blazing candles and great pictures after the French or Italian manner, accompanied by well-coiffed ladies robed in the finest silks and gentlemen of fine wit, prodigious learning and great political weightiness — was instead kept in the parsonage hall, low and dark, in the company of a dozen of the poorest and most ancient fellows from the village, in the little space left between prayers with Holy Communion in the morning, and more prayers in the afternoon.

Mr Calthorpe, at least, seemed to find no hardship in this. He was of that old species of parson who could remember the name of Old Ned’s late wife, gone these last twenty years, who did not mind that as much food fell out of Old Clay’s toothless and rancid maw as ever stayed put in it, and who found Old Gabber Johnson’s single piece of wit a source of great hilarity and wonder not just that first time Old Gabber declaimed it, but every other single time that Old Gabber repeated it, too.

Old Ezekiel Rudd, so cosily settled on the threshold of the hereafter as to be deemed unable to make his way to the parsonage, was sent his dinner — sack, capon, tripe, mince pies — in a basket, with 6d. hidden away at the bottom. And all the old men known to have wives, children or anyone else waiting for them at home were given baskets to take away, too.

Much other festivity transpired, a little of which I shall adumbrate here.

Lord Calthorpe sent up a cart from London, laden down with presents for the parsonage household: a new shotgun for Mr Calthorpe, a discarded old suit of superb black silk from which Mr Chambers might have a new coat cut, a piece of Flanders lace for Mrs Fulcher, oranges and lemons, cinnamon, cloves, a little telescope that could fit in a gentleman’s pocket, playing cards, and, fresh off the press, a very scurrilous libel indeed on William Pulteney, which amused Mr Calthorpe enormously but seemed hardly to divert Mr Chambers at all.

In return, Mr Calthorpe filled the cart with pheasants, geese, ducks, woodcock, plovers, snipe, barrels of oysters, as well as a quantity of jenevers and rum upon which, his being a sea-facing parish blessed with many obscure creeks and moorings, duty might or might not have been fairly paid — Mr Calthorpe was, it must be said, uncharacteristically vague on that matter.

Even the widow of Mr Calthorpe’s non-Juring predecessor, who still lived at Cley, although now very ancient, was sent a box of sugared almonds, and in return provided Mr Calthorpe with a jar of cherries in a syrup, together with a handful of yellowed old pamphlets. Truly, the season of goodwill was at hand.

Meanwhile Mrs Fulcher’s condign rage, at its zenith a fair match for that of her employer Mr Calthorpe, had long since abated. History does not record whether she entirely believed the tale told to her by Mr Calthorpe touching on the devastation and ruin of her kitchen. Experience, however, had long since taught her that men, left to themselves for any amount of time, generally make a great mess of things. It was only the smell that now and then rekindled her wrath, for despite her very best efforts, scrubbing with vinegar and ash and other remedies known only to herself, now and then it would return, chiefly at night, and when the winds came out of the north.

Indeed, relations were soon positive enough that by the time that Old Year’s Night drew near, Mr Calthorpe who, for all his genial misanthropy, was at heart a convivial soul, propose a little party.

“You’ve had a dull enough time of it here, dear cousin,” he opined to Mr Chambers. “That blasted frolick, your Christmas dinner taken amid a cabal of drooling dotards, and all the while, the rain never stops — so strange for the north coast of Norfolk, too! Is it any wonder that half the village folk have taken to their beds, or seem addled in their wits — more so, even, than is usually the case? Or that the animals are all falling ill, and only idle strangers seem bold to walk abroad?”

In truth, Mr Calthorpe was uneasy about Mr Chambers. Did the young man, too, have, in some part, this increasingly ubiquitous winter malady?

Most of the time, to be sure, Mr Chambers played a positive figure in the life of the house — insisting on taking upon himself, for instance, some of the duties of the poor curate, still lying sick abed — duties he carried out with due diligence and seriousness. But if he stayed up very late now, as indeed he often did, it was not to play at cards, or to read the news sheets or novels sent up from London — increasingly, it was to study old books of theology that he discovered on the shelves of Mr Calthorpe’s library, his own prayer book, or even the Bible itself.

