Naming names: in search of Martha Moore

by Barendina Smedley

This is not a ghost story, at least not in any normal sense of that term. Nor is it much of a history. It answers no important questions. Nor does it make a satisfying progress from A to C, stopping smartly upon arrival, with B folded neatly into the middle.

Instead, what follows is an attempt to know something about a woman who bore the name Martha Moore. She was born in 1603 and died in 1669. She lived in various places, including but not limited to Norfolk.

I can tell you now that her story is not a remarkable one. She interests me, for various reasons, but I know for a fact that others find this sort of thing infinitely tedious. They may well be correct.

A few years ago, I wrote a story in which someone very like her plays a central role, which you can read here.

Yet because Martha Moore interests me, I have continued, ever since, to find out all I could about her — and, having done so, it seemed wrong simply to close away my notes, such as they were, forever. To quote (as I’m well aware that I do far too often) a favourite passage from an essay by one of Martha Moore’s near-contemporaries, Sir Thomas Browne, in his Hydriotaphia: Urn-Burial; or, a Discourse of the Sepulchral Urns Lately Found in Norfolk,

We were hinted by the occasion, not catched the opportunity to write of old things, or intrude upon the antiquary. We are coldly drawn unto discourses of antiquities, who have scarce time before us to comprehend new things, or make out learned novelties. But seeing they arose, as they lay almost in silence among us, at least in short account suddenly passed over, we were very unwilling they should die again, and be buried twice among us.

This is exactly what I feel about the various scattered fragments I’ve gathered together while looking for Martha Moore.

Here, then, for what it’s worth, is an attempt to piece together her story.

* * *

Let us consider the parish church of Wiggenhall St Germans, a little village four miles south of the port of King’s Lynn.

Wiggenhall St Germans is in Norfolk, but it straddles the Great Ouse, a large and at that point strongly tidal river. West of the Great Ouse are the parishes of Freebridge Marshland. The “free bridge” stood, and stands, in Wiggenhall St Germans — unlike the ferry service that also conveyed people across the river from at least the 13th century onward, there was, at least at an early point, no charge for it.

Marshland, in turn, was previously a vast, flat, mysterious realm of what might were they not saline, casually be termed fens. Reclaimed by drainage projects in the 17th century, the area is now composed mostly of arable farms and nondescript hamlets.

Until the 1950s, Marshland flooded frequently and catastrophically. Perhaps it will again.

The parish church of Wiggenhall St Germans, with its graceful little tower and decayed brick porch, perches just east of the river bank, a good eight feet or so below the normal high tide mark of the river.

Although located in Norfolk, it’s part of the diocese of Ely. As with most Church of England churches in the area, it’s the community’s deep memory expressed in physical form: a pleasingly unconsidered jumble of absolutely first-rate late medieval bench ends, stairs winding up towards a rood loft that hasn’t existed for almost half a millennium, raunchy mass-market paperbacks sold four-for-£1 in aid of the church fabric, and a light-soaked chapel where veneration of St Thomas of Canterbury has now given way to a pragmatic little galley kitchen suitable for sustaining long meetings on the part of the PCC. This is a village that used to be extremely prosperous and rather self-important, but that is now peripheral, friendly and, often, apparently slightly sleepy. I don’t get the sense that anyone minds this very much.

We will pass by the book stall, the table carefully stocked with informative leaflets, those bench ends with their entirely recognisable depictions of the Seven Deadly Sins enacted in the gaping mouths of large fish, and — as the PCC meeting commences in the chapel next door — make our way into the relative dark of the chancel.

Here, amid other ledger slabs, more or less elegantly incised, we find what we are seeking. There’s one slab that’s less slate grey than a kind of dirty brindle. It bears no date. The inscription, in slightly naive lettering, is as follows:

“Here under lyeth interyed Mys Martha Jackson and her two children.”

This, then, is where Martha Moore is buried, and where her story ended — under a stone that explicitly, and indeed very intentionally, fails to name names.

* * *

To discover where Martha Moore’s story began, we need to visit another church. It’s the church of All Saints just above the Albert Bridge in central London — a church better known today as Chelsea Old Church.

Chelsea Old Church, although also located next to a tidal river, is rather a contrast with the parish church at Wiggenhall St Germans. For one thing, Chelsea Old Church has a large palm tree in front of it, and a little sunken garden next door containing, inter alia, an unfinished sculpture by Sir Jacob Epstein. The flow of traffic along the Chelsea Embankment is more evident than the quieter current of the nearby Thames.

Chelsea Old Church has its origins in the 12th century, when Chelsea was still very much — rather like Wiggenhall St Germans, as far as that goes — a wealthy little village upstream from a thriving sea port.

On 14 April 1941, however, the church was struck by a German parachute mine. The tower and much of the nave were obliterated. The two chapels flanking the chancel survived in slightly better order, the southern-most one in particular. After the war, happily, the church was rebuilt, the chapels and monuments pieced back together to the greatest extent possible, and the whole reconsecrated in 1958 in the presence of HM The Queen Mother.

If we can find the church unlocked — “the church will be open from 2pm to 4pm Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday”, according to the parish website — then what interests us here is the north chapel.

From at least the fifteenth century, these chapels belonged not to the parish, as was the case at Wiggenhall St Germans, but rather to private families. This is why the northern-most chapel at Chelsea Old Church is called, to this day, the Lawrence Chapel.

The first of these Lawrences was Thomas Lawrence. Born in 1539, he had risen from modest Shropshire origins to become a successful “goldsmith” — probably less a craftsman than what we’d now consider a banker and merchant adventurer. By 1583 Thomas Lawrence was able to buy what a slightly run-down yet still prestigious medieval manor house, built in timber and with about four acres of land accompanying it, just to the north and east of Chelsea Old Church. With this came rights over that north-facing chapel. In the year of his death, he was granted a coat of arms.

So although in 1590 Thomas Lawrence further acquired a manor house at Delafords in Iver, Buckinghamshire, — as with any Tudor “new man” the urge to secure a country seat for his heir was a strong one — in death, which came for him in 1593, he chose to be memorialised in his new family chapel in Chelsea.

Thomas Lawrence’s marble monument survives to this day. Two groups of carved figures kneel, facing each other, under a magnificent display of arms, including those of the Goldsmiths’ and Merchant Adventurers’ companies. Here is Thomas Lawrence’s farewell message, directed frankly to us across the ages:

The yeares wherin I liv’d weare fifty fowre

October twentye eight did end my life

children five of eleven, God left in store

sole comfort of theyr mother & my wife.

The world can say what I have bin before

what I am now examples still are rife

Thus Thomas Larrance spekes to tymes ensuing

that death is sure & tyme is past renuing.

To which one can only reply that this is unarguably true — if arguably a bit bleak in tone. But then, well it might be. Randall Davies, in a parish history written in 1904, would blithely dismiss the family thus: “Such are the records of the Lawrence s of Chelsea, a family remarkable for neither wealth, nor descent, nor any exceptional merit.”

Back, anyway, to the business at hand. As the monument states, only five of Thomas Lawrence’s eleven children children survived infancy. These included his daughter Martha Lawrence, born in 1583, who probably took her name from that of her mother, Martha Cage. The youngest, Sarah Lawrence (c. 1591 -1631) married in 1613 Richard Colvile (1588-1650) of Newton Hall, just outside Wisbech in Cambridgeshire. The eldest son, Thomas, named after his father, hanged himself in his own London home at the age of 25 years, meaning that his brother John inherited the bulk of Thomas Lawrence’s estate. Martha would, in the end, outlive her various siblings.

But this is getting ahead of ourselves. Martha Lawrence was about ten years old when her father died. On 12 January 1602, when she was about 19 years old, she married William Jackson at St Mary Aldermary on Bow Lane in the City of London. And this, in turn, explains the “Mys Martha Jackson” named on that ledger slab at Wiggenhall St Germans.

* * *

William Jackson was an aspiring politician. We know literally nothing about where he came from, who his parents were, whether he had any sort of education — although much later in this journey, I may try to posit a theory about this. In any event, a suit in Chancery later documented that by 1601 — immediately before he married Martha Lawrence — Jackson was already a member of parliament as well as receiver general, or as he styled himself, ‘secretary’ to Charles Howard, first earl of Nottingham.

Nottingham, for his part, was many things — a cousin of Elizabeth I, courtier, diplomat, privy council member, patron of the arts and theatre, and, perhaps most famously, the admiral who, inter alia, commanded the English forces during the defeat of the Spanish Armada. He was present at Queen Elizabeth’s deathbed and Lord High Steward at the coronation of James I. He was, in short, a powerful ally for any ambitious young man.

Proximity to Nottingham allowed Jackson to be elected as member of parliament for Guildford in 1601, to carry a canopy at the coronation of James I in 1603, and then to be elected as member of parliament for Haslemere in 1604.

Only a year after Martha Lawrence married William Jackson, she gave birth to the first of their two children. Martha Jackson was born in Chelsea on 22 May 1603. Later, she would be joined by a brother, William.

Arriving in this world soon after the death of Elizabeth I and two months before the coronation of James I — her father a member of parliament and well-connected at court, her mother wealthy and also well-connected within the City of London and Chelsea — young Martha’s prospects must have looked very bright indeed.

