Frank Auerbach: in memoriam

by Barendina Smedley

British painter Frank Auerbach has died, at the age of 93 years.

Whatever else they may have been, Auerbach’s pictures were never easy — easy to make, or easy to love. Effort was demanded on both sides.

First impressions of his work — on the part of critics and, indeed, the rest of us — often focused on the superficial. Auerbach’s paint could be almost ludicrously thick, his brushstrokes crude, the resulting accretions of pigment apparently messy, hard to read — rebarbative.

And yet, the longer one engaged with those violently rubbed-out charcoal drawings, those wildly stabbing orthogonals, the grossly clotted or savagely scraped-back surfaces of the paintings, the more they tended to offer in return.

There’s a famous photograph taken by John Deakin in 1963, showing Auerbach sitting at a table in Wheeler’s seafood restaurant in Soho. He’s flanked by figurative artists including Francis Bacon, Michael Andrews and Lucian Freud. This was a photo op, not an actual lunch — part of a scheme by RB Kitaj to will into being a “School of London” to rival the New York and Paris versions.

Yet Auerbach was never, in truth, a good fit with any wider movement. Insofar as he had colleagues, he learned a lot from his friend Leon Kossoff, just as he did with his bad-tempered, brilliant teacher David Bomberg. For a time, before they all fell out, Bacon and Freud shared criticism, conversation and quite a lot of drink. Bacon, though, died in 1992, followed by Freud in 2011 and Kossoff in 2019, leaving Auerbach to carry on alone with the serious practice of art.

For Auerbach, art was everything. It was an obsession. From the early 1950s onward, his life came to revolve around a daily routine of drawing and painting — a practice carried out with near liturgical regularity, day in and day out, without interruption or deviation except in the most exceptional circumstances.

Similarly, his early images of post-war London building sites apart, he operated within a very narrow, exclusively urban geographic range — Primrose Hill, Camden, his little 30” x 30” studio at Mornington Crescent. Until the bus services failed him, this also took in visits to the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square, where for decades he found company and inspiration amongst the Old Masters.

While his work might strike casual viewers as instinctive or expressionistic, Auerbach was entirely clear that art was, as he put it, a “cultured activity”, and that the Old Masters were there to “teach and to set standards”. Titian, Rembrandt, Vuillard and Soutine were influences, as were Giacometti and de Kooning, these latter two first encountered through black-and-white magazine illustrations. “I’ve been influenced by everyone,” he acknowledged in an FT interview with Jackie Wullschlager. “The past is the compost in which we grow.”

There was also something obsessive in his choice of subject-matter. He painted only what he knew and cared about. This included a strictly limited number of locations, and, when it came to portraits, an even more limited cast of sitters.

Although he did make portraits on an occasional basis — one thinks of his oddly delicate drawing of art critic Robert Hughes — in the end, Auerbach’s greatest portraits were those of a small group of friends, family and lovers who sat for him, regularly and religiously, sometimes for forty years or more. These included a former landlady and lover (Stella/EOW), his sometimes estranged wife (Julia), his son (Jake), and a handful of others. The resulting portraits document not only physical changes, but also — because, at its best, portraiture is a two-way transaction — changes in the temperature of Auerbach’s own relationships with these sitters.

Sitting for Auerbach was demanding. His was a distinctive creative process. At the start of his career, he’d rework his surfaces for months or even years, building up a crust of paint so dense, granular and thickly clotted that, in the end, it looked less like pigment than some sort of charred, organic substance. Sometimes he wouldn’t bother with a brush and would apply his paint straight from the tube.

Later, when he had more money, he’d simply scrape back his work each day and start anew, painting wet-into-wet, sometimes blotting the paint with crumpled newspaper, editing and obliterating, rolling the dice and staking everything on the outcome, until the moment where what he saw in the picture coincided, somehow, with what he was seeking.