Now and again, Mr Calthorpe would espy the younger man standing at the parlour window, which overlooked the raised bank — indeed the site of the excavation itself — watching (as Mr Calthorpe took it) the weather outside. But when he saw that he was the object of Mr Calthorpe’s attention, Mr Chambers would turn away, pale and preoccupied, his fingers fiddling with something that he would thrust back swiftly into the inner pocket of his frockcoat. Then he would beg Mr Calthorpe’s pardon, and make light of the thing with a pleasing Latin epigram, or similar — and all would seem well again, until the next time that the very same thing happened, sometimes as little as an hour or two later.

Mr Chambers, you will surely intuit from this, no longer dreamed of offering a lecture in front of the Society of Antiquaries in grand rooms in Piccadilly. His dreams, now, were of another sort.

This, then, is why Mr Calthorpe made the suggestion which I shall report to you forthwith, as I can see you are once again fidgeting and waxing impatient with this Christmas tale of mine, in a hurry to be somewhere else, as if our lives did not hasten on quickly enough, whether we like it or not.

“This old year is limping off stage, sir, spavined and sad, and we shall not miss it,” declared Mr Calthorpe one morning to Mr Chambers. “All the more reason that we should bid it farewell in company. Shall we have that pompous fool Barnstable and his pretty daughter again? I am told that Mistress Barnstable is, alas, still ill with the palsy, but perhaps they have other folk staying as well? Let us see the New Year in with good cheer!”

Mr Chambers welcomed his cousin’s suggestion, all the more so as he found himself, in these dark days of winter, happier in company — any natural human company whatsoever — than otherwise.

So it was that as dusk — a wet and stormy one, as was ever the case that Christmas season — fell on the last day of the year, a small but merry party settled around the table in the ancient parsonage hall, under the low oak beams dressed with holly and ivy, with a great log burning in the massive fireplace, for all the world as if it had been 1541 and not 1741, with old King Harry seated on the throne, and not his Majesty King George II.

At the head of the table, which is to say at the end nearest the parlour, for we must be particular about these matters, sat Mr Calthorpe. The party over which he presided included Mr Barnstable, Barnstable’s unmarried sister (well advanced in years, but far more lively and agreeable than her perpetually disapproving brother), the fair Honoria his daughter (wearing a sky blue silk robe with fur trimming that suited her very well, or so at least was Mr Chambers’ considered opinion), and of course Mr Chambers himself.

Mr Chambers sat to Mr Calthorpe’s right — chivalrously, on the side of the room further away from the great fire. Honoria Barnstable was seated directly across from him, next to her aunt. Mr Barnstable sat to Mr Chamber’s right. The table, not that it matters greatly, was a smaller and better table than that which had been used for the frolick and was dressed with good linen, the benches replaced with chairs, in keeping with the more polite and genteel nature of the occasion, and Mr Calthorpe’s best silver candlesticks illuminating the scene, to what was agreed by all to be a most pleasing effect.

Mrs Fulcher, the sad circumstance of her kitchen girl’s continuing indisposition notwithstanding, had outdone herself, for the great dishes sent through from the kitchen contained potatoes, peas, a roast turkey-cock, apple pie, cod with an oyster sauce, knuckle of veal, plum puddings dressed with holly and set aflame with brandy, fried eel, a blancmange, a cauliflower, and sundry things besides, so that even strait-faced Mr Barnstable had to admit that the dinner was an uncommonly fine one.

Once again, under the spell of his jug of claret, the fine comestibles and the spirit of the season, Mr Calthorpe found himself sensible of a greater tolerance for his neighbour Mr Barnstable, whose dour features and disapproving look had been in some measure softened by the cheerful scene unfolding around him. Similarly, Mr Barnstable regarded his neighbour Mr Calthorpe with greater latitude, and for a brief moment found his high manner pleasing, rather than a sort of personal affront.

The younger Miss Barnstable, meanwhile, had noticed a portrait, very much after the fashion of King James I’s time, hanging on the dark-panelled wall behind Mr Chambers.

“Sir,” she enquired, playfully, “who is that very grim looking man behind you?”

Mr Chambers started, as if he had seen a ghost, but the rest of the company, it would seem, noticed nothing amiss.