Very soon thereafter, however, William Jackson’s all-important relationship with the earl of Nottingham began to go wrong. Let us hear what the article about him on the History of Parliament website has to say about this:

In May 1604 Jackson shared in a grant of lands in Derbyshire and Leicestershire, made at Nottingham’s request. Shortly afterwards, according to his widow’s later account, Jackson became bound ‘for necessaries to furnish his embassage into Spain and for other uses’ in sums amounting to over £3,000, ‘and for his indemnity he relied only upon his lordship’s promise’. Nottingham offered him either £200 a year from the wine licences or £400 a year on the more hazardous revenue of the Irish customs; but neither came to anything, and Jackson agreed to accept, in satisfaction of two-thirds of the money, a conveyance of his master’s lease of the Surrey rectory of Dorking for three lives, agreeing to buy out a reversionary interest for £633. However, this deal also fell through and his debts forced Jackson to leave Nottingham’s employment and ‘hide his head and to suffer executions to come against him, his goods and lands’. He brought the Chancery suit in 1620 to oblige his former employer to take a reconveyance of the rectory and provide better security. He also became embroiled with Nottingham’s widowed daughter-in-law and her servant Henry Lovell, but in a counter-suit he was charged with embezzlement. He had been living in the suburban parish of Bermondsey for at least two years when he died intestate in November 1623, before the matter was settled. Administration of his estate was granted to his widow [Martha Jackson née Lawrence], who exhibited a further Chancery bill against Nottingham in the following year. The outcome of the case is unknown.

Whatever else Martha Jackson might have hoped to inherit, then, she grew up in the shadow of a complicated, protracted and unpleasant legal dispute, which by 1638 also involved other family members. Her father had died when she was only about 20 year old, his career in ruins.

Her mother, a widow, was left to pick up the pieces.

* * *

We are back now at Wiggenhall St Germans, standing on the bank next to the church, watching how quickly the tide runs out, baring as it does so a widening brick-red, crinkled scar of mud all along the reed-lined edges of the channel.

The clock in the tower of the parish church is chiming the quarter — an oddly delicate yet resonant sound. The clock was installed in 1897, in celebration of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, funded by a public subscription of £120.

The chime sounds, I think, through a mechanism causing something to strike against one of the old church bells. Four of these remain. The oldest bell dates, remarkably, from 1499. The youngest is from 1882. Two more date from 1618 and 1630 respectively. The frame in which they hang was made in about 1624, although the arrangement that allows clock to chime, calling out each quarter with cheerful regularity, has also of course rendered the full peel of bells mute — completely unringable.

There was, at any rate, quite clearly some sort of campaign going on in the 1618-30 to improve the peel of bells at St Germans. Indeed the bell that dates from 1630 was probably funded, at least in part, by a £5 bequest from Thomas Moore the elder of that same parish.

A yeoman farmer, Moore had made his will in June 1630. In the way of these things, although it was almost certainly written for him by someone else — either his son or the village curate — it probably does give us a glimpse of him.

Thomas Moore seems to have been relatively traditional in matters of religion — stating that he trusted to be saved only by Christ’s merits (a formula used by Catholics as well as protestants) then scheduling bequests for “the feast of St Michael tharchangel” and “the feast of thassumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary”. The curate who witnessed his will for him, William Trendle, was styled “Sir” — an almost pre-reformation flourish, that.

Thomas Moore wished to be remembered by those amongst whom he had lived. To the poor of St Germans, and also the next-door parish of Wiggenhall St Mary, he left a dole of 30 shillings and 36 bushels of coal to be given for three years in a row, at the feast of St Thomas the Apostle (i.e. 21 December); the poor of the other two Wiggenhall parishes, Wiggenhall St Peter and Wiggenhall Magdalene, were to be given a similar dole of 10 shillings.

From this, we can probably assume that Thomas Moore owned property in all these four parishes. He had ten godsons, each of whom was to receive 3s 4d. Other friends and relations — Tuddenhams, Pattricks, Gardners — were left modest bequests of a few pounds each, yet there were quite a few of them, too. These sums add up. He must have left something like £70 in cash bequests, which was not a trivial amount of money, although in a different league altogether from Thomas Lawrence’s son John, who, only a few years later, was leaving each of his many children something like £900 each.

No, the overall impression left by Thomas Moore the elder is that he was a solid example of what his contemporaries might have called the “middling sort” — a man of no particular social pretensions, not highly educated and by no means a gentleman, yet comfortable and respected in his community — something to which all those god children also attest.

And then there was that £5 to be paid towards the purchase of the “grete bell” for the parish church. Thomas Moore asked to be buried in the churchyard of Wiggenhall St Germans, which these days is filled with far more recent graves, all from the nineteenth century onward. Nothing was said anywhere about a monument. Perhaps that didn’t matter to old Thomas Moore. The bell, at least, has survived. Perhaps we somehow hear his voice in that.

* * *

Thomas Moore the elder had a son.

Because the parish registers only begin in 1600, it is hard to know much about the history of the Moore family in the parish. In the late 16th century, they don’t seem to be mentioned in other people’s wills or in legal disputes — at least not in any I’ve seen. Perhaps they were relatively recent arrivals.

In 1600, however, in Wiggenhall St Germans, Thomas Moore the elder had married Dorothy Clark. The younger Thomas Moore was born in St Germans in January 1602/3 — the same year in which Martha Jackson was born. He seems to have been his parents’ only surviving child.

Somehow this yeoman farmer’s son began to acquire an education, although we have no record of how this took place.

When Thomas was nine years old, he and his neighbours experienced a catastrophe of that must have been remembered in the area for decades afterwards. This is a near contemporary account quoted in Richard Williams’ History of Kings Lynn:

“On the Feast-Day of All Saints, being the first of November in the year of our Lord 1613, late in the night, the sea broke in through the violence of a North East wind, meeting with a Spring Tide, and overflowed all Marshland, with the town of Wisbeche, both on the north side and on the south; and almost the whole Hundred round about; to the great danger of men’s lives, and the loss of some; besides the exceeding great loss which these counties sustained through the breach of the banks, and spoil of corn, cattle, and housing, which could not be estimated.”

But in fact the losses were indeed quite rapidly estimated, not least because they affected the ability of the inhabitants to pay tax and other duties.

In December 1613, the extent of damage locally was claimed as follows:

Terrington: £10,416

Walpole: £3,000

West Walton £850

Walsoken: £1,328

Emneth: £150

Wigenhale and South Lynn: £6,000

Tilney and Islington: £4,380

Clenchwarton: £6,000

West and North Lynn: £4,000

In all: £35,834

Marshland had quite a history of disastrous floods. The children of the village must have grown up hearing stories of catastrophic inundations. The Bible verses about Noah and the Great Flood most memorably displayed on a board in the church at West Walton must have seemed very real to them. There was another bad flood in 1618. People who lived in Marshland must have become very well accustomed to rebuilding homes, businesses and lives on a fairly regular basis.

But there were also different kinds of dramas that must have had some impact on Thomas Moore’s childhood. St Germans, as we have seen, was only four miles south of King’s Lynn. It’s hard to imagine that villagers didn’t travel that short distance for business, to take advantage of market day, or simply to enjoy the various attractions of this lively, wealthy and in some sense fairly cosmopolitan town.

On 12 January 1616, a few days after Thomas Moore’s 13th birthday, Mary Smith of Lynn was hanged for witchcraft in bad weather in front of a large crowd. The town preacher of King’s Lynn who was also rector of West Lynn, Alexander Roberts, even wrote a book about it: A treatise of witchcraft Wherein sundry propositions are laid downe, plainely discovering the wickednesse of that damnable art … With a true narration of the witchcrafts which Mary Smith, wife of Henry Smith glover, did practise: of her contract vocally made between the Deuill and her, in solemne termes, by whose meanes she hurt sundry persons whom she envied [etc]. (There is a good account of this sad affair here.) With hindsight, Smith was all too clearly simply a woman with strong and outspoken views about things, who must have annoyed her neighbours and lacked the social capital to protect herself from the consequences.

Nor was this the only evidence of potentially fractured communities to balance against the wholesome picture conjured up in the will of Thomas Moore the elder.

We have seen that Thomas Moore left bequests not only to the poor of Wiggenhall St Germans, but also to the other Wiggenhall parishes — notably Wiggenhall St Mary. This latter parish was, and is, a small place, very much centered on the hall. Indeed it probably started life as a chapel for the hall’s residents. From the 13th century until the 17th century, the family that lived in that hall, dominating the life of the parish, were the Kerviles. The Kerviles had been early and resolute supporters of Queen Mary; once Queen Elizabeth was on the throne, they promptly slipped into Roman Catholic recusancy. In this, their resolve was strengthened by their connections with other strongly Catholic families — in particular, the Bedingfields of Oxburgh, the Sulyards of Wetherden, and the Pierrepoints of Holme Pierrepont.

In 1604, a list of “Jesuits that lurk in England” included a “Mr. Pierpoint” lurking “with Mr Karvyle in Norfolk”. This was almost certainly Gervais Pierrepoint. Henry Kervile (d. 1614) had married Winifred Clifton née Thorold, the widow of George Clifton (d. 1587); Gervais Pierrepont was George Clifton’s half-brother. This was probably the same Gervais Pierrepoint who escorted Edmund Campion (1540-1581) through several stages of his mission to England in 1580 — a fact which opens up the fascinating possibility that Campion, who under questioning was careful to hide the identities of most of his contacts, might have visited the Wiggenhall parishes a few decades before the younger Moore’s birth.