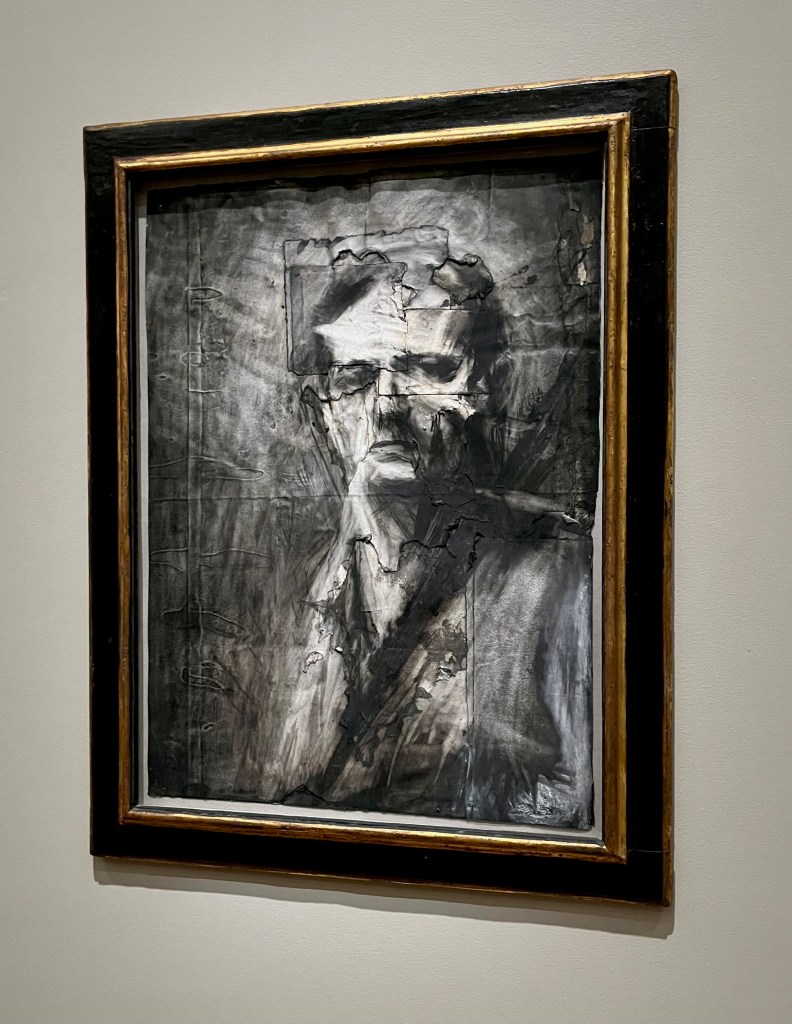

His drawings proceeded along similar lines. Working with charcoal, chalk and crayon on paper, he’d rub out the previous day’s effort. Often he did this with such raw fury that he broke through the surface of the paper. He’d then have to patch it from the back, leaving literal scars on the image.

When working, Auerbach might recite long passages of poetry (Yeats, Auden, George Barker), swear or sometimes shout. The finished works ended up freighted with all this — the passage of time, the rubbed-out missteps and failures, the evidence of their own inadequacies and precariousness. No wonder Auerbach’s sitters were invariably people who loved him, and believed in his work.

Yet Auerbach was also extremely intelligent, articulate and sensitive, not least when speaking about art. He could be kind, very funny — and, in a self-deprecating way, courageous. This is evident not only from his friend and longtime sitter Catherine Lampert’s Speaking and Painting (2015), but also from several documentary films produced by his son Jake Auerbach, eg FRANK (2015).

“I don’t keep anything. It may be due to my background. I absolutely believe that you keep forging on, forwards, and that if you look back you turn into a pillar of salt.”

Auerbach was born 1931 in Wilmersdorf, Berlin, Germany. His father, a lawyer descended from a long line of rabbis, had been decorated for his service in the Great War. In 1939, days before Auerbach’s eighth birthday, his parents sent him off to an experimental boarding school in Kent, later relocated to Shropshire.

In 1943, however, his parents’ Red Cross postcards stopped arriving. Max and Charlotte Auerbach had been murdered at Auschwitz.

Auerbach insisted, repeatedly, that these early losses hadn’t traumatised him. Nor did he define himself as a Jewish artist. Refusing to disavow his Judaism as long as antisemitism existed, he reiterated that “ritual and religion mean nothing to me”.