“Ah, Miss Barnstable, that is one of my predecessors here, Mr Poynter by name,” replied Mr Calthorpe instead, when Mr Chambers failed to answer.

“Truly, I am glad that you are parson here, and not he,” said Miss Barnstable, “for he looks the very devil!”

“Really, daughter, I must ask you to show more courtesy towards the late Mr Poynter — know you not that you are his, what, his granddaughter, albeit at two or three removes?” Mr Barnstable, his mouth half full of cod, swallowed, and turned towards Mr Calthorpe, as if applying to him to settle the point.

At this, Mr Calthorpe looked astonished. “Barnstable, sir, I had no idea that you were of Poynter’s line!” he said. “I shall be more careful in future when I speak of that old rogue, wizard and cankered heretic.” And here he laughed heartily.

“Ah, but he’s no kin of mine, sir!” objected Mr Barnstable. “Did you truly not know that the Lowdes, my dear wife’s people — the Wiveton Lowdes, that is — are in some part descended from Poynter?”

“I knew no such thing, sir — only that our own Poytners, Mrs Fulcher’s people, are descended from some cousin of his. So your daughter and Mrs Fulcher, too, are cousins, then? Well, I congratulate them both!”

Under other circumstances Mr Barnstable might have risen to this, had not Mr Chambers, who had evidently been puzzling something out, intervened.

“Sir, do I recall rightly that you said, once when we were discoursing on the matter, that you thought it was your predecessor, this Mr Poynter, who raised that earthen bank?”

This time Mr Calthorpe paused a little before he replied, for it turns out that he was a circumspect man, as well as politic one. “I — I have been told that Poynter’s name is connected in some wise with that tedious and vastly over-analysed bank, but I really cannot, sir, recall much more than that. I thought he had constructed it, or involved himself with it in some wise. But perhaps I misremember.”

Miss Barnstable, for her part, was still admiring the portrait.

“What a dark, saturnine countenance he bears, my grandsire Poynter! I apprehend him glaring down at me, even as we speak! Well, we shall be merry despite him. Now, tell me a thing. You called my grandsire there a wizard and a heretic — what meant you, sir?”

“Ah, had I recalled to my aged and faltering mind that he was your grandsire, my dear, I should have spoken far more gently of him! Doubtless he had great qualities, did my predecessor, Mr Poynter. For I have certainly heard from many an authority that he was formidably learned and had a pretty wit, too.

“But surely we have tarried on these historical questions too long now, have we not? This is Old Year’s Night, my dear — out with the old, in with the new!”

“But a wizard, sir! Looking at his visage, I do not wonder he was called so, my grandsire! Was he really a heretic as well?”

Mr Calthorpe, it seemed, would say no more. But it happened that the elder Miss Barnstable could not resist the opportunity to advertise her own evidences in the case before them.

“What I have been told, child, by those old enough to have been told it by their own grandsires — for you know as well as I do what country people are like — is that Mr Poynter, having been the chaplain to some great personage who enquired into many things, many of them most unnatural and unholy, later continued these researches here, in this very place! And indeed some of the old folk say that Mr Poynter tried to raise the dead, and that this, not all the other things, is the true reason why the better folk here could not stomach him, and why his parishioners were not content to have him as their parson, and were glad when he died.”

At this, the younger Miss Barnstable’s eyes shone. “Would it not be a great thing, though,” she enquired, almost dreamily, addressing her words to no one in particular, “to raise the dead? Think of how much we might learn from them!”

“Enough, daughter!” exclaimed Mr Barnstable. “Do not speak so lightly of such things — your jest is not a pleasant one. If I have not found it meet to mention Mr Poynter to you before, it is some measure because his reputation is, in truth, not entirely benevolent. His was indeed an enquiring mind, but in some of his enquiries, he was driven more hotly by ambition — by pride, to put it bluntly — than by Our Lord’s teachings, which tack more towards humility and obedience.”

Mr Barnstable appealed to Mr Calthorpe, like some beleaguered captain on the field of battle seeking the swift arrival of reinforcements.