Even during the youth of Thomas Moore the younger, however, the Kerviles’ recusancy must have been a significant local talking-point. In 1620 some fairly colourful accusations were levelled at Henry Kervile’s son, another Henry. There had apparently been a meeting of “papists”, who

are as forward to help the [Holy Roman] Emperor as others are to contribute to the King of Bohemia, to which end there were within three weeks about thirty of the greatest note assembled at Mr. Carvill’s in Marshland, and there rated themselves and other at a liberal proportion […]

Inevitably, Henry Kervile was arrested, and St Mary’s Hall searched. Kervile was released after his wife (Mary Plowden, from another well-known recusant famly) paid a bond of £2,000. In the end his accuser backtracked, after which Kervile made a very public statement of loyalty and was knighted before the year was done. And then in 1624, when Thomas Moore was about 21 years old, Henry Kervile died. His two young children, a little girl and an infant boy, had predeceased him. The girl was named Mary — the boy, Gervaise.

In the mid 18th century the Rev Mr Charles Parkin described Sir Henry Kervile’s tomb and its context in the church of Wiggenhall St Mary as follows:

This east part is divided from the other part, by an oaken screen, and was an old chapel; here is a stately altar monument of marble and alabaster, whereon lie the effigies of a man in armour, and his lady in alabaster, resting their heads on cushions, with their hands in a supplicant posture; below them is the pourtraiture of a little girl, with her hands conjoined, and by her, a boy in swaddling cloaths; on one side of them is Kervill’s arms, gules, a chevron, or, between three leopards faces, argent, impaling azure, a fess indented, in chief, two lis’s, or, Plowden;—on the other side Kervil impaling Lovell, of Barton.—On the west end Kervile impaling sable, three bars, sable, over all, a bend ermin, Fincham; and Kervill impaling sable, three covered cups, argent, Boteler, or Butler.—At the east end Kervill, and Plowden in single shields. (fn. 4) On this stand 4 marble pilasters of the Corinthian order, with their capitals gilt with gold, supporting an entablature of the same; on the summit is a goat passant, sable, attired or; the crest of Kervill, and his arms as above.

On a black marble wall-piece this inscription:

Hic deponitur corpus Henricj Kervilj, equitis aurati, filij et hœredis Henricj Kervillj Armig. de Winefredâ conjuge suâ Antonij Thorold militis, filiâ procreati; uxorem duxit Mariam, Franciscj Plowden, Armig. gnatam, e quâ prolem binam, sed in cunabulis extinctum suscepit, Gervasium scilicet et Mariam; sororem habuit unicam, Annam Rob’. Thorald, Armig. nuptam, sine exitu defunctam, 26 Junij, 1624, obijt, et in illo antiqui sui stemmatis Kervillorum nomen, Quam reliquit conjux vitâ, eum sequuta est, consors morte Martij 6to eodem anno.

This, then, was the end of the ancient Kervile line in Wiggenhall St Mary’s. The tomb still exists, even now, but for years it was kept under a plastic tarp to protect it from water damage. The church is a redundant one, to be found with some effort at the end of a long, somewhat lonely rural lane.

As for St Mary’s Hall, having passed through the Gawsell, Berners and Brown families, most of it was demolished at the end of the eighteenth century. It was then partially rebuilt in the mid nineteeth century by an eccentic Australian named Gustavus Helsham. In the early 1980s it was briefly inhabited by the Scottish poet George MacBeth and his wife Lisa St Aubin de Terán, a novelist. Although it featured at the time in some photo shoots (see, eg, Elizabeth Dickson, The Englishwoman’s Bedroom (1985)), I don’t think she enjoyed it much. In her autobiography Off The Rails: Memoirs of a Train Addict (1989) she referred to it thus:

For almost two years I had looked out across the bleak flatlands of the Fens, watching the bare treeless expanses of clay mud peppered only by scattered bungalows and the distant glint of the sugar factory chimney. It seemed ironic that I, who had once been the Queen of the Andes, with my endless miles of sugar-cane and the tallest chimney in the state, should have come to fester in the long shadow of a steel sugar-beet plant.

She never mentioned the Kerviles. The couple soon divorced.

These days, I’m happy to report, St Mary’s Hall seems to be occupied by owners who actually like it, and I am told that the gardens, in particular, are absolutely lovely.

* * *

Back, not a moment too soon, to the subject at hand. Thomas Moore married Martha Jackson in 1630 at Newton-in-the-Isle, just northwest of Wisbech. They were listed in the parish register as “Thos. Moore gent, and Martha Jacksonn gent”. Harington Boteler was the rector who married them.

It’s just as well to admit that there is a great deal we don’t know, and perhaps can never know, about how this marriage came about.

In 1630, the newly-married couple would have been about 28 years old – perhaps slightly old for a first marriage by the standards of the time. Martha Jackson’s father had been dead for about ten years. Given the legal disputes that had dogged her family, her dowry might have been a bit speculative. Her mother, Martha Jackson née Lawrence, was still alive at the time. And, as we have seen, Thomas Moore the elder had died only a couple of years before, leaving his son as executor and chief beneficiary of his will.

We know from what happened later that Thomas Moore, son of a yeoman farmer, had by this point somehow become a solicitor. For this to be the case, I think he must have gained admission to one of the Inns of Chancery, where he would have been receiving a specialised training in the law before becoming a solicitor in his own right. How this happened, though, is anyone’s guess.

Was he at Cambridge first? If so, I have seen no evidence for this. Meanwhile there are few surviving admissions registers for any of the Inns of Chancery, and even these are not easy to consult. We can perhaps assume, though, that he would have spent at least a few years in London. Did he then return home to practice law in King’s Lynn?

In some sense Thomas Moore’s pursuit of a legal career is unsurprising. The study of law had long been a means by which bright young men from unremarkable families had been able to make a name, and sometimes even a fortune, for themselves. Bacon, Gawdy, Coke — all these familar Norfolk families had benefited from legal careers in a county where litigating against neighbours sometimes felt as much like a sport or pastime as it was a practical necessity.

In 1624 Thomas Moore the elder was the defendant in a legal dispute over property in Wiggenhall St Germans; the plaintiff, John Raynes, was a neighbour and, possibly, a beneficiary of the will of Thomas Moore the younger. Perhaps even for an ordinary yeoman farmer it was helpful to have a lawyer in the family. Still, in an age where patronage powered everything, it would be interesting to know whether Thomas Moore was guided into the legal profession by some powerful family contact.

At any rate, in 1630, the yeoman farmer’s son, now styled “gentleman”, was celebrating his marriage the daughter of an MP and the niece of a baronet. (Young Martha Jackson’s uncle, John Lawrence, was knighted in 1609/10 and made a baronet in 1628.) It seems likely that they soon went to live in Wiggenhall St Germans.

How might they have come to meet? Why might their parents or guardians have thought the alliance a worthwhile one?

The most likely point of contact takes us back, oddly enough, to Chelsea Old Church and the Lawrence family chapel. One of the most remarkable funerary monuments in this remarkable space is that of Sara Colville, youngest daughter of Thomas Lawrence, hence Martha Jackson’s aunt.

Sara had married Richard Colvile of Newton Hall, just outside Wisbech in Cambridgeshire, in 1613. Despite her long connection with Newton, however, Sara, when she died in 1631, chose to be buried in the family chapel in Chelsea. Here she is shown, a half-figure carved in white alabaster, rising from her black marble coffin, hands raised, the trumpet of doom sounding overhead. This striking, indeed borderline alarming image is accompanied by the following text:

SACRED

to the blessed memory of that

unstayned copy & rare example

of all virtue

SARA

wife to Richard Colvile of Nevton

in the Ile of Ely in the county of

Cambridg Esq daughter to

THOMAS LAURENCE

of Iver in the county of Buckkingham Esq

who in the 40th yeare of her

age received the gloriovs reward

of her constant piety

being the happy Mother of 8 sons

and 2 davghters.Wonder not (reader) how this stone

Should be so smooth & pure: there’s one

That lyes within’t, by whose fayre light

It shines so cleere & looks so bright

The Cutters art could only give

A forme unto’t: no power to live;

Nor shall it ever loose this grace

Till she arise & leave the place;

For losse of whome ye mournfull Urne

Shall fire, and to Cynders turne.

She dyed the 17th of aprill

1631.

The marriage between Martha Jackson and Thomas Moore took place in the year before Sara Colvile’s death. What if, after the death of William Jackson the elder, his widow decided to seek refuge, along with her two children, in the welcoming home of a favourite sister? What if they went to Newton?