When, however, WG Sebald included in his novel Die Ausgewanderten (1992, translated into English as The Emigrants in 1996) a character evidently and outrageously based on Auerbach, complete with a wholly fictionalised experience of the Holocaust, Auerbach intervened, aggressively, possibly litigiously but certainly decisively.

Perhaps, then, Auerbach was not so much indifferent to his past, as unwilling to let someone else’s paraphrases of it define him. And if those obsessive habits of unmaking and remaking, the need to cocoon himself within a small circle of people and places he loved — even the desire to capture what he loved and render it immutable — constituted some kind of coping mechanism, then it was, at least, a richly productive one.

None of this held him back. After a shaky start (he worked in theatre for a while), his art career took off quickly. He had his first major show at the Beaux Arts Gallery in 1956, aged 24. Where lesser critics complained about the heaviness of the paint, David Sylvester spotted “fearlessness” and “profound originality”. So it was that when Kitaj postulated, however inaccurately, a “London School”, Auerbach’s centrality was unarguable. Bohemian in his domestic arrangements, unworldly, unapologetically intellectual, Auerbach had become, by the time he was in his 50s, a critical and commercial success.

Despite the continuities in his practice, Auerbach’s work changed considerably as the years passed. By the mid 1960s, having signed to Marlborough Fine Arts, with money flowing in from collectors and institutions, he could afford a greater range of colours, leaving behind the chthonic mud-pies of the 1950s to embrace first of all strong yellows and greens, then eventually in the early 2000s, a surprisingly candy-sweet range of pinks, mauves and pale blues. The move from thicker to thinner surfaces traded materiality for a new freshness. Oils gave way to acrylics.

Auerbach represented the UK at the Venice Biennale of 1986, and was given major retrospectives at the Royal Academy in 2001 and at Tate Britain in 2015.

His goals, though, never altered. Rather than simulating some quasi-photographic likeness, he was determined to capture the deeper reality of a particular situation, no matter how many tries and false starts it took, in order to give it permanent form.

There were reasons for this. As Auerbach said to Wullschlager, “in some curious way the practice of art and the awareness of the imminence of death are connected. Otherwise we would not find it necessary to do the work art finally does — to pin down something and take it out of time.”

He could be remarkably literal. Once, on a whim, I embarked on a mini-pilgrimage to Camden in order to track down the studio depicted so often in his drawings and paintings. It proved easy to find, for the simple reason that it did, in the end, look recognisably like his images of it.

Auerbach lived through an age that was sceptical about painting. His response was an old-fashioned, unwavering commitment to an inherited tradition, coupled with a very 20th century acknowledgement of that tradition’s fragility and limitations. His work was, at its best, a gesture of defiance against the impossibility of ever painting anything, of ever saving anything. It was also, in an era of cool ironic detachment, entirely serious.

Despite all the difficulties, what eventually drew me to Auerbach was precisely this seriousness. Of course his pictures can be beautiful within the logic of their own language, once one’s learned it. That’s the hard part, although well worth the effort.

More than that, though, I warmed to his persistence in the face of a probably doomed objective, of which the resulting physical image becomes a kind of a relic or talisman. His art remains ineradicable evidence of another human consciousness. It’s there for us to meet halfway, as one person gets to know another, with all the potential misunderstandings and epiphanies that suggests.

Although I heard Auerbach speak a few times, I met him only once.

In 2005 I was walking along Regent Street near Piccadilly Circus, pushing a pram, when I noticed someone staring at me. On a busy London street, a direct stare is rarely good news, so I looked right back at him — at this older man with a halo of greying hair, blunt features and dark, hooded eyes.

Other than the way in which he was staring at me, the most distinctive thing about this man was his bottle-green velvet jacket. Then the moment passed, and we went our separate ways.

Later, spotting a photo of Auerbach dressed in a bottle-green velvet jacket, I realised what had happened. Ever since, I’ve wondered about it. Had he been imagining, as he stared at me, how he’d draw me? Had he been framing my head in those violent, lavish, spectacularly confident vectors of colour, building up those layers of knowledge and speculation, only to scrape them all back and start again?

The encounter lasted only a few seconds, but I’ll never forget it. Intense, almost intimate in the connection it created, it offered me an insight, unique and precious, into how art happens — into how Auerbach’s own art happened.

I feel very grateful for it now.