“Quite so,” interjected Mr Calthorpe, quickly. “Quite so! Just because it is possible to do a thing, does not mean the thing ought to be done — some things in particular. If his little flock, and indeed his greater neighbours, hated and feared him, theirs may have been the greater wisdom. He was, alas, not a good parson.

“But here, Mr Chambers — are you quite well? Sir, why are you become so pale?”

The entire party regarded Mr Chambers with concern. For a moment the young man said nothing, merely wiping his well-formed, clever, weary face with his napkin. But then he raised his glass in a slightly trembling hand, drained it, and forced a smile. “Truly, I am very well indeed, sir. Perhaps I have consumed my dinner too quickly, the repast being so remarkably delectable, so lavish and so varied, for there was a moment wherein I felt a little lightheaded. I assure you, though, that it has now passed.”

After that, a little silence descended upon the company. It was, in due course, the elder Miss Barnstable, Mr Barnstable’s voluble sister, who brought it to an end. Attempting to reignite the conversation, she addressed herself to Mr Chambers.

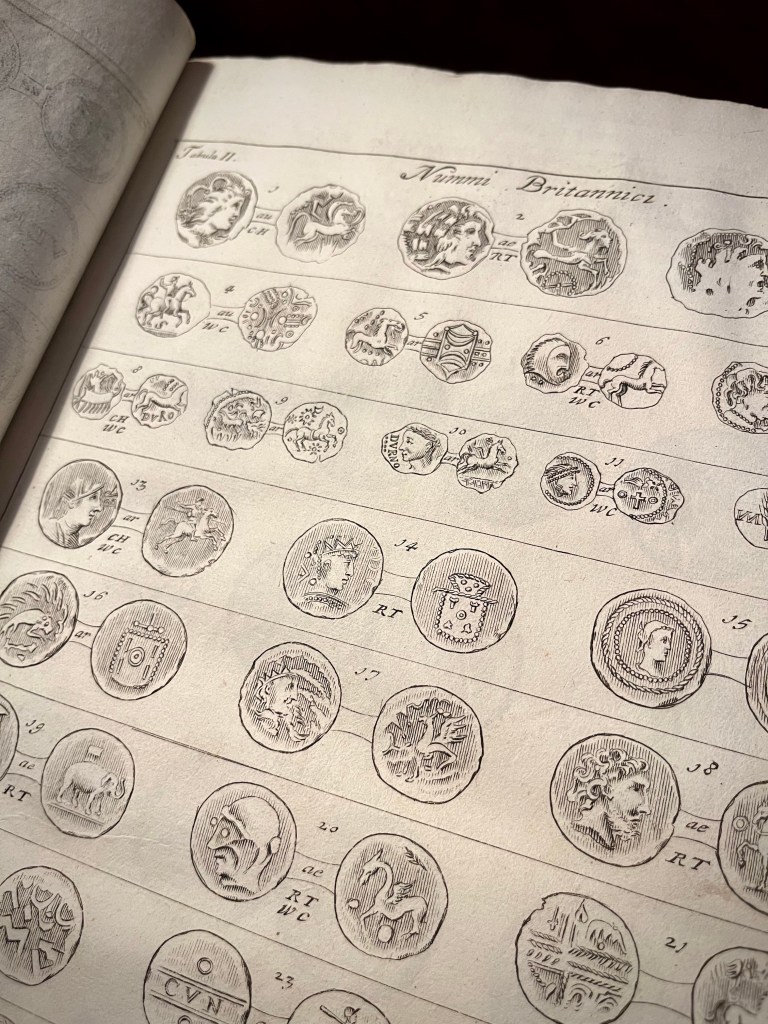

“Sir, my niece has regaled me often, since my arrival, with the story of your excavation here — indeed we have debated amongst ourselves often, have we not, dear Honoria, whether what you have uncovered here is perhaps the site of some great battle in which hundreds of Danes were slaughtered — or, perhaps, where the Danes made great slaughter, I am not certain which is more likely, are you, Honoria? — whether it is some fortification or other notable erection of Roman times, or indeed, perhaps a grave of some great personage who flourished here at some even earlier point, mayhaps some Britannic descendent of Brutus, whose people raised to him a great monument upon the occasion of his death?”