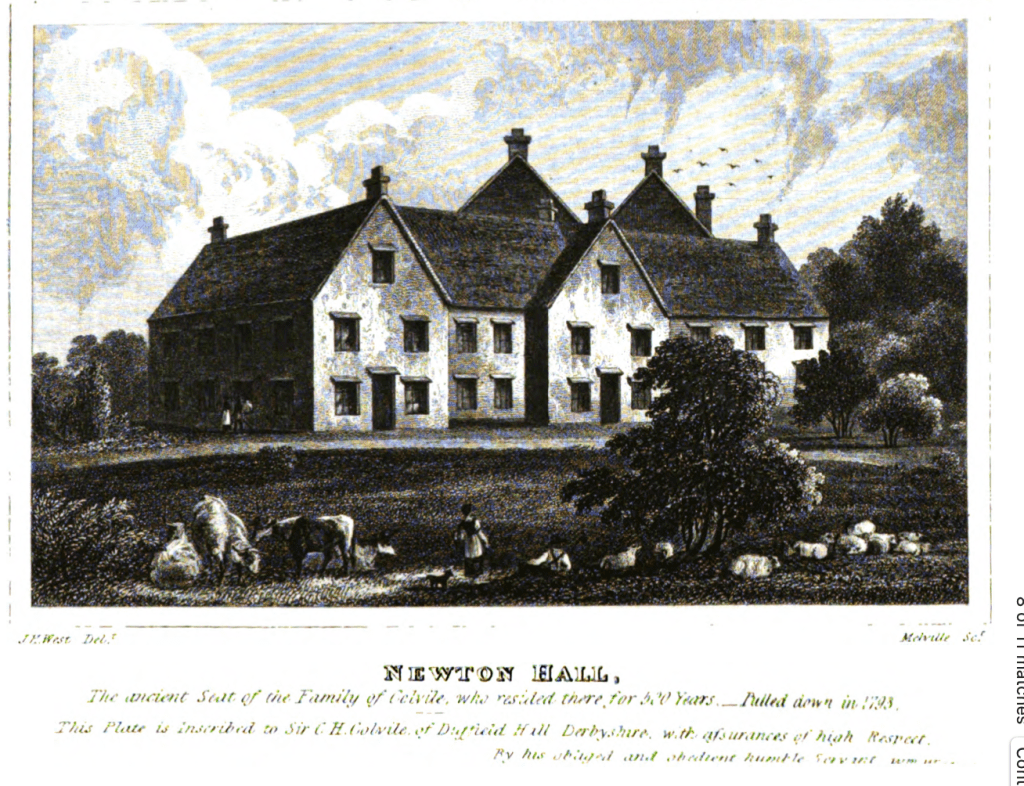

Newton (often called “Newton in the Isle” to distinguish it from other Newtons) was, after all, only about sixteen miles by road from Wiggenhall St Germans. It’s a place where the name gives away everything about its history, a “new town” coaxed into existence as late as the 13th century by purposeful drainage schemes, possibly organised by the Benedictine monks of Ely. Almost from the start, the village had been dominated by the Colville family. Newton-based Colvilles had fought at Crécy and Agincourt, then come home to be commemorated in the parish church. Their base was at Newton Hall, and they lived there for over 500 years.

Sir Thomas Colvile (knighted 1611) had died in 1611, leaving no son and no will, at which point his brother Richard succeeded. The family knew some tragedy — their eldest son having died in a freak riding accident in 1622 at the age of seven years. But they kept a large and generous house. Perhaps young Martha and her brother William spent much of their early adulthood here. Is that how the family came to know Thomas Moore?

But there’s also one further possible link. Oddly enough, the surname Jackson — Martha’s father’s name — also pops up amongst the gentry-level landowners in Newton and nearby Walsoken. For instance, near the west end of the churchyard of St James in Newton is an old house, formerly the property of one Robert Jackson, who succeeded to it on the death of his mother Margaret in about 1659, that later came to be called the Lumpkin House. Might there have been a connection between these Jacksons and Martha Jackson’s own father?

We know, incidentally, nothing at all about William Jackson, Martha Jackson’s brother. Someone of this name was admitted to Christ’s College, Cambridge in March, 1624/5; his father was listed as William Jackson “of Kent”, which fits the facts less well than Surrey might have done. This William Jackson took his BA in 1628/9. Again, though, Cambridge is at least near Newton.

So perhaps Thomas Moore came to the attention of the Jacksons via the Colvilles. The counter-argument, I suppose, would be that while Marshland is quite close to the Isle of Ely, it lies in Norfolk, which was an a different judicial circuit than Newton. Did sport — hunting, hawking — transcend these boundaries? Or were there social links we cannot now detect? Or was it something else altogether.

There’s a strange coincidence, by the way, in the fact that the most southern part of Newton is called Fitton End. As we shall see, Fitton is also a name strongly associated with Wiggenhall St Germans and an important medieval manor there, albeit one that had shrunk slightly in significance by the 17th century. Having been owned first by the Fitton family, then in the 13th-14th centuries by the associated de Wiggenhall family, the manor of Fitton then ended up in the hands of the Howards who were to become dukes of Norfolk. Their interests moved elsewhere, so that in 1566 it was owned by Richard Everard, who bequeathed it to his son John.The Fitton estate along with 164 acres of land, mainly in Wiggenhall St German but including property in the other Wiggenhall parishes, was purchased by the Corporation of King’s Lynn from John Everard’s heirs in 1612. Was there some kind of connection, then, between the Corporation, St Germans and Newton, perhaps relating to the extensive draining programme that took place in the latter in the mid to late 17th century?

Perhaps we shall never know. In any event, however they met, in 1632 a child was born to Martha Jackson and Thomas Moore. She was a girl. Like her mother, grandmother and great grandmother, she was named Martha.

* * *

In due course, Thomas Moore and his wife produced a second child — another daughter. She was called Dorothy, presumably in honour of her paternal grandmother. The Moores would have no more surviving children.

I assume that Thomas and Martha Moore lived at Wiggenhall St Germans. Where exactly, though, did they live?

As we have seen, by the early seventeenth century, the most important house in the area was at Wiggenhall St Mary’s, where the Kervile dynasty had, as of 1624, given way to their distant relations, the Berners family. As for St Germans itself — more of a “first among equals” place, given its relationship with Lynn — there were perhaps only three potential houses of any consequence there.

The oldest of these was probably Fittons, seat of the manor which had, in earlier times, encompassed most of what are now the Wiggenhall parishes — the manor discussed above. It was here, at place called Fitton Oak, where at least by legend the hundred court had once been kept; it was here, verifiably, that the Howard family, latterly dukes of Norfolk, had got their start. The Elizabethan house with its stepped brick gables still stands, albeit much-modified and now serving as a tile warehouse. “Interior of no interest except for hollow moulded beam in lounge inscribed T 1570 W” claimed the author of the 1984-vintage listing notes, discouragingly.

In the 18th century, the Pattricke family were living at Fittons, so it’s conceivable that they were there in the seventeenth century as well, perhaps leasing the property from the Corporation of Lynn. As we shall see, they were a family well known to the Moores.

Another possibility is the St Germans Hall, on the east bank of the Great Ouse, facing the river. According to the official listing the house, now Grade II* listed, seems to have been built in the mid 17th century, and then altered in the early 18th century, although it probably stands on the footprint of an older building. Further additions were made in the late 19th and the 20th centuries. It is built of brick with a tiled roof, on an H-shaped plan. Old photos circa 1900 show what looks like a parlour with 17th century oak panelling. Elegant, well-kept and very private, St Germans Hall sits quietly behind its wall, cherishing its secrets.

As far as I can see, the only other building in St Germans of relevant age is White Hall, on the west bank of the Great Ouse, facing the church. Although apparently quite modest and rather alarmingly, wholly unlisted, recent work has shown that the house has in fact two brick fireplaces and oak panelling all of which date back to the start of the 17th century, if not earlier — as well as other work from the early 18th, 19th and indeed 20th centuries. Why “White Hall”? Possibly the brick would have been rendered and whitened, like the beautiful south-facing porch at the church of Wiggenhall St Germans, built circa 1500. In the 18th century the property had a reasonable acreage associated with it, and although it looks fairly humble now, in the late 16th century, its brick construction would have been an indicator of relative wealth and prestige. Might this have been Thomas Moore the elder’s farmhouse, gentrified a bit over time? Or is St German’s Hall, despite its rather late date, the better option?

Until further evidence comes to light, given the amount of change that has taken place in all these houses, we may never be certain where in St Germans Mr and Mrs Moore actually lived.

* * *

St Germans lies only a short distance south of King’s Lynn, connected to that once-thriving port both by road leading up through Setchey and West Winch, and by river itself. In the Moores’ time, the bridge that links the two halves of the village was the northern-most bridge across the Great Ouse. After that, there was only the Lynn ferry, and then the open sea.

The village was and is always a good deal more than a sort of commuting suburb of the nearby port, but at the same time, that proximity meant that St Germans had a connection with Lynn unique amongst the villages and hamlets of the Marshland. As we have seen, the Corporation of Lynn owned property in St Germans and there were often family and commercial ties between the two places. The river and the port, in turn, connected St Germans with the wider world beyond. It’s worth insisting on this point, if only because the village can sometimes seem, in the most delightful way, like a tranquil backwater. In the early modern period, however, it was nothing of the kind.

It was also a place in transition. Marshland had been the subject of drainage projects ever since the time of the Romans, if not before. The “Roman Bank” the formed the eastern boundary at Newton may well have been exactly that. Yet the period in which the Moores were living at St Germans saw what the greatest changes in the area in recorded times.