“Sister, I do not see how we shall ever know what passed between the time of the Flood and the arrival of the Romans, for surely no writings survive to us from those aeons?” objected Mr Barnstable, mildly. “If it were a pertinent thing, it would surely be written of in the Bible — or by, well, Josephus or Tacitus. Or some other authority.”

“You are both omitting the greater likelihood, dear neighbours, that my cousin has led us all upon what is sometimes called a wild goose chase, although in this case leaving us with no wild goose, which would have been a useful acquisition, but only with several heaps of wet gravel, currently defiling the great sanctity of my lawn and habitual place of perambulation.” This was Mr Calthorpe, leaning back in his chair, twiddling the stem of his glass between his fingers, fixing the elderly Miss Barnstable with a teasing look. “Should you not, my dear Miss Barnstable, consider that the raised bank might be, simply that — a raised bank — made by some poor parson here to stop the wind from the west blowing through his windows, or the village cattle trampling across his prized horticultural specimens?

“Oh, I know very well that some of my people tell strange tales about that raised bank, but this is not Oxford or London — the folk here are simple, credulous and easily excited by trifles, for what else is there to entertain them on a dark winter night, but tales of such? They quake at an old earthen bank! And yet an ordinary earthen bank it still must be. The farmers here are no better than those moon-struck scholars in Wales who would tell us that every lonely, decayed sheepfold is the ruins of some Druidical temple.

“Is it really the case that all ordinary things reward the busy-ness of scientific enquiry? Is it not enough that they are what they are, and we what we are, too?”

At this, the older Barnstables both smiled, and Mr Barnstable even thumped the table a little to signal his approval. Mr Chambers smiled too, after a moment, albeit weakly, hiding whatever unease he felt, and was on the brink of framing some suitably polite and light-hearted reply, when the younger Miss Barnstable, who was not laughing at all, her cheeks now very red, spoke up again, in absolute earnest.

“Sir! With the greatest respect for your superior learning and experience of the world, your age and your wisdom, are you certain that your raised bank is indeed so ordinary? We may, perhaps, for all we know, be surrounded by the extraordinary, which is only rendered dull and prosaic through the habit of our everyday acquaintance with it. Are you so certain that the raised bank might not, after all, be such as my dear aunt had just now suggested to you — a place that was once of great power and consequence?”

The elder Miss Barnstable saw her chance. “I know, because I have often read reports of it, for instance in the publications of the learned societies, that such earthen banks or mounds, when excavated, not infrequently reveal at their heart some entombment or burials, the bones still garnished with the fine trappings and insignia of the monarchs or warriors of older times. Would it not, then, when so many banks hide secrets, indeed be extraordinary if your bank were, as you claim it to be, of no interest at all?”

“Here is the thing that would settle it, though, would it not?” The younger Miss Barnstable turned her bright, flushed, fine-featured face towards Mr Chambers. “Did you discover aught, Mr Chambers, regarding that coin you found under the raised bank?”

It might be thought that the young clergyman, who had been stealing covert glances at Honoria Barnstable now and then throughout evening, might have been pleased that her attention had, once again, fallen so decisively in his direction. Yet the very opposite seemed to be the case — for he started, and blanched, and was again struck speechless, for all the world as if he had been caught out in some guilty secret.

“Come on, my good Sir,” called Mr Calthorpe, very much in jocular tone, mistaking, as did the others at the table, the cause of his his cousin’s discomfiture. “Our delightful critic is surely correct in this point, at the least. Let us see the wretched thing, will you not? I know you have it in your breast pocket — next to your heart.” And at this, the residue of the company smiled.

Mr Chambers swallowed deeply, wiped his face with his napkin. He looked around blindly, before finding his voice again. “Sir, the coin is a thing of no account — a very poor thing indeed,” he objected. “I will not trouble this company with it.”

“In what way is the coin poor, Mr Chambers?” pressed the younger Miss Barnstable. “Is the condition only poor, or do you mean the design itself? For it is a surely a well-known thing to numismatists, even the most unlearned and unworthy amongst us, that while, for an instance, the coins of the earlier Roman emperors may display the most remarkable artistry, it remains the case that some of those coins that came later — or before, even! — are sometimes the rarer, stranger, hence more rewarding? Or do you perhaps mean that the material is poor — that it is not, for an instance, made of pure gold? Yet similarly, we know that there were coins made of gold and silver alloy’d together, that are not to be scorned, duller though they might be in appearance?”

“Pray, let us see your coin, Sir!” exclaimed Miss Barnstable’s aunt, now thoroughly excited by the prospect. “We demand to see this coin!”

“Let us see the coin, man!”

“Show us the coin!”

The party had waxed, by this point, sufficiently lively (for indeed the clock in the hall would have been striking five, if it had not mysteriously stopped, despite having been wound properly that morning, not that any there present noticed it) as to be making between them all a great deal of noise, with Mr Calthorpe and Mr Barnstable banging the table and the two Miss Barnstables entreating with some passion, when all of a sudden, in a moment, the room was illuminated by a bolt of lightning, then promptly shaken by such a clap of thunder as to shake not only the window casements, candlesticks, plates and dishes, glasses and jugs, but the pictures on the walls, even the walls themselves.

The thunderclap had the effect of reducing the party, momentarily, to a stunned silence. Their ears rang, slightly deafened, while before their eyes hung the pale after-image of whatever they had fixed their gaze upon at the moment when the lighting had struck. In the case of Mr Calthorpe, this seemed to have been something just outside the window, for it will be remembered that his seat, unlike most at the table, commanded a view out towards the area that lay in front of the house — a neat little court, strewn with gravel — the shutters of the hall windows not having been closed up entirely that night. Looking out again, however, he could see only rain falling in sheets, caught in the light reflected out from the hall itself, and then darkness beyond.

Essaying to dispel the silence, Mr Barnstable ventured the following: “They do say, do they not, that a winter’s thunder is the world’s wonder?”

To which inanity Mr Calthorpe replied, wholly unsmiling, in a stern tone very uncharacteristic of him, “From lightning and tempest, good Lord deliver us!”

“Amen!” responded Mr Chambers. Perhaps because they were all in some manner still a bit deaf, his voice sounded louder than he had intended.

The aunt laughed nervously.

The only member of the company who appeared unmoved by these events was, in fact, Miss Barnstable.

Once more, she fixed her handsome, determined, unwavering gaze across the table on Mr Chambers, and addressed him directly. “Please, sir, although you might think such a thing prodigious in one of my sex, in truth your excavation has taken a place front and centre on the stage of my imagination. Indeed, as my aunt implied, I have thought of little else since that day, so many weeks ago now, on which it took place. For I do believe that what you have found must surely be the tomb of some ancient personage, from the times before the Romans held sway here — no ordinary personage, either, from the scale and majesty of the thing! And although my dear father thinks otherwise, it is my view that only through these sorts of enquiries that we will every truly learn the origins of our own line, that rejoices in the fine name of Briton! So I hope you will not consider it an impertinence, Sir, but have you not felt an inclination to dig the thing further — to get to the heart of the thing, as it were — to uncover the whole unarguable truth of it?”

Mr Chambers stared at her wordlessly, as he had been staring at her for many long moments now, so that her image seemed burned onto the organs of his senses, permanently imprinted there, although he was still unable to frame the words in which to reply to her — unable to speak at all, as if some sort of spell had been cast upon him.

Misunderstanding the reason for his silence, she beamed a beatific smile at him. “Apologies, Sir — how my chatter must tire a man of your learning and worldly experience! My parents, and indeed my dear aunt, often reproach me for being far too free with my words, so that in multiplying indefinitely, they soon come to possess, individually, only the most derisory value. Yet in a quiet place such as ours, with so little by way of society, and that so dull and provincial, I must confess that your excavation has awakened something in me, which is why I can hardly counsel myself to stay silent regarding it.

“Please, dear Sir, would you not show me your coin? We shall make a bargain — show me the coin and I shall trouble you no more with my silly womanly fancies! Please, sir — give me the coin!”

And with that, the younger Miss Barnstable held out her hand to him, across the table, palm upwards.