From the 1630 through into the 1650s, various commercial syndicates contracted with the Crown (or, during the Interregnum, with Parliament) to drain the vast fens that lay inland from the Wash, embanking the broad rivers, changing their rate of flow, and creating huge new tracts of dry, arable land. Investors were delighted; local people, their way of life for millennia having been predicated on free access to the abundant natural resources of the marsh and fenland environment, were forced back upon protest, riot and sabotage.

Perhaps more relevant to Thomas Moore, the drainage schemes also generated a vast number of legal disputes. Certainly, the whole matter of embanking, draining and flood control was one on which everyone in the Marshland had an opinion. A pamphlet by Moore’s neighbour Hatton Berners gives an example of this — perhaps we can detect in it the tone of countless conversations taking place by the side of smoking fires in ramshackle hovels just as often as they did in oak-panelled, book-strewn, elegant rooms.

That, though, was only a symptom of a more general social and political instability. The years of the Moores’ married life could hardly have been more tumultuous. Although Norfolk was under Parliamentarian control from the start of the Civil War — hence the lazy assumption in some quarters that it was solidly Roundhead — there were still many people in the county, especially well away from Norwich, who supported the King’s cause. In particular, the gentry in the west of Norfolk tended to be Royalists.

Once the Civil War began, St Germans once again occupied a position of tactical significance, sitting as it did on the northernmost bridge connecting the east of England with the Midlands and the North. The summer of 1643 in particular saw an outburst of local conflict, as the inhabitants of places like Crowland and, indeed, Lynn itself, declared for the King, only to end up besieged by Parliamentarian forces. There is a very good account of the conflict within King’s Lynn here.

The prologue to the siege took place in the spring of 1643, when Sir Hamon L’Estrange of Hunstanton (1605–1660) — a learned, godly, self-assured, eccentric, rather elderly Royalist — began, not very secretly, to organise resistance against Parliament within Lynn. On 20 March, Col. Oliver Cromwell was forced to rush to the town to take control of affairs. But on 8 May, when the burgesses of the town received Parliamentary orders to arrest seditious figures such as Sir Hamon himself, they refused to obey. Matters came to a head on 13 August when, as the Earl of Manchester’s forces drew ever nearer to the town, the mayor of Lynn ordered the house-arrest of Parliamentarian councillors, proclaimed Sir Hamon governor of Lynn.

Parliament lost no time in responding. Not least, if the Royalists were to hold Lynn, access to arms from Continental Europe would be a major boost to their cause. So all attention turned to retaking Lynn.

Capt William Poe, in charge of a detachment of troops from Essex, blockaded roads and bridges leading into the town. Meanwhile the Earl of Manchester and Col Oliver Cromwell set up artillery on the west shore of the river Ouse, allowing them to bombard the town’s commercially important waterfront.

The Eastern Association hoped to field 4,000 horse and 7,000 foot soldiers. The Royalists in the town, for their part, had probably hoped that the King’s army, then in Lincolnshire, would come to relieve them, or that the Earl of Newcastle would travel down from Hull long enough to render them some sort of aid.

Neither, however, occurred. After a five-week seige, the town surrendered on 16 September. Unsurprisingly, Parliament demanded enormous sums by way of punitive reparations. Lynn ended up as a garrison town for the rest of the war, with all the costs, annoyances and lurking resentment that entailed. The town’s new governor — who remained in place until the Restoration, which is to say, for the next seventeen years — was Col Valentine Walton. He was Cromwell’s brother-in-law, a puritan and, in due course, a leading regicide. From 1644 to 1651 the recorder of King’s Lynn (ie the officer responsible for keeping its legal records) was Miles Corbet, anther puritan who was to sign the King’s death warrant. The town’s administration was, in short, under Roundhead control for much of the Moores’ adult lives, just as the Church of England suffered continued assault from puritans, presbyterians and other sectaries.

I can’t believe that the bridge at St Germans wasn’t under permanent guard, or that there wasn’t a sustained and intrusive military presence in the village, perhaps with troops quartered in private homes. The Moore daughters must have grown up under a sort of semi-benign occupation.

It must have been hard for their parents, too. It’s easy to forget what an impact these changes would have had on those who, unlike present-day readers, didn’t know that the Restoration would occur in 1660. It’s easy to skim past those seventeen years as if they didn’t make much difference.

The siege of Lynn was not a particularly bloody affair. Buildings were damaged and in some cases destroyed, but the number of lives lost probably numbered in the dozens at most. Still, to say that it was not exactly Marston Moor misses the point of what it actually was: a moment where a place like St Germans was suddenly thrust near to the centre of national affairs, where neighbours and even kinsmen showed themselves potentially willing to kill each other, where wounds were opened that might never actually heal.

* * *

The war, incidentally, almost came to Lynn a second time. In April 1646, with all his armies defeated in the field, the beleaguered King hatched a scheme to escape from Oxford towards King’s Lynn, where he hoped “if it be possible, to make such a strength, as to procure honourable and safe conduct from the rebels” — or, failing that, to travel by sea to Scotland, or indeed Ireland, France or Denmark. This was not, unfortunately, a very plausible scheme. Although there were surely still Royalists in the Lynn hinterland, they were, after the siege of Lynn, watched very closely.

Nevertheless in 26 April the King, having disguised himself as a servant, set out from Oxford with two loyal companions. They went first to Hillingdon, where the King parted company with one of his attendants, then set off towards Downham Market. There, on the night of 29-30 April, King Charles lodged at the White Swan, less than ten miles by road south of St Germans. The White Swan still exists, by the way, albeit very much rebuilt, as does as street called “King’s Walk”, said to mark the place where the beleaguered monarch passed the time by strolling back and forth as he waited for news about the Scots.

From Downham Market the King went on to the hamlet of Crimplesham, and thence to the little village of Mundford. He couldn’t do much until he had heard back from various agents he had sent to parley with the Scots about the terms on which he might entrust himself to them. At Mundford, however, the King learned that news books had arrived in Norfolk, reporting on his flight from Oxford. This, surely, made matters much more difficult, as he was far more likely to be recognised.

I am not sure, by the way, where he stayed in Mundford. The hotel now known as the Crown, perched on the edge of an attractive village green, claims to date only from 1652. There are claims that he stayed in a very modest little house now called Rosemary Cottage at 2 West Hall Road. They may be correct.

From there, the King was to travel onward for just a few more days: into the Isle of Ely, then down to what was left of Nicholas Ferrar’s religious community at Little Gidding (the Norfolk historian Robert Ketton-Cremer’s account of this visit is as powerful as anything he ever wrote), to Crimplesham, then back up through Stamford and Southwell. Those were the doomed King’s last days of freedom, riding through his beautiful countryside in late April and early May. Everything that happened afterward would be sadder and more devoid of hope.

It’s not impossible, along this route, that King Charles might have encountered people known to Thomas and Martha Moore. Not least, those who were later questioned about his journey were often, for obvious reasons, vague about whom he’d met along the way, let alone who had lodged him or otherwise offered their sovereign assistance. In particular, I sometimes wonder what route he took across the Isle of Ely, and whether he went anywhere near Newton Hall. We shall see later that some in the area demonstrated their loyalty throughout the Interregnum, and were very nearly recognised for it, too.

The country must have talked of little else, albeit in hushed voices, for many months afterwards.

* * *

We are in King’s Lynn, near the Saturday market, looking at a long, low building covered in strangely-chequered flintwork. Fom the late fifteenth century up until the Reformation, this was the meeting place of the prestigious, ultra-wealthy Guild of the Holy and Undivided Trinity. Afterwards, it was simply the Guildhall. This is where the Corporation of King’s Lynn — the mayor, burgesses and other concerned citizens — met to discuss the issues of the day.

At their meeting in July 1651, the mayor and burgesses of King’s Lynn selected “Mr Moore” — they don’t seem to have been sure of his first name — to serve as town solicitor for one year. For this he was to be paid £6 13s. 4d. He was mandated to work with the town recorder toward the goal of advancing the town’s business in London, particularly before the Council of Trade, a predecessor committee to the Board of Trade. All the town’s “charters and other writings” were to be left in his custody. And, indeed, Thomas Moore is mentioned afterwards in the accounts as being “our town’s solicitor at London”, as if he spent much of his time there.

In practice, I think this job would have involved not only carrying out actual legal work for the corporation, but also what we would now consider lobbying — promoting the interests of Lynn when it came to issues of taxation, regulation and commercial opportunities. Some of the work would have been formal, but much of it must have been informal. Trying to catch the eye of some person of influence, perhaps to have a private word in a quiet corner, to send a gift that would guarantee some slight degree of good will, to be first to hear the gossip and pass it on to someone who might appreciate it — surely all this was part of what Thomas Moore was being asked to do in London.

This is part of why I think Thomas Moore must have been a gregarious, convivial soul, always up for a drink and some gossip — the more scurrilous, the better. Anyone who has ever spent much time in politics will know exactly the sort of person I mean.