Mr Chambers thought to himself afterwards what a beautiful hand Miss Barnstable’s was — slim, long-fingered, perfectly-formed — and how he should have liked to have clasped it, and covered the narrow wrist beyond it with kisses — covered it with kisses all the way up to the white, silky crook of that elbow, and indeed, perhaps far beyond. But instead, there at the table, slowly, deliberately, he reached into the inner pocket of his black frockcoat, and found the coin.

At that point, someone knocked at the hall door.

As one, the party turned and stared at the door, which was on the opposite wall to the great fireplace, to which the long table was set in parallel.

It was an odd time, you will no doubt agree, if you have been patient enough to follow along with me thus far, for someone to knock at the hall door — well past dark, on such a stormy evening, on Old Year’s Night, too. There had been no sound of hooves approaching the parsonage, nor the step of someone arriving on foot. Anyone coming to visit Mr Calthorpe’s people, or on business or affairs of household management, would in any event have gone round to the kitchen door. It was also odd that none of Mr Calthorpe’s people had heard the knocking, and come to answer the door on their master’s behalf.

But there was something else about the knocking that silenced the greater part of the company, restraining them in their seats, still as statues, while Mr Calthorpe rose, slowly, from his seat at the head of the table — something wrong about the sound of it, as if what had knocked at the timber had been no normal, living, human hand.

Carefully, deliberately, Mr Calthorpe set down his napkin, adjusted his bands, and brushed a crumb from his black silk breeches. Slowly, purposefully, he made his way towards the door. He grasped the handle and turned it. He started to open the door.

The door opened inward into the room. Because of the way in which the rest of the party were seated — half of them looking back over their shoulders at Mr Calthorpe, the others looking forward, but with their view blocked both by the door and by the broad, black-clothed back of Mr Calthorpe himself — they could not see who was outside the door.

The temperature in the door seemed suddenly to drop. The older Miss Barnstable drew her shawl more closely around her and shivered.

Mr Calthorpe stood at the door for about half a minute, looking out into the night, as the room became colder and colder, and as the rest of the party became conscious of a terrible, dark, choking smell that had begun to fill their lungs. And then Mr Calthorpe turned back into the room, still holding the door open. He reached out a hand to Mr Chambers. His voice, when he spoke, was quiet, gentle — but also irresistible.

“Give me that damn’d coin, Chambers, you fool, and be quick about it.”

Chambers reached into his breast pocket, drew out the dull-coloured coin. Trembling, he slipped it into Mr Calthorpe’s hand.

The younger Miss Barnstable gave a little cry.

Mr Calthorpe turned back, reached out and handed the coin to someone — something — out there in the darkness. “I wish you the compliments of the season, sir,” he said. Then he made a bow, gently closed the door, and came back into the room.

Sitting down at his seat again, he picked up an orange — it was once of those that Lord Calthorpe had sent from Calthorpe Hall — and began, very deliberately, to peel it with a silver-handled knife, marked with the Calthorpe crest.

After a short time, Mr Chambers, his natural colour returning, found his voice. He attempted, not entirely successfully, a casual tone. “Who was that, Sir, to arrive so late, and to go without so much as a word?”

Mr Calthorpe paused for a moment before replying, perhaps because his concentration was so entirely trained on the project of peeling the orange. “Only a old neighbour, sir, who perchance would have something from us. So I gave him his due. For as our Lord and Saviour sayeth, ‘Give to him that asketh thee, and from him that would borrow of thee, turn not thou away.’ Surely that is only good counsel, sir, not least at the turning of the year?”

“Very good advice,” interjected Mr Barnstable, pouring himself a glass of port and sending the jug round to the left — and then pouring for Mr Chambers, when it became clear that he was still in some measure a little astonished.

“The best advice!” exclaimed the aunt, helping herself first to one walnut, and then to another.

“’Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night, nor for the arrow that flieth by day, nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness, nor for the destruction that wasteth at noonday’ — recall you that, sir, from the Psalms? I like that verse very much, too. Do you like that verse, Mr Chambers?”

This was Miss Barnstable, resting her pretty arms on the table, looking at Mr Chambers with something that was half amusement, half real concern. He caught her eye. The look that united them briefly did not go unnoticed by their elders, their glances meeting too. Their own smiles were quick to follow.

The savour of orange, sharp and bright, hung emphatic in the air.