In 1651, when Thomas Moore was town solicitor, the recorder of Lynn, who was supposed to be in contact with him in London, was Guybon Goddard (1612-1677), latterly of Flitcham. He was MP for King’s Lynn 1654-59 and Castle Rising in 1659, where he earned the gratitude of posterity through his decision to keep a sort of diary. He had been deputy recorder to Miles Corbett from 1645 until January 1650 when he took over. A lawyer as well as an antiquary with a particular interest in Norfolk, Sir William Dugdale was his brother in law. Sadly, his collection of antiquities and his writings, praised by Dugdale, Blomefield and Parkin, were never published and were lost after his death in 1677. Thomas Moore must have worked closely with him.

What I don’t know, yet, is whether Moore continued to work for the corporation in this role after 1651, although as the corporation’s records survive in very good order, I’m sure that an answer can be found.

* * *

A few years before Moore’s appointment, in 1646, there was a major witch scare in King’s Lynn.

In May 1646 the Corporation of King’s Lynn invited Matthew Hopkins to the town, specifically to purge the place of witches. Why that was thought necessary is less clear. Over the preceding year or two, Hopkins had developed a reputation for his witch-finding skills, so perhaps this was simply an amenity that all the most up-to-date East Anglian towns hoped to secure for themselves and their citizens.

In any event, Hopkins — who was probably already suffering from the tuberculosis that would kill him just over a year later — arrived in the town, made his enquiries, and duly identified eight people as witches. Two of these — Dorothy Lee and Grace Wright — were hanged that year. Five others were acquitted, while one woman was dismissed as not being of sound mind. In 1650, after Hopkins had gone to his reward, another Lynn woman — Dorothy Floyd — was also hanged for witchcraft.

The records of the Corporation show that Hopkins, who might or might not have started life as a lawyer, was paid at least £20 for a few weeks of work — considerably more the town solicitor as offered.

* * *

Back in London, Sir John Lawrence, knight and baronet — and also Martha Moore’s brother — had died in 1638.

Unsurprisingly, he was given a handsome marble funerary monument in Old Church, Chelsea. It bears the following inscription:

Sacred to the memory

Of Sir JOHN LAURENCE late of Iver in ye county

of Bucks Knight & Baronet who married GRISSELL

daughter & coheire of GERVASE GIBBON of Benenden

in the county of Kent Esq. by whom he had issue

seven sons and foure daughters. Hee deceased the

XIIth of November 1638 aged 50 yeares.

When bad men dy & tyrne to their last sleepe

What stir the Poets and ingravers keepe

By a fain’d skill, to pile them up a name

With termes of Good & just, out lasting fame

Alas poore men, such have most neede of stone

And Epitaphs, The good (indeed) lack none

Their own true worth’s enough to give a glory

Unto th’ uncankerd Records of theire story

Such was the man lyes heere yet doth pertake

Of Verse and Stone but ’tis for fashon sake.

It’s rather ironic that the message of Sir John Lawrence’s own memorial is that lavish memorials are, themselves, entirely unnecessary, undertaken only “for fashion’s sake”, and that the good have no need of such nonsense.

He was succeeded by his son, another Sir John Lawrence, second baronet, aged at the time 28 years.

Did Martha Moore ever come to London with her husband, or did she stay in Norfolk with her daughters? Did Thomas Moore spend time with his well-connected Lawrence cousins-by-marriage? How well did they know Chelsea Old Church, and the increasingly grand little family necropolis that the Lawrences had made for themselves there?

* * *

We are now back at St Germans, next to the parish church, where the garlic-mustard and cow parsley up near the bank is all in bloom.

It was in this church, on 27 April of 1649 — less than four months after King Charles’s execution — that Thomas and Martha Moore’s eldest daughter, Martha, was joined in marriage with Robert Appleton.

The record of the marriage kept by Gray’s Inn states that Robert Appleton was a bachelor, aged 28, and a member of Gray’s Inn. Young Martha Moore, for her part, was 17 years old. Thomas Moore, by the way, is styled “gentleman” of “Germaines, co. Norfolk”. Both Thomas Moore and his wife would have been about 46 years old at the time.

As it happens, we know a bit more about Robert Appleton. Born in 1620, he was the son of John Appleton and Frances Crane, of Chilton Hall in Suffolk. They were a family of wealthy clothiers, mildly puritan in religious cast, well-connected in church and legal circles as well as mercantile ones. In 1631, however, John Appleton died, leaving his estate to Robert, who was only eleven years old at the time.

Robert was admitted to Gray’s Inn on 13 November 1638, and called to the Bar in 1641 — only on the provision, though, that he had not “been in any service against the Parliament”. Much later, he was to be the indirect beneficiary of bequests by his uncle Robert Ryece of Preston (d 1638), an important Suffolk antiquary. Rightly or wrongly, he gives the impression of being a cultured, thoughtful person, with very good manners and an undisguised interest in the world all around him.

As a barrister from a well-established gentry family, Robert Appleton was a good match for Thomas Moore’s eldest daughter. Perhaps it’s not too frivolous to imagine the wedding party making their way back from the church: the bride’s father, jovial and transparently delighted, exchanging legal gossip with his polite new son-in-law; the bride’s mother, pleased to be reunited with her Colville relations who had been invited to celebrate the occasion; the bride herself, basking in the attention but perhaps also a bit apprehensive about her new role in life; and of course young Dorothy, the bride’s little sister, wondering whether someday she, too, would secure her own well-connected barrister.

Given the date, we can only speculate about the rite through which Robert and Martha were married. Did they use some sort of reformed service, as suggested by the Directory for Public Worship, or did all these lawyers manage to get away with clandestine use of the outlawed Book of Common Prayer? Although the Richard Aylmer who was licenced in the parish as a preacher turns up again as the vicar in the 1660s, it’s unclear whether he was, like so many clergymen, ejected from his living for at least some of the intervening years. This being the case, it’s hard to know what the Moores, their friends and relations could have got away with doing by way of a wedding celebration, so close to King’s Lynn, its spies and its hard-line puritan administration.

* * *

We do, as it happens, know a little about Robert Appleton, although to discuss this, we’ll need to go back in time slightly further. During his years as a pupil at Gray’s Inn, in the late 1630s and early 1640s, he wrote various letters to his cousin Isaac Appleton, three of which survive, each of them conveying news about current affairs.

Although news books — those sometimes eccentric, often unreliable distant ancestors of our present-day professional journalism — already existed, many people still relied on personal contacts in London for prompt, reliable insights as to what was happening there. “Sir, I am ready to serve you with my penn, when there is any newes stirring here at London,” wrote Robert to his cousin, confident that this offer would be welcomed.

We, in turn, are fortunate that Robert Appleton’s letters home were preserved amongst the Tanner papers, now in the Bodleian Library, and also perhaps fortunate also that the numerous American descendants of Samuel Appleton, emigrant to New England, have shown such beneficial interest in them.

The letters tell us quite a lot, not just about the news, but about young Robert Appleton, too. Writing to his first cousin Isaac (i.e. the son of his father John’s elder brother Sir Isaac), Robert is deferential, extremely courteous, transparently trying to make a good impression, sometimes stilted and pretentious in his language although slightly more smooth as the years go by.

In his first surviving latter (15 February 1639) he describes how “one Mr Oberson schoolemaster of Westminster”, having written to the Bishop of Lincoln describing Archbishop Laud as “litle grace, litle urchine, and little hocus”, was fined £5,000 and sentenced to have one of his ears nailed to the pillory in Westminster Yard, then to be removed into Deanery Yard before his school where he was to have his other ear nailed to a pillory, and then to be imprisoned.

What madness is it for men to use their pens in such a manner? Your sage Apothogmes shall make me shunne all such extreames, and avoid all such Catechreses, wherin I see much folly but no piety.

Here speaks the voice of what I think was probably a moderate, pragmatic puritanism current amongst the Appletons and their circle — with young Robert keen to demonstrate that he’s on the same page here as senior members of his family.

By the time Robert wrote his next surviving letter, however (4 June 1641) matters had moved along quite rapidly. At this point, Robert gives his uncle a full, if rather breathless report of parliamentary business in particular: Archbishop Laud is to be tried for treason before the end of the judicial term; parliament is worried about raising funds for the army; a bill has been passed against pluralities for churchmen, and indeed there were rumours of a bill to do away “root and branch” with bishops, but this had been postponed. There were also rumours that the King was to go to Scotland — “his provision & trunkes are already gone” — also “the Prince [Rupert?] lately broake his arm, but he is now well, & this weeke was made governour of the artillery”.

All of this, I should stress, occurs alongside much chat about family business: the sale of some hops, some “patterns” sent up to Suffolk. But always, the letters circle back round to the epochal political developments that Robert so clearly realised were happening all around him.

“I have some new bookes and speeches about the matters now in question, which I intend to bring down to Holbrooke with me the latter end of next week,” he promises enticingly. We may imagine, then, young Robert sitting down with his cousin — perhaps with his uncle too, and with other Suffolk gentlemen — in a context where his direct access to the latest London news might accord him respect and authority out of all proportion to his relatively junior status. At other times, though, as in his third and final surviving letter, he shows a preference for sending news via another close relative, for instance Sir Robert Crane. Perhaps, as the situation deteriorated, there were some things that it was more politic not to consign to the written page?

Writing on 23 June 1641, Robert continues his political report. The most exciting portion of this is the story of a literal fight that broke out in a parliamentary committee:

Last Saterday there was a controversy between the Lord Chamberlayne [ie the Earl of Essex] & the Lord Matravers [ie Henry Frederick Howard, Lord Maltravers]: the Lord Matravers gave my Lord Chamberlayne the lye, whereupon he strucke Matravers over the head with his staffe: Then the Lord Matravers tooke up a standish & threw at the Lord Chamberlayne: this moved so great a stirre that the Committee did rise: complaynt was made to his Majesty, & on Monday the upper house committed them both to the Tower.

A “standish”, in case you were wondering, is a stand for holding pens, ink and other writing materials. Robert then interrupts himself, remembering he’ll be in Suffolk himself soon:

I must goe noe farther, I am too much forgetfull; Excuse me Sir, I had rather have the truth of my newes questioned, then your expectations of newes upon Saturday at night should be frustrated. It is Mr Lambert’s Motto the newes decies repetita placebit, & it shall be my resolution ever to be servicable to my friendes.

So it is that the letter returns to the subject of hops, Robert’s intention to buy “a chamber which is over me; it is a very litle one, but shall content me”. He sends along some vervells (rings for the leg of a hawk) — did the cousins go hawking together?

The youthful law student was clearly looking forward to being back in Suffolk. The reason why soon becomes clear:

The heat of the weather & the spreading of infections make me to retyre in: there died this weeke of the poxe fourscoare & eight, and 56 of the plague. Bankes his house at Chancery lane is shutt up, & his wife is dead of the plague: there are foure houses at least in Holborne visited; 10 died this week of the plague in the parish. I keep myselfe to my chamber, Greyes Inn Hall & the Walks.

As we know, however, Robert Appleton survived the plague, and lived to be married more or less a decade later.

If this all seems like a digression — which in some ways, of course, it is — I remain unapologetic. There are so many voices from the past that we’ll never hear. Although these three letters aren’t much, they at least bring the young law student Robert Appleton alive for a moment — his excitement, his enthusiasm in sharing the news about them, tempered perhaps with a touch of homesickness for his family and friends in Suffolk. And then there’s the insight into a season of pox and plague apparently so minor, by historical standards, that it doesn’t even make most mainstream lists. This, too, was the world in which Martha Moore must have lived.

* * *

A year or two after they were married — which is to say, in about 1651 — Robert Appleton and his wife were blessed with a child. Yes, they named their new little daughter Martha. One hopes that Martha Moore was pleased with this.

On 10 October 1653, however, disaster struck. Martha Appleton died, aged only 21 years.

Was Martha in St Germans when she died? She was certainly buried there. Her mural monument survives, at the east end of the north aisle of St German’s church. Here is her inscription:

Here lyeth vertuous child, wife and mother

Matchless all in her save each to other

Here careful Dorcas lies; or if not shee

Then tell me, Reader, whose those webbs should bee.

Oh, here’s that Pelycan, which did not spare

To nurse her tender young with her heart [sic] blood

Here lies a Phaenix whose productions rare

Of grace, invited others to bee good.

Hold this was worthy prayse, unto her life

Shee was a lovinge, prudent, faythfull wife

Who needed neither stone nor grave nor cheast

That lyes intombed in her Father’s breast.

Who put on Immortallitye

in the year of her

Pilgrimage 21

upon the [year of her] Redeemer

10th of October 1653

Aboute the upper end of this chancell

lyeth the body of Mrs Martha Appleton, eldest

daughter and coheyre unto Mr Thomas Moore

and Martha his wife of this Parrish (the daughter

& Heyre of that truly religious Mrs Martha

Jackson, who also lyteth interred within

this chancell)

To whose most beloved and pious

memory her saddest husband

Robert Appleton Esq

Procured this Monument

To be erected.

For to me to live is Christ

and to die is gaine Phil: 1, 21.

[“Webbes”, I think, mean sheets of lead in which the dead were enclosed, prior to being placed in their coffins.]

Painted onto the marble of the mural monument, according to the antiquary the Rev Mr Parkin, were the arms of Appleton, argent, a fess ingrailed, sable, between three apples leafed, vert, impaling Moor, sable, a swan, argent, in a bordure ingrailed, or. These arms have, sadly, long since worn away. Part of the monument is cracked, and I think it must have been moved from the chancel to its present spot in some later reordering of the space. Still, it remains perhaps the most elegant monument inside the church.

This may well be the only accessible record of Thomas Moore’s coat of arms. The College of Heralds will, no doubt, have additional information, but this is difficult to obtain. It seems likely that Moore was granted them personally as his father was, as we have seen, a yeoman. Sable — black — is probably a punning reference to “Moor”, while the swan may well represent Moore’s aspirations as a poet — something about which we’ll hear more soon.

One might be pardoned, in any event, for thinking that this was enough of a monument to 21-year old Martha Appleton. In the chancel, however, next to the high altar, there is an additional tomb slab. This is engraved as follows:

Sacred to the Memory of

Martha Appleton,

Daughter of Mr Thomas Moore

of this Parrish, who dyed

the 10th of October 1653

Harke, under this sadd stone doth lye,

My dearest childs mortalitie;

The rest was such as could not dye,

But triumphs to Eternitie.

Perticulers should I rehearse,

They’d load a stone, and straine a verse;

Her Mortall Parents else could make,

Her Fame Immortall stories to speake.

But yet since shee did never care

For such vaine Toyes, I shall forebeare,

And now in Glory let her rest

Which she did ever Valew best.

Close by, at whose right breast doth lye

Her youngest daughter Dorothy

Step’t but to Immortalitye.

Thus it is that we see spelled out what the pelican reference above only suggested — that Martha Appleton died giving birth to her second child — Dorothy, named after her sister, and after her paternal grandmother.

The mural monument was commissioned by Robert Appleton, the grave slab by Thomas Moore. One could probably make too much of the differences of emphasis here. Across the centuries, the shock and sadness of these two men seems more than formulaic, and that is the main thing that comes across in both.

Still, it’s striking that while the grieving father mentioned the little granddaughter whose time here was so very short, the grieving widower refers, with some emphasis, to his late wife’s mother, “that truly religious Mrs Martha Jackson, who also lyteth interred within this chancell”. What is going on here? Was the lack of any other monument to Mrs Jackson a vexed point within the family? Was “truly religious” meant to imply that someone else in this story was only superficially religious?

Martha Moore had lost, prior to 1653, her mother. Her brother William had died even earlier — we do not know the date. In 1653, at the age of about 50 years, she then lost her eldest daughter who was only 21 years old, and a little baby grandchild too.

Her husband may have spent much of his time in London, engaging with the Lord Protector’s administration on behalf of the puritan-run town of King’s Lynn. She may or may not have enjoyed this as much as he did.

It is proverbially impossible to be certain what is going on in other people’s lives, but there are points where we can at least hazard guess. Surely, whatever consolations and entertainments her days might have offered, this cannot have been the easiest of times for Martha Moore.

* * *

Shortly before 1660 — which is to say, right at the end of the Interregnum — Dorothy Moore, the surviving daughter of Thomas and Martha Moore, married Robert Wright, graduate of Cambridge member of Lincoln’s Inn and an up-and-coming force on the Norfolk legal circuit. He must have been something like 25 years old. Dorothy’s age is unknown.

Wright was the son of Jeremy and Anne Wright of Wangford in Suffolk. The Wright family also had deep roots in Kilverstone in Norfolk. Robert Wright was admitted to Peterhouse (not, as some sources have it, Caius College) in 1651, moving on to Lincoln’s Inn in 1654. A colleague described him as “a comely person, airy and nourishing both in his habits and way of living,” and a surviving portrait of him does indeed make him look rather dashing.

Unfortunately, however, he was a terrible lawyer — disorganised, extravagant, and indeed borderline fraudulent in his personal dealings.

We don’t know where Dorothy Moore and Robert Wright were married, but perhaps it was back at St Germans church again, a few feet away from the grave of her sister Martha Wright.

We do, however, know where Dorothy Wright was buried when she died in 1662, only two and a half years after she was married. Like her sister, she was interred at the church in St Germans.

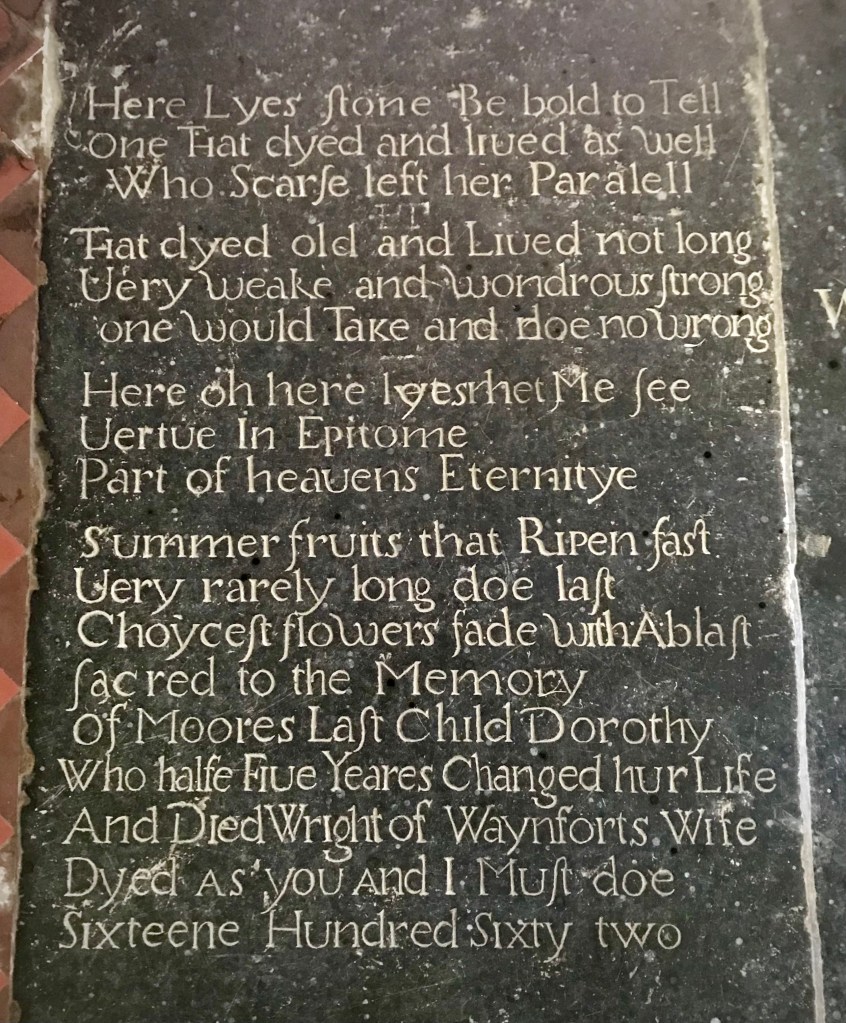

Her funerary slab still survives. Here is the inscription on her stone:

Here Lyes Stone Be bold to Tell

One that dyed and lived as well

Who scarce left her Paralell

That died old and Lived not long

Very weak and wondrous strong

one would Take and doe no wrong

Here oh here [lyes let?] Me see

Vertue in Epitome

Part of heavens Eternitye

Summers fruits that Ripen fast

Very rarely long doe last

Choycest flowers fade with Ablast

Sacred to the Memory

of Moores Last Child Dorothy

Who halfe Five Yeares Changed hur Life

And Died Wright of Waynforts Wife

Dyed as you and I Must doe

Sixteen Hundred Sixty two

Did Dorothy Wright once have a mural monument as well? Or was there a plan that she would, but it never transpired? It’s not hard to imagine Robert Wright saying that he didn’t have the cash but that he would very soon — that it was the next thing on his list of things to do — how extraordinary, that he was thinking about it just the other day! Yet the stone on the floor is all that remains.

As for the stone slab on the floor of the nave (not even the chancel this time), it is rather crudely carved, with at least two mistakes. There should be a space before “Sacred” and the word or words before “see” are not entirely legible, with letters having been carved over each other.“Wangford” is spelled “Waynfort” and “hur” is a pretty bad stab at spelling “her” even by seventeenth century standards. Further, the verse really only makes any sense if one already knows the people involved — and even then, some of it is still very hard to understand. The language seems to revel in its own obscurity. “Scarce left her parallel”? “That died old and Lived not long / Very weak and wondrous strong / one would Take and doe no wrong”? None of it makes much sense, at least without a context that is, now, unrecoverable.

The one phrase that does ring out — perhaps all the more so, given the opaque quality of everything else here — is that unambigious one: “Moores Last Child Dorothy”. It’s probably pushing this all too far, but one can’t help read the sloppiness of the carving, the semi-incoherence, the indifference to whether the message was legible or not, even the slightly self-centred take on what had happened here, to utter despair on the part of the person who composed those verses.

And that, we know for certain, was Thomas Moore himself.

* * *

Whatever his other achievements in life, the thing for which Thomas Moore came to be remembered was his verse — less, though, for its quality, than for the lack of it.

In his account of St Germans, the clergyman and antiquary Charles Parkin, writing about the Marshland parishes roughly a century after Moore’s death, drew attention to Martha and Dorothy’s funerary inscriptions. Parkin noted that

both their epitaphs are in doggrel verse, by their father Moor, who was so much in love with his Muse, that he made his own last will in verse.

This, frankly, seems a bit harsh — especially in reference to a grieving parent, where a modicum of Christian charity might not go amiss.

Moore’s poems for his daughters’ graves, and his famous rhyming will, surely raise a related question — did Moore write other poetry? And if so, does any of it survive? I expect, writing when he did, that any poems he produced were likely to have been handed round in manuscript form, rather than printed. As such, it’s quite possible they don’t have his name attached to them, or they are given as by “TM”, “Mr Moore” etc. I harbour a dream that someday something along these lines will come to light. Please, everyone, keep an eye out for mid 17th century poems of debatable quality that might have been written by Thomas Moore!

* * *

However unfair he may have been about those memorials, Parkin was, however, broadly correct about Thomas Moore’s will. It did, indeed, achieve a sort of limited fame for its author.

The antiquarian book dealer Samuel Gedge records that

[Thomas Moore’s] will seems to have been a literary curiosity even in the seventeenth century: a version is recorded as having been penned in a letter by Philip Skippon (1641-1691) to the naturalist John Ray (1627-1705)

while the manuscript Samuel Gedge offered for sale contains small differences from the version now in the National Archives (PRO11/327272-3). For the Gedge reference, see p. 16 here.

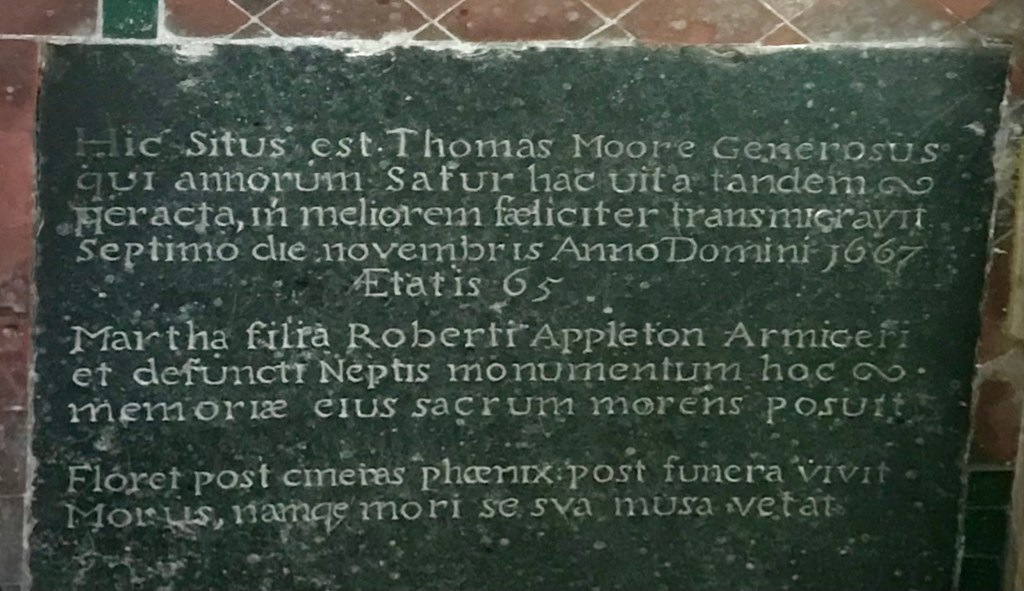

Thomas Moore’s will was written at the end of 1666. This was a year in which Lynn was hit very badly by the plague, something that might perhaps explain the timing. It starts with a verse section, although the latter, more prosaic part is expressed in prose.

In the name of God Amen. I Thomas Moore

the fourth yeare of my age above threescore

Revoking all the wills I made before

make this my last And First I doe implore

Allmighty God into his hands to take

my soule which not alone himself did make

But did redeeme it with the precious bloode

of his Deare Sonne: that tytle still holds good.

I next bequeath my body to the dust

From whence it came which is no more than just

Desiring yet that it bee laid close by

my eldest daughter though I say not why

And leave my Grandchild Martha but her due

my Lands and all my Chattells save a few

You shall hereafter in this Schedule finde

to pyetye or Charitye designed

whome I my Sole Executrix invest

to pay these and my debts and take the rest

But since that shee is under age I pray

Sir Edward Walpole and her ffather may

the Supervisors bee of this my Will

Provided that my Cousin Colville still

and Major Spencely their assistants bee

Foure honest men are more then two or three

And then I shall not Care how soone I dye

if they accept it, and I’ll tell you why

There’s not a man of them but is so just

With whom almost my soule I durst not trust

Provided shee doe make her second sonne

heyre to my house at least and half my land

If shee have such, and when she has soe done

shee be a meanes to let him understand

It is my Wish his name bee written thus

T. A. B. C. or D Moore alius /

Further provisions included the following:

- The parish overseers of the poor at “Germans” as he called it were given £20 “for a stocke to sett the poore on worke”

- The poor of St Germans were also to receive for seven years “one chalder of Coles” to be delivered on the feast of St Thomas, as well as 10s. to the poor of St Marys, and to the poor of St Peter’s and Magdalen 6s. 8d — again, to be delivered on “St Thomas day”.

- Thomas Tudenham “of London” was to receive £20 “he owes upon bond”, “and to each of his children sisters and sister’s children” 40s.